Have

you ever reflected on the 50-won coin, now nearly obsolete under the pressure

of murderous inflation and the dematerialization of value as a store of wealth?

I imagine that few young people today would pause in thought upon seeing the

rice stalk engraved on the coin. The rice variety depicted on the obverse

is Tongilmi. With the onset of the postwar baby boom, rice production

began to lag, and the government poured its efforts into breeding new

varieties. Crops vulnerable to environmental conditions everywhere underwent

histories of artificial hybridization, and the East Asian preference for

Japonica rice finally met its solution through a man named Huh Moon-hwe.

Serving as a professor at the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Seoul

National University, in 1964 he requested a dispatch to the International Rice

Research Institute (IRRI) from the Rural Development Administration, then

grappling with the rice crisis. Working at this institute in the southern

region near Manila, Philippines, his repeated hybridizations ultimately bore

fruit in the creation of Tongilmi. Though it later fell into disuse due to

its poor taste and susceptibility to cold damage, Tongilmi was

nonetheless widely cultivated across South Korea, meeting the nation’s rice

demand and, as an image, earning an eternal guarantee by being inscribed on

coinage.

It

is self-evident that hundreds of crossings must have been undertaken to secure

a single variety of Tongilmi. Such artificial selection is minuscule in

duration compared to the scale and history of natural selection, and in certain

domains it is difficult even to draw a strict line between the two. The desire

to avoid becoming the unfit within nature is always osmotic and reciprocal. In

the long historical process whereby the wolf became the dog, was only human

desire reflected? Both dogs and humans projected their desires onto one another

and evolved accordingly. Dogs, becoming gentler, more loyal, more lovable,

fulfilled the species mandate of flourishing within the fences of human care.

This cannot be explained merely by the short two centuries of modern breeding

culture. Thus, the very concept embedded in the word “artificial selection”

distorts reality by separating humans from nature and concealing the

reciprocity of desire. All beings in nature experiment with programs that

imagine and design the position of the other—whether species, instinctual, or

conscious—as partners in the realization of desire, just as flowers and bees

do. The flower seeks reproduction; the bee, nectar. In this scheme, who,

indeed, is the subject of desire, and who the object?

