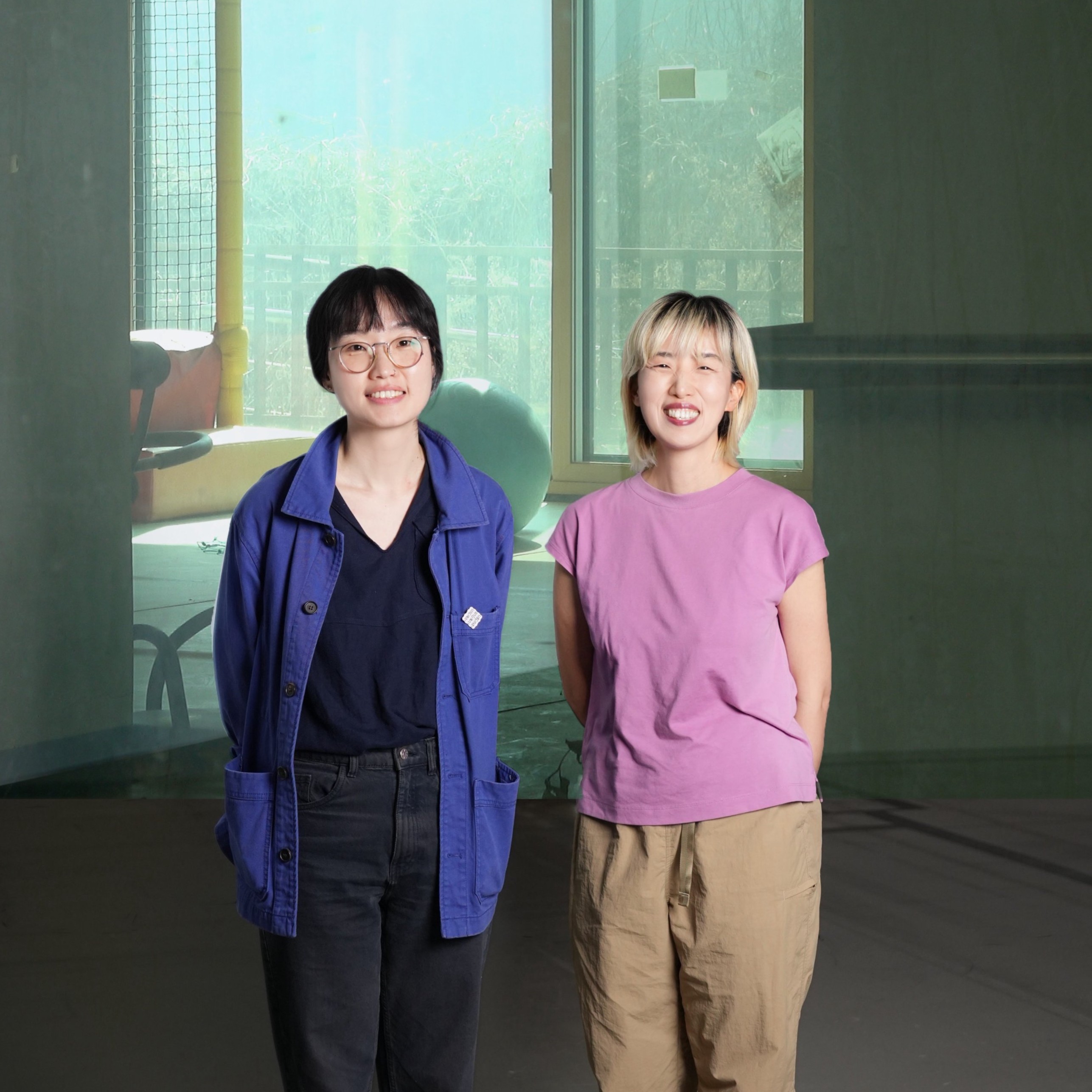

Since

this is our first column, perhaps it is best to begin with an introduction to

the group “dianalab.” There have been many discussions within the group about

how to present dianalab to the outside world, and although it may not be

immediately obvious, we have been continuously revising this introduction

little by little. As with anyone, introducing oneself to a stranger in just a

few short sentences is always difficult and always insufficient.

Whenever we

think about what words we should use to describe ourselves, we inevitably run

into walls. We often end up frustrated and making compromises in the face of

questions like, “Do we really have to use this word to describe ourselves?”

