1.

Boma

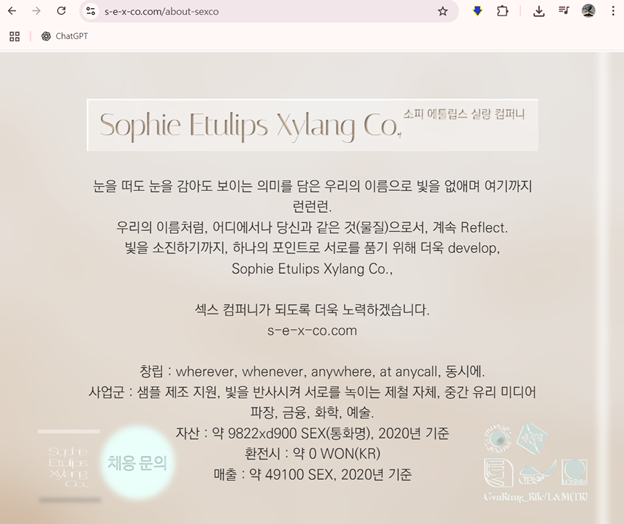

Pak’s solo exhibition 《Sophie Etulips

Xylang Co.,》 confers a concrete worldview and narrative

upon the various “fakes” she has experimented with over the past few years,

thereby more assertively revealing the underlying structure of her practice.

The title of the exhibition is also the name of a fictional company created by

the artist. Broadly speaking, what this company does is reproduce a particular

kind of hierarchy—a system that distinguishes between the real and the fake,

the sublime and the trivial, the valuable and the incidental. Considering that

the exhibition borrows the visual format of official websites of “real”

corporations only to erase the content one might expect from them, some viewers

may be inclined to interpret it through the lens of “mirroring,” a feminist

strategy.

Originally,

this exhibition was to be installed by “emptying out” an entire “respectable”

building with actual marble flooring. However, for various reasons, it was

produced instead using the unique affordances of the website medium. Like many

of Pak’s previous web-based works, 《Sophie Etulips Xylang Co.,》 also presents a

highly unfriendly (or “experimental,” in other words) impression due to its

absurdly long vertical scrolling, the background sound that gradually dissolves

into white noise, and the maze-like hyperlinks without any hierarchical

structure.

Moreover,

each menu and description that constitutes the website refuses to be captured

by any coherent “meaning”—whether that be as a capitalist commodity or in

patriarchal language. This reveals something that deviates from or exceeds the

simplistic one-to-one logic of “mirroring,” that is, the cyclical chain of

“returning what one has received.” It would therefore not be a stretch to say

that Boma Pak’s language—described as “like running it through Google

Translate”¹—deliberately targets communicative failure and heightens entropy,

staging the process through which she “becomes an object herself.”²

But

is that enough? In other words, is this steadfast “opacity,” which renders her

work difficult to access, merely an artistic gesture aimed at resisting

interpretation? Perhaps it is. This essay, which is closer to a preliminary

study of Boma Pak’s artistic world, is nevertheless written with the intention

of establishing a critical framework for what her work persistently references

as “the feminine.” How does Boma Pak’s work relate to the feminine? Why, of all

things, through such “opaque” methods? To answer these questions, we must

return to the concept of “mirroring.” That is, we must reconsider the

historically specific feminist (artistic) strategy of “mirroring” as a

still-useful premise that actively operates throughout Pak’s body of work. In

this particular case, however, Boma Pak’s black mirror does not reflect. It

absorbs.

2.

Can

we call Boma Pak’s work “feminine”? As I use the word “feminine,” I feel both

an urge to clarify what the term actually means and, simultaneously, a desire

to abandon the attempt altogether. The adjective “feminine” naturally

corresponds to the initial impression I had of Boma Pak’s work—“light and

pretty”—and that very description reinforces the prejudices produced by the

sex/gender system in which it is deeply entangled. In other words, if it’s

permissible to describe Boma Pak’s work as “feminine” simply because it deals

primarily with “light and pretty” immaterial elements such as “atmosphere,”

“scent,” “light,” and “surface,” then what exactly do I (and those who agree

with me) believe “woman” to be? “Woman” is pretty.

“Woman” is the light

reflected in a glass window, the scent that leisurely fills a space, the

surface of polished marble. “Woman” is an empty illusion. “Woman” is everything

that exists outside the material we can see and measure—in short, dark matter. What

I want to address here is the mode of existence of “women” that is already

embedded in the adjective “feminine.” If “masculinity” evokes a completed

heroic narrative earned through a kind of credentialing, then “femininity”

lacks content. “Femininity” is merely the atmosphere that surrounds something

deemed to be an essential quality shared by all women.

Borrowing

from Anne Carson—whom Boma Pak references in other works—we might say that

atmosphere, unlike nouns and verbs that name the world and set those names in

motion, aligns more with adverbs, which play a “purely incidental” role.

Atmosphere can always be manufactured if necessary (incidental), it is

naturally backgrounded (dependent), and if a similar effect can be produced, it

doesn’t have to be that exact thing (substitutable). Because of these traits,

one atmosphere can be swapped for another, and they all hold the same value.

But this variable, value-less quality of atmosphere—of the “feminine”—is not

biologically intrinsic to the female sex. In fact, an obsession with anatomy

and morphology would only hinder our effort to deal with what concerns us here:

atmosphere. The question is: what renders the “feminine” continually

worthless—and how?