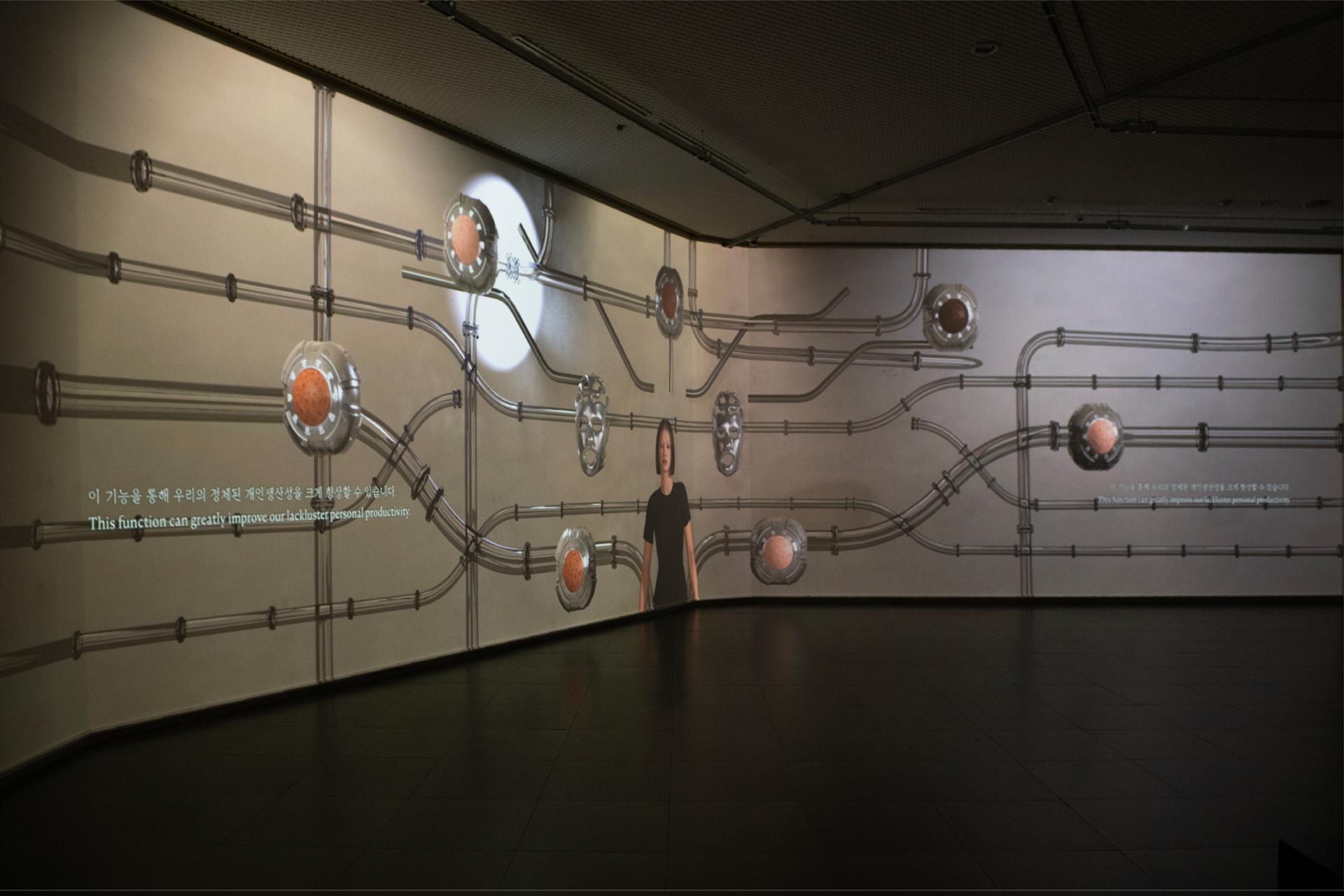

We

can read a similar map of desire in the work of Sora Park. In 《Meta Beauty Innovation》, staged in the form

of a product launch, as if to declare that the aesthetics of novelty today

exist only in commodities, a wearable device called ‘‘Eye Meta’’,

reminiscent of a facehugger, is advertised. It is a cosmetic device that can

reflect rapidly shifting trends, update itself in real time, and adjust beyond

the control of its user. In the video, the repeated pitches of the “Doctor”

sound less like the trappings of science fiction, digitality, or futurity than

like urgent issues of today. ‘‘Eye Meta’’ can “predict how many

‘likes’ one might receive on social media,” thereby maximizing the “labor

productivity” of influencers who monetize attention.

Despite the Doctor’s

insistence that the device “transcends evolution,” it still appears to remain

within the frame of environment and adaptation, as a problem of desire

circulating inside that framework. A strange game begins within the household

of the attention economy. Each party, like flowers and bees, gains something

and gives something up. Audiences gain visual gratification and consume

advertisements; influencers gain attention and revenue while exporting

pleasure; advertisers pay money and gain traffic; and the platform siphons

profit from all three. A sacred gambling table is set, one on which it seems

that no one will lose.

The

power formula of ’Eye Meta’, which drives such an economy, is noteworthy.

An organism’s appearance depends on a kind of spontaneity that arises within

the desires of others. For a certain appearance to be considered beautiful, it

must be rewarded through the act of being seen and the radiance it emits.

Beauty is not an intrinsic essence derived from the harmony of the eyes, nose,

and mouth; rather, it resides in the act of being seen. The more intensely the

radiance refracts through the gaze, the more strongly it is transmuted into

allure.

Because radiance must be concentrated through the magnifying glass of

another’s eyes, those eyes become a camera obscura through which

beauty is projected. Thus, appearance is less an indivisible relic owned by the

self than an asset fluctuating according to complex temporal scales. ’Eye

Meta’ inclines away from fixed, stable appearances and toward a portfolio

method that detaches them from temporal determinacy. Now, appearance is active.

No longer determined unilaterally by external evaluation, it behaves instead as

a skilled investor, predicting and responding to how judgments will be made.

In

this process, ’Eye Meta’ acquires a kind of sublimity. Until now, the

radiance of appearance had always presupposed an ontological reciprocity: one

first bestows radiance upon others, but it is only with the guarantee of return

that such radiance exists. Yet the ultimate altruism of ’Eye Meta’ transforms

the radiance of appearance from something biological and organic into

effortless “likes,” converting the emission of light into an index, and drawing

spectators into its circuit so that they, too, become part of the radiance’s

pilgrimage. Self-sufficiency and exaltation in the act of being seen are gone.

What remains is a flash aimed indiscriminately at others—an artificial sun.

