Each

individual word used within the title of Sang A Han’s solo exhibition holds

multiple meanings. The word ‘sharp’ normally refers to the thin, pointed end of

an object and can therefore give a sense of intimidation. However, at the same

time, it also signals such thoughts or tricks, which then infer the possibility

of breaking through a problem that presents itself. ‘Courage’ refers to a

steadfast energy or a righteous attitude held towards the world, but the word

in Korean can also denote a container that holds objects. The artist may well

have been trying to point out the ambivalent nature of human beings by choosing

such words with dual meanings. The scope of perception given to people in

differing magnitudes, and the varied shapes of people’s hearts within that

boundary, are expressed through unfamiliar, as well as familiar states in the

real world. Han’s previous works focused on depicting, in a more definitive

language, the events she had experienced or the environments she encountered in

her social roles as a woman, mother and wife. In contrast, the phrases she

presents in this exhibition are implicit and metaphorical, with 《Sharp Courage》 also being a title that

speaks to that narrative.

Rather

than developing a piece around a specific time or event, as she had done in the

past, the artist now looks to contemplate all aspects of everyday life that

continuously unfold and visualize a fragment of the emotions felt within them.

During a conversation with the present writer, Han explained that she wanted

her voice to be hers alone, but at the same time not linger as a solitary

monologue. There will be certain emotions that everyone shares as fellow human

beings. Anxiety about the future, a sense of security arising from the

collective body that we call family, a desire to be recognized by society, an

internal conflict surfacing amidst contradictory values. All these emotions are

internal waves that each appear before us at different points in time in

diverse shapes and colors, and are realized as images of various weights and

sizes within this exhibition. Han wants to actively and widely share the

genuine worries and insights she feels as a person wanting to live the present

day in equilibrium despite being a fluctuating principal.

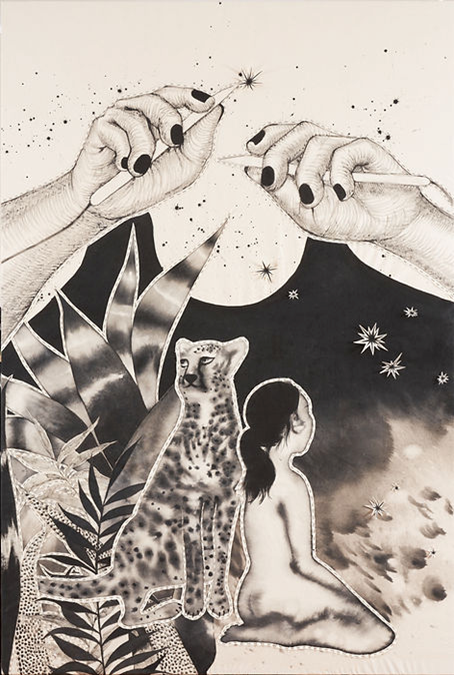

With

the shift in conversation topic, the realistic expressions that once stood out

in Han’s work have now been replaced with much more unfamiliar shapes.

Configurations of rows of sharp-pointed bumps, circles with black-filled

centers, crooked waterdrops, round or pointed pillars, vast expanses of empty

space. Han’s drawing style, which had previously been tightly bound in a

subject-and-predicate structure, transforms into ambiguous and slack symbols.

In addition, the figures appearing amidst the geometric shapes are drawn in a

state where their entirety cannot be clearly determined. Rather than specific

characters, they are closer to a visual substitute for the notion of a human

being. If you look a little closer, what you see filing the frame isn’t a simple

shape, but rather an abstraction of reality and actualities that closely meet

one another, such as the sky and sea, the sun and moon, the stars and clouds,

fire and water. Bizarre scenes that began from natural motifs remind us of the

universal logic of life. The sense of awe you feel before nature makes you

think of the weight of life and death, and the starry night sky reminds you of

the network of relationships between people that’s as expansive as the

universe. In addition, the geometric shapes, symbols, symmetrical composition

or ascending structure that appear in the pieces act as a mechanism to draw in

transcendental narratives into the work. In general, the scenery captured in

religious paintings refers to an unknown force beyond our actual dimension,

triggering psychological states such as awe, fear, healing, faith, belief and

hope. However, rather than mentioning the object of transcendental worship by

drawing in the code of mythology or religion, the artist means to focus on the

actions of extremely secular beings. In short, for the artist, the journey to

form relationships with people, establish a small society and find her place

within it is considered to be the most noble and honorable, above any other

task.

Meanwhile,

the materials used by Han have the physical properties that she feels most

comfortable with and, equally, were chosen according to need. For Han, the life

of an artist is not achieved metaphysically in another place separated from

here in this moment. Rather, it continues within a place that’s in extreme

close contact with everyday life, in an incredibly difficult and intense

manner. Traditional Korean ink ‘meok’ and fabric were most definitely a medium

that supported Han to continue her artistic experiments, not in well-equipped

studios, but even in the most restrictive of environments. Furthermore, these

materials possess multi-layered properties, and are very similar to the

messages her most recent works strive toward. By nature, ‘meok’ penetrates deep

into any gaps and stays there for a long time rather than floating across over

the top of a given surface. In addition, the pigments that may only seem black

actually have the potential to express countless shades of light and dark

depending on their background and concentration. The fabric may be weak in

front of the sharp protrusions, but it is a tough material tightly woven with

the warp and weft. Han continues her work based on these warm but robust

physical properties. The shapes of an impenetrable heart from within her mind

become images with outlines, and these soon become thin pieces overlapping each

other upon another frame. The artist then repeats the labor-intensive process

of packing cotton between the black and white fragments and sewing them with

thread, steadily weaving a world between reality and non-reality.

The

active practice of sculptural techniques such as dangling, stacking and

hanging, using the objects made from ‘meok’ and fabric, is particularly notable

within this exhibition. The high ceiling and lengthy walls that stretch out

extensively become the backdrop upon where compositions of varying sizes and

weights find their place. The exhibition space, which embraces installation

methods that reflect the principles of mobiles, hanging scrolls and towers,

opens out in front of the audience almost like a stage for a play. Han may well

have recognized in the first instance that what she was creating would not

remain as an afterimage on a flat plane, but rather, that these objects had the

volume to occupy a three-dimensional space, or even a dimension beyond that.

The dark and pale scenes extending out along the horizontal and vertical axes

of the exhibition space become the bounds that embrace the vast skies, the

moon’s halo amidst darkness, the stars scattered across the heavens and the

lives of myriad small existences.

The

profound senses engraved upon the artist’s body as she passed through various

hurdles in life become authentic existences wearing a harder outer shell and

blend into the landscape. In fact, what Sang A Han set out to say from the very

beginning sits close in line with a perpetual theme that has inspired and

intrigued numerous artists for a long time. That is, the fundamental forms

found underlying the psychological reactions that circulate within a human

being’s lifetime. We recall how emotions such as anxiety, joy, sadness,

compassion and love have taken on different forms and moved through styles of

art depending on the times. Additionally, the more surrealistic allegory that

Sang A Han has adopted further extends the breadth of meaning her work is able

to achieve. Han’s voice has now amassed the speed and scope to also embrace the

experiences of strangers with the words spread out through her canvas. Her

voice no longer lingers just with herself. Han is stepping out from her own

domain and cautiously striking a conversation with this world of yours and

mine; it is now time to welcome her courage and open up our own stories.