In The

Market of Women, Luce Irigaray argues that civilization is

fundamentally based on a male exchange system that trades women while

simultaneously excluding them from that exchange. Since women hold value only

as evidence or products of male labor, they are abstracted and othered. Even as

“crude” commodities, the use value of women is only estimable by comparison

between products.

“Thus,

woman has no value other than her exchangeability. (...) As commodities, women

reflect the value of the male/for-the-male. Through this operation, women

surrender their bodies—sites of reflection and the material-medium of

contemplation—to men.”³

Before

Irigaray, Gayle Rubin had already applied Claude Lévi-Strauss’s notion of “the

exchange of women” to the framework of female oppression in her essay The

Traffic in Women. She writes: “If women are the exchanged, the ones

giving and receiving them are none other than men. Therefore, women exist not

as partners in exchange, but as conduits of relation.”⁴

From

this perspective, woman is a “material-medium of reflection and contemplation”

for the man; she is the adverb that links the male subject (noun) with the act

of exchange (verb). In other words, the woman-as-commodity, meaningful only as

exchange value, becomes both the “mirror” that reflects the male

producer/consumer’s desire and the “atmosphere” that fills the space between

them. The concept of “the traffic in women” should not be seen as the only or a

reductive analytic framework for understanding the sex/gender system. Still,

let’s hypothesize that this mechanism is indeed one of the essential

foundations of the economy, culture, and language of the civilization we live

in. From that angle, we could arrive at the conclusion that the historical

authority of the values we’ve “believed in” and been loyal to was actually

accumulated through the exchange of women by men.

And thus, the expectation

that one could earn equivalent value if one serves long and faithfully enough

is merely an illusion. Boma Pak’s work—particularly the worldview subtly

exposed in 《Sophie Etulips Xylang Co.,》—may well be understood from this perspective. After the site

finishes loading, the very first page we encounter on the fictional company’s

website is Words of fldjf studio. Unlike the following

pages that reveal the company’s “substance,” this page metaphorically conveys

the internal perspective of “fldjf studio” (hereafter “the studio”), which has

worked for “those distant companies” over the past several years.

Simultaneously,

it allegorically confesses the illusion and (perhaps still persistent?) faith

held by the feminine subject in relation to the

masculine/authoritative/traditional value system embodied by the “company.” The

company has only ever sent the studio “cigarette butts, paper scraps, and a

handful of air,” and it already ceased to exist 8 minutes and 20 seconds before

the two were to meet. Nevertheless, the studio not only prepares for the

company “the missed lights, images, and shadowed faces created by the suns that

live there,” but continues to “wait” for the company, describing their

relationship as one of “romance and magical aura.” Why? “Therefore, the

commodity worships the father, constantly mimicking and resembling the one who

substitutes for the father.”⁵

Could it be that the studio, like Boma Pak herself often does,

has simply “forgotten” that it has never had a relationship with the

father–man–company and never will? If we were to remember every minute of every

day that we had been eternally deceived, betrayed, and abandoned—if we could

never forget—we would lose all language. “‘I never wanted it, but the world

replicated and rapidly replaced for me sky, emotion, material, time... I took

it all thoughtlessly and was deceived into believing these things were given to

me, but soon realized they were merely images I could not control. Yet I forget

again. My artistic practice began from this feeling of betrayal and shame.’”⁶ Here, Boma Pak calls it “the

feeling of betrayal and shame.” So let us return to the question of

“mirroring.” Is what 《Sophie Etulips

Xylang Co.,》 presents simply a voided company, covered

over with meaningless “atmosphere”? Is it an attempt to return her own sense of

betrayal and shame? (But to whom?)

Footnotes

1.

Jiwon Yoo, “fldjf—Evaluating Satisfaction with the Service,” Pre-opening

Glass Emerald, The False Sacrifice of White, 2017, p. 4.

2.

Yully Yoon, “Invitation Text,” same publication, p. 2.

3.

Luce Irigaray, translated by Eunmin Lee, “Women on the Market,” in This

Sex Which Is Not One, Dongmunseon, 2000, p. 230.

4.

Gayle Rubin, translated by Hyesoo Shin, Okhee Lim, Hyeyoung Cho, and Yoon Heo,

“The Traffic in Women,” in Deviation, Hyunsilmunhwa, 2015, p. 110.

5.

Luce Irigaray, This Sex Which Is Not One, ibid., p. 232.

6.

Boma Pak, “Acknowledge Abstraction – Material, Volume, Mood, Filter,

Reduction,” Webzine SEMINAR (Issue 8), 2021.

http://www.zineseminar.com/wp/issue08/pakboma/

7.

Luce Irigaray, This Sex Which Is Not One, ibid., p. 233.

8.

Dark matter is a form of matter that is widely distributed throughout the

universe and interacts with neither light nor electromagnetic waves, but

possesses mass. Areas with concentrated dark matter disturb the motion of

nearby stars and galaxies through gravitational effects based on Einstein’s

general theory of relativity, and even bend the path of light.

Dark matter is estimated to make up about 22% of the universe’s total energy.

The rest consists of observable matter and dark energy. Considering only matter,

dark matter is believed to comprise 84.5% of all matter in the universe—far

exceeding that of visible matter.

(See: Wikipedia, “Dark Matter”)

9.

Mladen Dolar, translated by Sungmin Lee, The Dark Point, B Publishing,

2004. I first encountered this book through Boma Pak.

10.

Ibid., p. 161.