Kwak

Intan’s formal approach has consistently unfolded by dismantling the boundaries

between media. In his early works, he used traditional materials such as

plaster and resin to embody psychological states, but soon expanded to steel,

cement, stainless steel, and acrylic, layering material strata. In 《Unique Form》, he dismantled and

reconstructed earlier busts and juxtaposed them with historically referenced

works, resulting in a formal hybridity where sculpture and painting, fragments

and completions, past and present were intermingled.

In works

such as Sculpture Gate: Development of the Head(2020),

the boundaries between pedestal and sculpture themselves are blurred. Sculpture

is no longer a fixed object placed on a base, but a fluid presence in which

fragments and structures exchange positions. This strategy dismantles the

hierarchical order of sculpture and repositions even peripheral elements as

integral to the work.

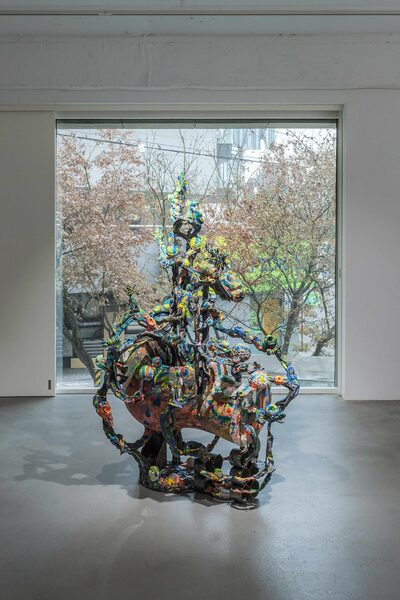

In the

‘Movement’ series, the illusion of motion becomes

central. Movement 21-1(2021), composed of resin,

acrylic, and steel, transforms the otherwise static medium into a dynamic event

through its tactile surfaces of vigorous flow. Rather than smoothing material

surfaces, Kwak reconfigures fragmentation and reassembly to sculpturally embody

traces of movement.

Since

2022, painterly elements and digital techniques have been added. The ‘Palette’

series layers clay, resin, and acrylic to create painterly surfaces; in

particular, Palette 2(2022) merges references to Kim

Whanki’s blue stars, Rodin’s busts, and emoticons.

In Intersection of Sculptures 1(2023), hand-formed

fragments intermingle with 3D-printed elements, positioned atop the lines of a

traffic intersection. Here, the real and virtual intersect to form an organic

space. His formal language no longer remains within traditional sculpture, but

expands into an experimental arena where painting, digital media, and playful

signs collide.