This inorganic, metallic magnetism imprisons the wearer beneath the skin, repositioning

them into the realm of precious metals. If jewelry’s radiance traditionally

enhanced its wearer, ’Eye Meta’’s glow petrifies the user into

mineral form, Medusa-like, rendering them radiance-itself. Upon this fallen

sublimity, trends reflect moment by moment, never crystallizing into a stable

image—appearing instead as if a face trapped within were desperately struggling

to burst forth. Every trend vying to crown itself as the trend

competes endlessly in real time.

Now,

attempts to find consistency in the face or to endow it with the essence of

subjectivity are bound to fail. The image of Tongilmi rice conveys

stability because its replication guaranteed a consistent indicator of value

(50 won is always 50 won). Yet this stability was always a fiction. The

stability of currency could only be registered once the economic reality—that

its value is constantly eroded by inflation—had been concealed. Likewise, the

sameness promised by human appearance was always fictional, undermined by the

factors of aging and the evaluations of others, but guaranteed only by ignoring

this reality. ’Eye Meta’ is, in contrast, brutally honest. It lays

bare that the system of the face belongs within the evaluation mechanisms of

assets, and demands continuous adaptation. The appearance I believed to possess

was valid only in the functional sense of eyes, nose, and mouth; as a

decorative image arising from their assemblage, however, appearance belongs to

the opposite realm. ’Eye Meta’ directly strikes this truth: that what

we took as immutable essence is in fact exposed as fiction.

In

the past, what allowed one to sever from particular styles or trends was

uniqueness itself. Uniqueness was the source of aura, the very ground on which

art secured its place in opposition to craft. But the ontological comfort once

guaranteed by the uniqueness of the face—like a fingerprint—corrodes under the

cultural dominance of ’Eye Meta’. The mark of uniqueness, created through

the idiosyncratic arrangement of eyes, nose, and mouth, becomes a relic of the

past. Eyes, nose, and mouth, simply by “being attached,” reveal themselves as

decoration. And decoration, by definition, can always be replaced.

The

obsolescence of the face as an old model is amplified by the rarity of ’Eye

Meta’, which only 500 individuals can own. Now, synthesis is no longer the

interaction of eyes, nose, and mouth. Once, the complementarity of those

features formed expressions from which one could infer the soul, but the era

has changed. The capitalist alienation that separated ownership from being now

constructs a phantasmagoric heterotopia, wherein possession of ’Eye Meta’ constitutes

existence. The metallic fluidity of radiance-itself is augmented by rarity,

visually marking social power and status. The halo migrates, historically

transformed, from the background to the forefront, radiating outward from the

face.

‘Eye

Meta’ can be seen not only visually, decoratively, and functionally, but

also symptomatically. “Our future depends on how quickly we can change,”

declares the Doctor, making ’Eye Meta’ appear less like a luxury for

influencers than like a survival kit. In this sense, ’Eye

Meta’ becomes not simply a superfluous accessory but a necessity,

something one must acquire. Adaptation to change is both the effort not to be

excluded in an accelerating world and the very battlefield on which all beings

have struggled since the dawn of life.

Because ’Eye Meta’ “automates”

the analysis and reflection of data, adaptation no longer belongs to subjective

capacity but to the problem of performance and imitation. And imitation has

always been inseparable from fashion. The speed at which one imitates fashion

has long served as a marker of class. Since fashion reveals hierarchy, we must

look past the illusion that it “passes by” and recognize instead that

it flows downward. To participate in this flow is to both situate oneself

within a particular style and stratum and distinguish oneself from lower

strata. Thus, ’Eye Meta’ compels us to choose between extinction and

imitation: to sink into ruin, or to enjoy comfort in a bunker.

We

may now analogize ’Eye Meta’’s figure with that of Tongilmi, which

stands at its very opposite pole. Tongilmi achieved a kind of

eternity, but it could not withstand the accelerating changes of inflation and

the dematerialization of the world, and so it was phased out. Its decline in

value rendered it invisible, compounded further by the diversification of

payment methods. ’Eye Meta’, on the other hand, cannot achieve any stable

form, and thus seems to guarantee nothing—yet paradoxically captivates us with

the sense that it will never be flung outside the flow. This

liquidity—recalling Zygmunt Bauman’s “liquid modernity”—is capital’s liquidity,

and touches the liquidity of our lives as well. The surface of ’Eye Meta’,

which shelters us and conceals us within its flow while rescuing us from the

threat of being washed away, may be likened to a newly sprouted horn for

humanity. But of course, having sprouted new horns, we can no longer be

classified as human.