Jamyoung

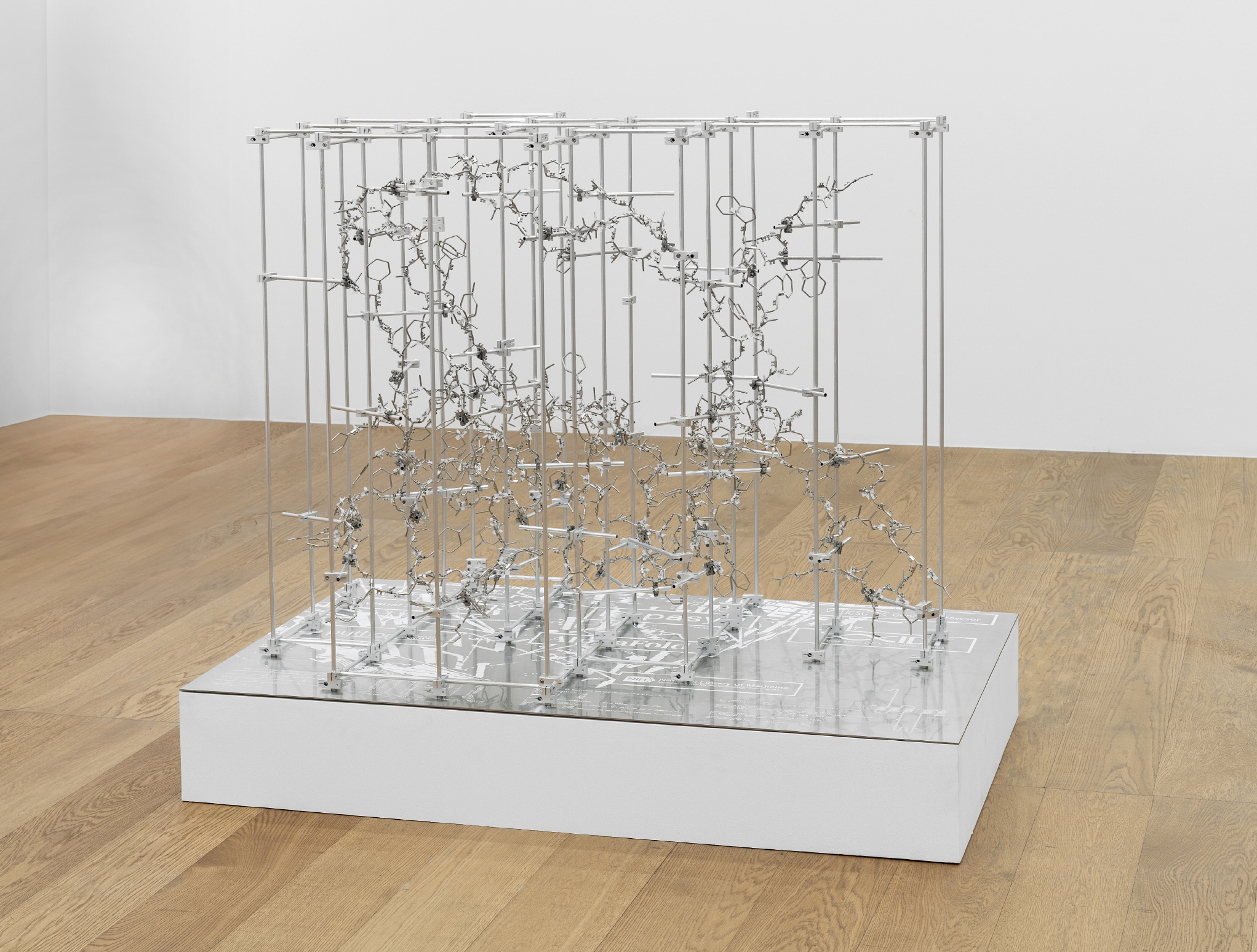

Koo’s work, which generates bodies of software through the logic of genetics,

verges on science fiction. Attempting to grant software the status of a

quasi-organism, he approaches genes as a kind of software. To juxtapose the two

requires extending the idea that software is a program of life endowed with a

body, and conversely, that the human being — grounded in genetics — can be

regarded as the sum of software. Pushing this logic further compels us to

reconsider the artist’s subjectivity. In a sense, he is a mediator between

software and genes, a hacker and translator who selects, disturbs, and

crossbreeds disparate programs. His pursuit of sculptural DNA through the

blueprints of genetics and software recalls the autonomous creative

subjectivity celebrated since the Renaissance. Yet what must not be forgotten

is his original sense of helplessness toward software.