In

the beginning, we used the phrase “expressions with people with severe

disabilities.” Most of us at dianalab have lived for a long time as nondisabled

people who meet and work with those socially categorized as “disabled.” Some of

us have spent many years teaching art classes at welfare centers for the

disabled, or at night schools for disabled persons (though we hesitate to call

them “art classes,” that is often how they are perceived). We were also once

active in an artist group, now defunct, that included many artists with

developmental disabilities. At the time, they introduced themselves in this

way: “Those who have not received formal art education.” They did not use the

word “disabled” at all, but when we saw them speak about something that only those

without formal art education could do, we felt a kind of small exhilaration.

The

phrase “those who have not received formal art education” does not mean that

the group was made up 100% of such people and that no one else could join.

Somehow, it felt like it wasn’t so rigid. Instead, it gave the impression that

“those who have not, or could not, or even if they did, did not fit with it”—in

other words, whether they wanted to but couldn’t, or did not want to—anyone who

was somewhat outside society’s standard criteria could belong. Of course, such

impressions and reality inevitably diverge, but still.

Presenting

a point of departure that differs from the world of formal art education is

crucial not only when talking about disability culture and art, but also when

speaking about other forms of minority art. The issue is one of orientation:

where is the goal, what is it we are to become? Is the model of life one in

which you study hard, get into a good university, meet good mentors and

teachers, become a successful artist, and, if life goes well, make a lot of

money and become famous? Can we present such a path to people with disabilities

in a society that has been created and maintained for thousands of years

centered on nondisabled people? Who presents it, and who has the right to? Even

if someone presents it, should they? These are the kinds of questions we face.

This

may be similar to the expressions “in a hetero-centered society” or “in a

male-centered patriarchal society.” As women ourselves, when we see women break

through the glass ceiling and succeed in a male-centered society, we feel joy

and want to applaud. At the same time, however, we feel ambivalent: we cannot

do that, and we do not want to. As poor young people, as women, and as queers

who have never once lived as regular employees, success often feels like a very

distant story. How hard would we have to work to become like that? Our lives

are already doomed in this lifetime—so what should we do? Surely we are not the

only ones to have such thoughts.

Returning

to the subject of introductions: when we live avoiding this word and that word,

in the end we become beings that no one can quite figure out. We actually like

that about ourselves. We have long heard people say, “I really don’t know what

they’re doing.” And because we are artists and planners, and also people

constantly thinking about when to reveal “woman” as part of our identity, we

find ourselves hesitant to utter certain words—especially in contexts where

they could place us in a position of power (rare though that is, but it does

occasionally happen), or in contexts where they would only harden stereotypes.

This is particularly so if, as nondisabled people, we are to speak about

“disability.”

The

mere utterance of the word “severe disability” immediately elicits reactions

like, “Ah, so you’re working with people with disabilities,” or, “What a good

thing you’re doing. How admirable.” These kinds of responses come back all too

easily.

