In

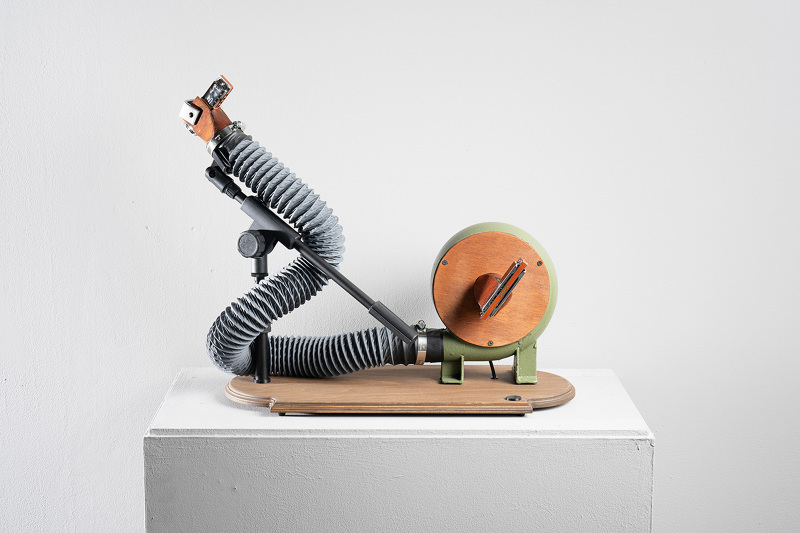

2021, Sunghyeop Seo presented the exhibition 《Performance for Topological Sense》. The

exhibition consisted of machines built to generate sound autonomously:

paravan-like forms made of wood, architectural columns reminiscent of Western

antiquity, combined with components such as the Korean traditional percussion

instrument sogo or the strings of Western string instruments. A performance

followed, in which Korean traditional musicians joined to produce sound

together.

Understanding the World through Topological Sense

Let

us first consider the word “topology” from the exhibition’s title. More

precisely called “topology” in the mathematical sense, the term derives from

the Greek topos (place) and logos (study). Defined as “the branch of

mathematics that studies the laws of forms or spatial relations of points,

lines, and planes,” it is rooted in geometry. Yet while geometry concerns

itself with measurable aspects such as length, area, and angle, topology

instead addresses “geographic” relationships— adjacency, connection,

containment—between points, lines, and planes. Topology, then, is the attempt

to define an object by its relations with its surroundings. Seo appended to

this the term “sense.” Sense relates to how humans perceive external stimuli

through the body. We listen with our ears, smell with our nose, touch with our

fingertips—we sense external objects, and this sensory information constitutes

our cognition. Thus, topological sense can be understood as Seo’s attempt to

speak about how we perceive the world and construct cognition relationally.

Crossing the Categories of Understanding

This

problem of sensation and cognition was concretized in the performance that

combined sound-producing machines programmed by Seo with traditional Korean

musicians. The Sound Paravan pieces, which grafted

violin, viola, cello, and contrabass strings onto paravans, looked somewhat

like upright geomungo; the combination of sogo and paravan resembled a

mysterious instrument from an unfamiliar country. These machines also performed

together with players of Korean traditional instruments such as gayageum,

geomungo, and sogo. In their appearance, these machines combined the Eastern

form of the paravan with Western string instruments, while the performers being

Korean musicians also meant the work traversed the grand dichotomy of East and

West that has shaped our modernity. The dichotomies of East and West, reason

and emotion, human and non-human (as Bruno Latour has argued) were long taken

for granted, but in fact served to establish hierarchies and justify violence

against the other.

In

terms of performance, the musicians only learned on the day of the show that

they would be improvising with these programmed, sound-producing machines. The

human musicians, listening and responding to the machines’ output, created a

new event of relationship between human and non-human through sound. The

exhibition also traversed genres: it was an “exhibition” containing a

“performance” by musicians, and the improvisatory nature of playing with

machines never before encountered underscored this. The machines’ visual

subversion of boundaries was complemented by sound performance, which resonated

through the exhibition hall as auditory stimuli resisting definition by our

existing categories. In this sense, Seo can be seen as traversing not only

genre, but also the categories of world, perception, and art itself. What is

crucial is that the events occurred not at the level of cognition but at the

level of sensation. Early in his experiments, Seo allowed performers to

manipulate the machines themselves.