He

cannot escape software: he appropriates it as subject matter, employs it to

confer form, and relies on its coded metaphors of natural elements as the

source of meaning-making. Thus, he remains tethered to software programs. His

stance of appropriation, of treating software as both methodological object and

tool, recalls Nicolas Bourriaud’s notion of the artist in the “postproduction”

era — one whose labor is based on cultural reference and appropriation,

remixing the oversaturation and circulation of information into personal logic,

much like DJing. But considering the helplessness rooted in contemporary

artists’ dependency on diverse tools and materials, one might instead emphasize

the struggle to regain agency from an inverted position where subject and

object have been reversed. Could his sense of helplessness toward completed

programs not itself have functioned as the motif for dismantling, designing,

and visualizing their bodies?

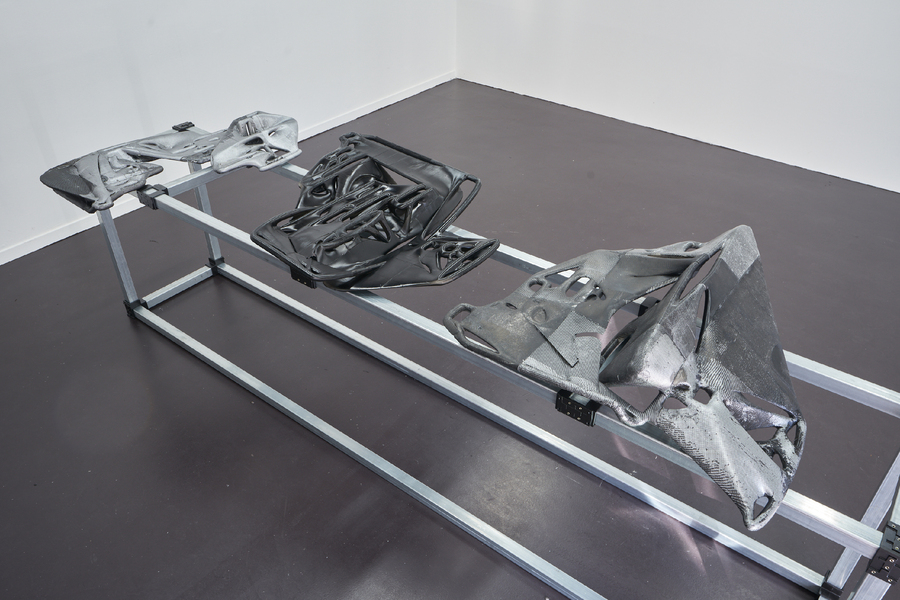

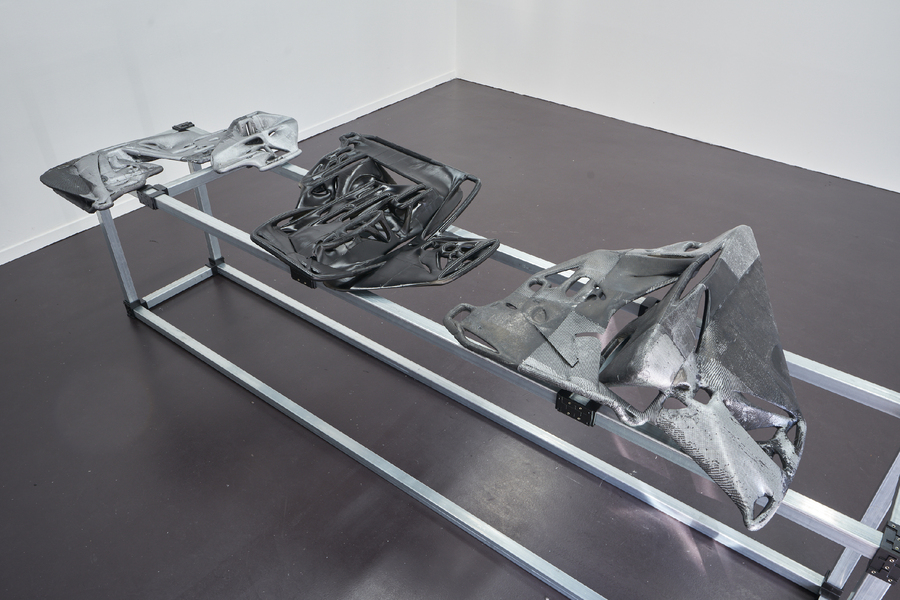

Thus,

to see his equating of program blueprints with DNA sequences and adopting them

as sculptural grammar merely as a tool for formal experimentation would be too

narrow a reading. While the objects may appear as outcomes cross-produced from

software, they are in fact hybrid fleshes rooted in program-dependent

subjectivity. The artist acknowledges his alienated, dependent, marginal, and

secondary status, while nonetheless exercising agency by selecting and layering

disparate programs. The casted fleshes, too, are results produced through the

very programs that alienate him. Even if he remains bound to and dependent upon

software, he continues to attempt a reverse transcription of objecthood —

striving ceaselessly to enact subjectivity as an object.

