When

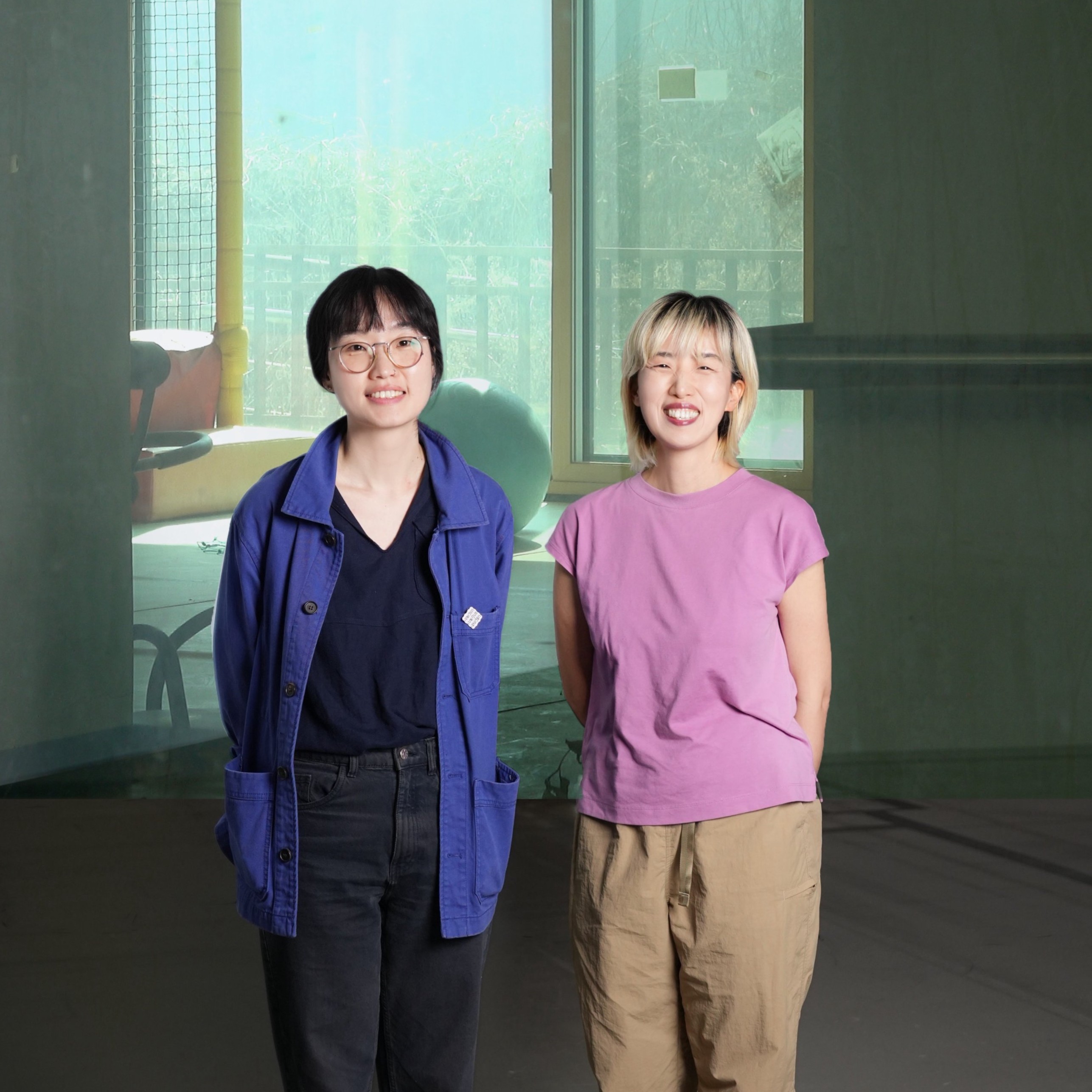

we explain exhibitions, performances, or parades created under the name of dianalab,

people often respond, “So, this is what you call barrier-free, right?” Whenever

that happens, we pause for a moment. Hmm. How should we explain this? Because

we are people who think deeply and react sensitively to the word “barrier,” our

answers are never satisfactory. Sometimes we brush it off with, “It’s similar.”

Other times we deliberately say, “We are not barrier-free, we are

barrier-conscious!”—a concept almost unknown. Either way, it is never something

that can be explained properly in a short time. Where should we begin?

When

we think about the word “barrier-free,” our minds become complicated. The

saddest part is that such conditions are rare in Korea today. Even if we limit

the meaning of barrier-free only to a space without physical thresholds, the

same is true. Through the Discrimination-Free Store project

(Note 1), we came to realize painfully just how difficult it is to find a space

where you can go together with someone who uses a wheelchair, and how dreamlike

it is to hope for a space where you can also stay without discrimination with

other social minorities. That is why the mere sight of the word “barrier-free”

makes us happy, because it makes us think, “Wow! That must be a place where we

can all go together!” Even in Seoul, the city with the most barrier-free spaces

in Korea, the word is by no means common. The reality check that comes with the

boundary of a physical threshold is powerful. And yet, why do we hesitate to

use that word?