Yet more important than the production of

intentional, composed music was the topological field of sound created by the

overlapping of individual sounds. He did not seek musical results. Music is a

convention, thus human, thus cognitive. Its long history of forms, scales,

rhythm, and harmony all reflect human rules. But in Seo’s works, the sounds of

the machines, the responsive sounds of the musicians, and especially the

vocalizations of Minwang Hwang (guh-eum, vocal soundings of Korean tradition)

together produced sounds that were equally non-human and sensory rather than

cognitive. As co-equal sound-producing agents, the machines and humans refused

hierarchy. The sounds that emerged between notes and tones created new

topologies and networks of relation at the level of sensation.

A New World Brought by Coming Relations

Seo

majored in design. This training seems to have enabled him to treat objects

with different methodologies, producing almost magical effects of perception.

Design and art, despite often being grouped under the umbrella of “art,” are in

fact opposing fields. Above all, their purposes differ: artworks exist for

appreciation, while design objects exist to be used. Differing purposes mean

differing fundamental goals for creators. Art speaks to the world, while design

responds to clients. Yet both converge in that they are creative practices and

both must listen to the medium—the material—through which they are produced.

Seo excels at listening to the stories of objects as media, and at translating

these into effects. His works and the effects they produce not only deepen

understanding of objects themselves but also allegorize the world through the

relationships objects create.

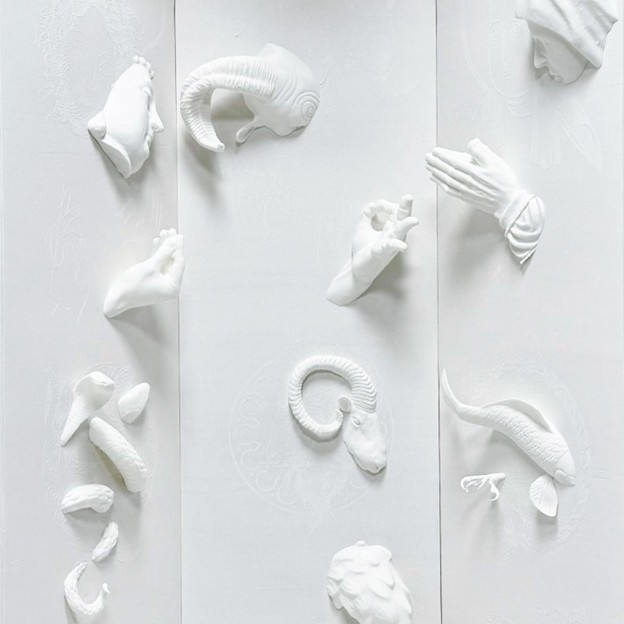

If

his earlier works were experiments with media that traversed perception, his

more recent works add narrative. In his upcoming solo exhibition, the new

objects will carry stories, detached from their original functions. Monument (2022),

for instance, consists of a tetrapod from a breakwater, topped with a Doric

capital and inscribed in Polish (Seo is married to a Polish artist with whom he

often collaborates). A single tetrapod has no function; only in groups does it

block waves. In this, it demonstrates relational rather than hierarchical

structures.

The stories written and spoken in Polish are, for Korean audiences,

inaccessible as language, persuading the audience instead through metaphor and

sensory effect, just as in his previous works. The fact that Seo’s hometown is

Jeju, an island defined by its border between land and sea, resonates with his

treatment of tetrapods as new sites of relationality. The contemporary efforts

toward reconciliation between human and non-human, toward treating all beings

on equal terms, seem closely aligned with island life, where human and

non-human were always more closely bound.

If

geometry exists to define the size of objects, topology finds its virtue in

articulating difference through relations beyond physical form. The topology

that Seo seeks to sense—and urges us to sense—strives to recognize difference

in a world where boundaries become restrictions and distinctions become

violence. Beyond exclusivist purity, acknowledging that we are all hybrids and

exploring the potentialities that lie within this condition: the multi-species

world that makes new relations possible is precisely the one Seo proposes when

he praises hybridity.