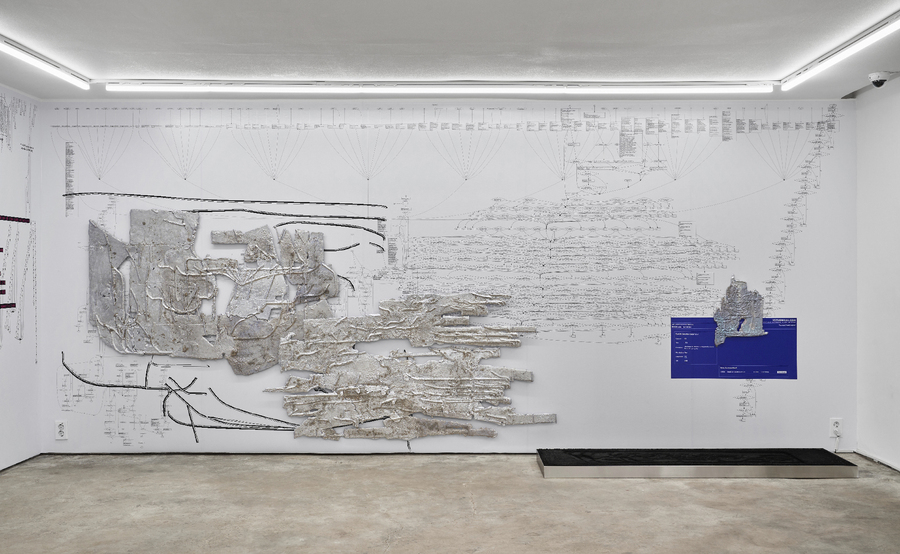

Obscene Evolution of Form

His

methodology evolves from aligning program code with molecular genetics to

expanding across e-commerce industries and archaic atomism, staging an obscene

evolution of form. Recently, his experiments have extended to hacking North

Korean websites, sequencing their page structures into genetic-like orders, and

sculpting them. These websites, though officially inaccessible in South Korea,

can be reached via VPN — but visiting them, even through circumvention, risks

drawing the scrutiny of state intelligence. Here, the relationship between two

antagonistic blocs emerges: antagonism as a means of mutual exploitation and

maintenance. His work overlays such relations of reciprocal expropriation and

collaboration. The question then becomes: what skeletal frames and fleshes will

the artist attach to this entrenched antagonistic dependence? His sculptural

experiments, operating at the scale of micro-engineering, inevitably bear

political undertones.

However,

one must note that by reducing programs to code values as units, his method

excludes program functions, contexts, and uses. Thus, to directly link the

visual attributes of his objects with the functions or applications of the

original programs would be an arbitrary interpretation. His forms, produced

solely from code values stripped of context, take on the status of grotesque

entities with no direct correspondence between content and appearance. These

alien forms, born of programs’ obscene cross-breeding, possess a kind of

reproductive sculpturality without bearing relevance to the programs’ functions

or meanings. At the very least, one can say that arbitrary applications — such

as natural material arrangements recalling archaic atomism — cannot yield full

coherence. If his method inevitably embraces the arbitrariness and chance of

assemblage, then what new material demands or deviant leaps will his next

objects attempt?

Another

perspective is also possible: his method of deconstructively appropriating

heterogeneous software could itself be regarded as a meta-software. If so, how

might his methodology, as software, achieve critical form through

self-appropriation? Would not such a supposition risk reducing his obscene

updates through translation into mere asexual reproduction, rather than hybrid

renewal? Where, then, can mutation and chance — the dislocations that disrupt

the grammar of form — intervene? Could this not become a variable in the unruly

relationality between program and artist, exceeding their dyadic relation even

as it remains within it?

Footnote (1)

His

experiments with aberrant arrangements, juxtapositions, and translations,

recalling viral reverse transcription in molecular biology, are not forced

analogies. For example, RNA transcribes DNA’s information outward to synthesize

proteins, sustaining life. In the case of the HIV virus, however, RNA enters

cells and reverse-transcribes into DNA, multiplying within the host. As Susan

Sontag has noted, metaphors of infection — rife with images of destruction and

damage — have proliferated into militaristic language about viruses invading

and devastating the human body. Yet shifting the perspective, one may see the

body as always open, not merely an object or victim of viruses. Rather, it

welcomes them, undergoing transformation and evolution through mutual affect.

As anthropologist Bokyeong Suh suggests, the body is not simply invaded and

destroyed but experiences resonance, transformation, and repeated evolution

alongside viruses. In this light, Koo’s work resonates with RNA’s reverse

transcription — transcribing DNA to sustain life and reproduction. For

more on DNA, RNA, viruses, and the body, see Bokyeong Suh, Entangled Days

– Building Futures with HIV, Infection, and Illness (Banbi, 2024).