First,

it should be noted that within the “we” who do things together under the name

of dianalab, there are people with a wide variety of minority identities. And

within the group of people commonly referred to as “people with disabilities”

or “people with severe disabilities,” there exist vastly different types of

disability and enormous individual differences. It is obvious, but just as not

all women are the same, not all disabled people are similar either. Some people

ask questions like, “What should I do if I encounter a wild bear in the

mountains?” in the same way they ask, “What should I do if I meet someone with

developmental disabilities?” There are even many who ask us to produce manuals

on how to deal with each type of disability.

We,

who are treated as objects to be dealt with, have been thrown out of

restaurants famous for welcoming wheelchair users simply because of having

developmental disabilities (Note 2). On the street, we are glared at, or even

subjected to discrimination and violence from people who themselves are in

marginalized positions. How can we explain this complexity? A physically

barrier-free environment is precious, but it does not guarantee that we will

not be discriminated against. A story about a restaurant owner waiving the bill

out of pity for a disabled customer is not a heartwarming tale.

Eliminating

physical barriers does not make invisible barriers disappear. Nor does removing

a few barriers mean that the others stop operating. We are people with multiple

identities. If it were possible to exist only with a single identity, things

would be simple and nice. But such a thing does not happen in this world. Some

of us are disabled and at the same time women, queer, vegan, parents,

foreigners, people of color, those with low educational backgrounds, and those

living in poverty. Barriers exist everywhere, and they target and penetrate not

only minorities but everyone. Yet, the moment we use the word “barrier-free,”

it sometimes feels as if the world is not like that.

The

reason dianalab does not readily use the word “barrier-free” is that we cannot

rid ourselves of the thought that the moment the word is uttered, we are forced

into a binary framework of thought. Regardless of good intentions and

necessity, saying the word inevitably creates a dualistic opposition: between

those to whom barrier-free applies and those to whom it does not, between those

who invite and those who are invited, between spaces that are not barrier-free

and those that are. Of course, barrier-free as a physical condition is a basic

premise for dianalab to be able to do anything. But the moment we describe

ourselves with that word, it feels as though what we can do has somehow been

reduced. Just as a performance labeled “barrier-free” does not necessarily

guarantee barrier-free conditions for those performing in it. It is difficult

to deny that the utterance of the word itself creates a certain hierarchy.

While

carrying out the Discrimination-Free Store project, we

encountered countless sharp boundaries: “Disabled people are fine, but LGBTQ+

are not.” “Disabled and LGBTQ+ are fine, but it must be a no-kids zone.”

“Animals are not allowed.” “Wheelchairs are fine, but intellectual disabilities

are not.” “Developmental disabilities are fine, but wheelchairs are not

allowed.” “You must call ahead before coming.” “It’s fine as long as customers

don’t see it.” “A guardian must accompany them.” These are just some examples.

The drawing of lines—what is acceptable and what is not—happens everywhere, all

the time. Gender, age, educational level, alignment or misalignment of

biological and social sex, sexual orientation, family structure, race, place of

origin, nationality, religion, class, mother tongue, physical features and body

image, disability status, health… thousands of lines run through us. There is

no place where barriers are not at work. This can even happen within

organizations doing social activism, or among human rights activists

themselves.

One

time, we heard a very striking question: “What should we do if a perpetrator of

sexual violence goes around claiming to be a feminist?” To which someone

answered, “What guarantee is there that someone who calls themselves a feminist

will not commit sexual violence?” It was exactly right. We are fairly cynical

people, so in fact we believe in nothing. We know that people with one minority

identity can very easily neglect or take a very violent attitude toward other

minorities. And unfortunately, such things do actually happen.

Therefore,

we try as much as possible not to hold expectations or prejudices about “XXX”

as an objectified category that will behave in such and such a way. Instead of

expecting someone, categorized as belonging to a certain group, to have those

traits, we expect every individual we meet to be a good person. And we imagine

that all these individuals coming together could perhaps do lots of joyful

things. For people who claim to believe in nothing, we are actually quite

optimistic.

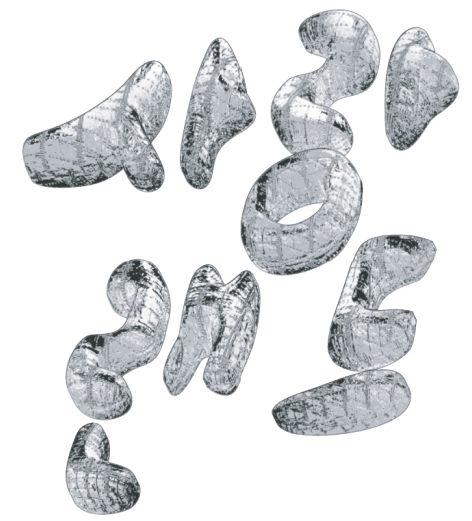

To

be together joyfully, the word we use is “barrier-conscious.” Just as dianalab

and the Infoshop Café Byeolggol have been appropriating the zine in completely

different ways, so too with this concept.