What

we most want to avoid is the interpretation of “nondisabled teachers helping

people with disabilities.” We ourselves identify as social minorities, and our

identities and desires—our thoughts on minorities and the practices arising

from them—have drawn us strongly to work with those socially categorized as

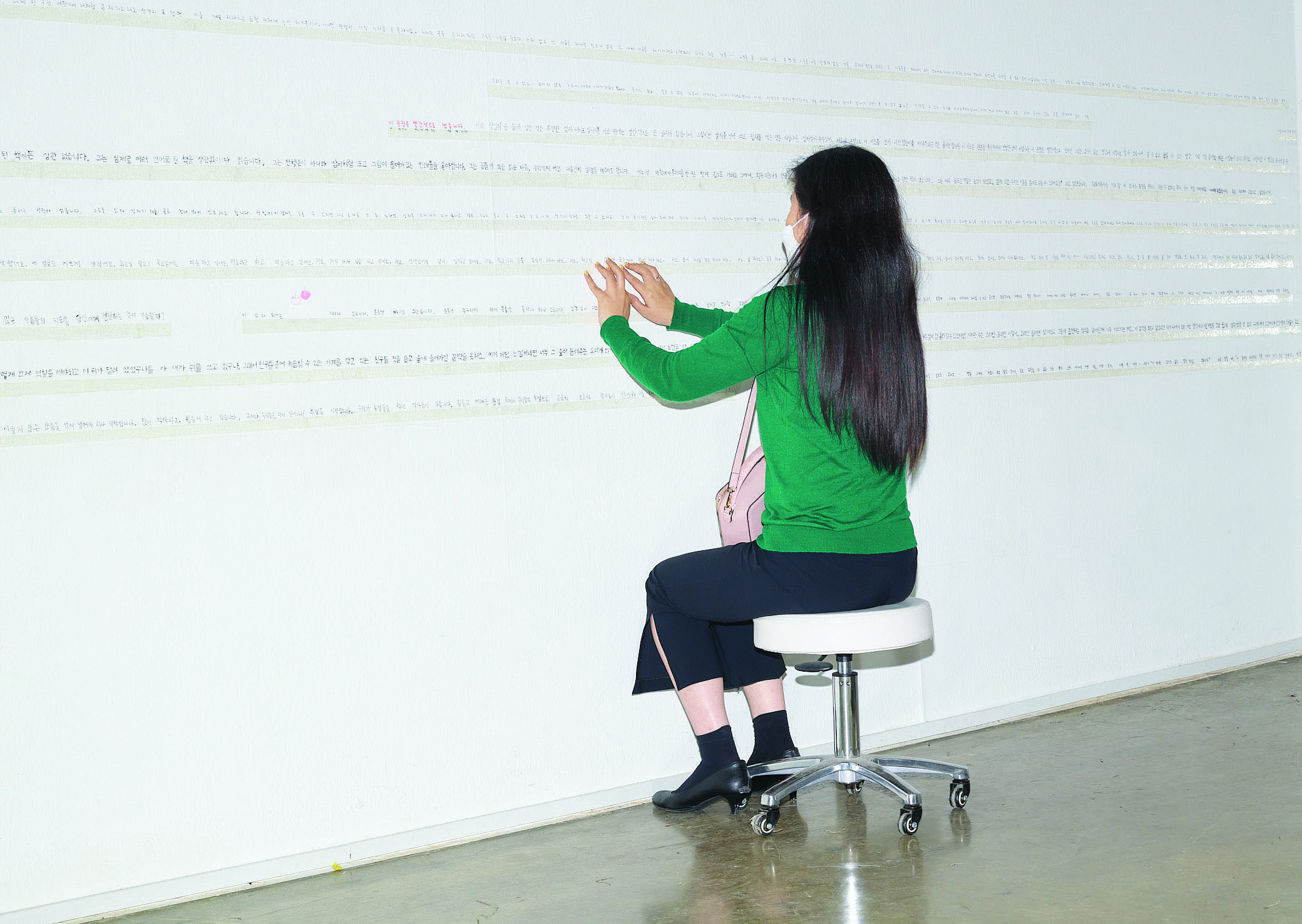

“disabled.” That is how we have arrived here. While working as dianalab, we

naturally stopped eating meat. Meat, disability, women, queerness, art… what do

they have to do with one another? They are in fact very closely connected. At

least for us, they are. And that is why we cannot help but do the work of

“meticulously shaping everything—from the physical space, to the moment, to

even the invisible air.”

For

the people called dianalab, for their friends, and for all those who may not

know us but think in similar ways, we have no choice but to think of the

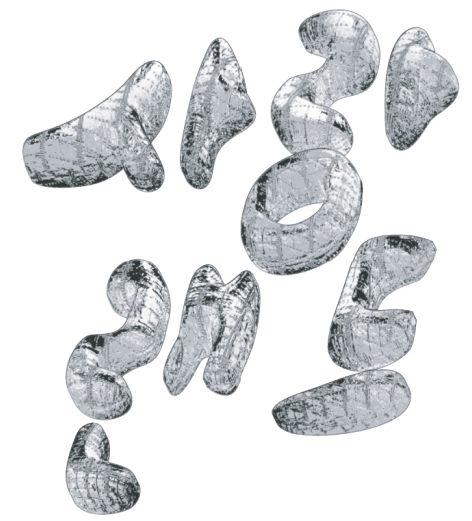

“whole.” That is why our work may appear to stand aside from the keyword

“disability,” and why one might wonder, “What on earth are they saying?” In the

next column, we will explain what kinds of work we have done with this

orientation.