The

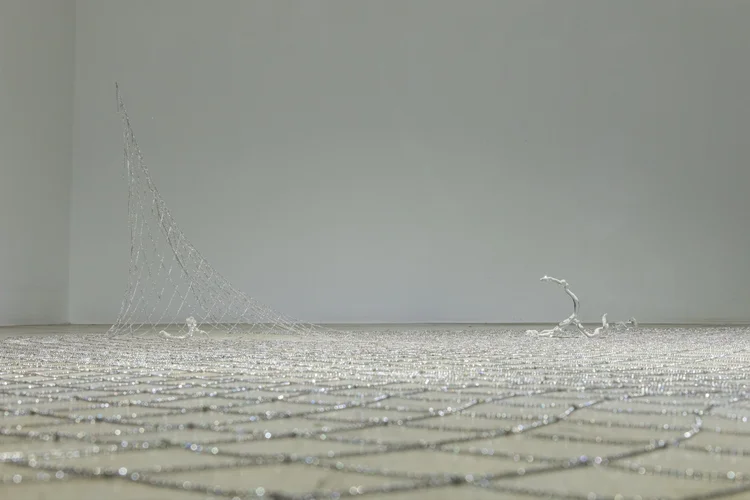

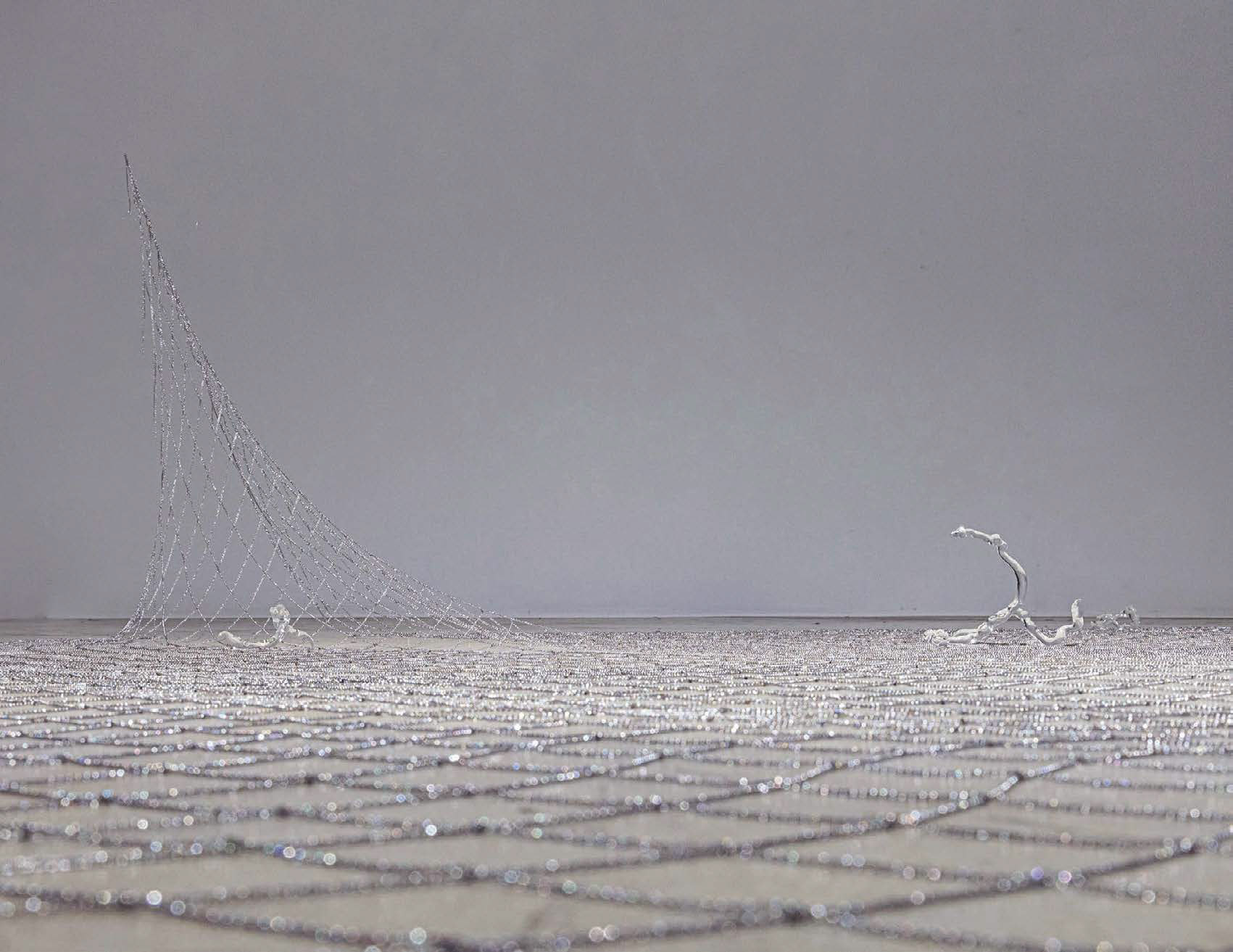

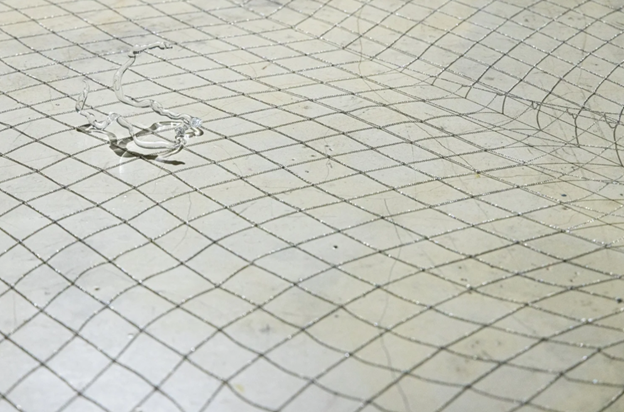

following year, Cho expanded the Nudi Hallucination series

into a new work titled Altered Fluid, imagining a

species that emerges and survives in the aftermath of Earth’s destruction.

Assuming the existence of post-human life forms, she replaces their flesh and

bones with glass and metal materials, presenting them as future biotic

sculptures. In environments with differing temperatures, they become

semi-fluid, able to move as if their seals have been broken. Considering that

Cho has consistently created her sculptures through melting and solidifying

glass and metal, this fictional supposition blends seamlessly into her

worldview.

The

flesh of the future, having replaced protein, is an invented attribute. As if

recalling evolutionary history, these creatures resemble but are not identical

to prehistoric life forms—they are no longer defined by human knowledge or

intelligence. They are birthed with new brains, different genetic codes, and

other trajectories of evolution.

Omyo

Cho imagines beings that don’t exist in the world, traces of memory that have

slipped through the mesh of time. And in this journey—where vanished memories

and unarrived futures seem to exchange places—we find ourselves already

participating.

1.

Georges Chapouthier, What Is an Animal?, Hwanggeumgaji,

2006, pp. 24–25.

2.

Cho-yeop Kim, “The Greenhouse at the End,” in 2nd Korean Science

Fiction Award Winners Anthology, Hubble, 2018, pp. 9–60.

3.

Young-ha Kim, Goodbye, Human, Bokbok Books, 2022.

4.

Omyo Cho, Traces of the Unmentioned, Matter and Immateriality,

2018.

5.

Ibid., p. 103.

6.

Pogni Kim, “Art Must Engage with Social Issues,” The Hankyoreh, July 2,

2020.

7.

Omyo Cho, excerpt from artist note for 《Jumbo Shrimp》, 2021.

8.

Ibid.

9.

Omyo Cho, artist note, 2021.

10.

Exhibition organized as part of 《Artist View of Science 2022: The Artist's Perspective on Science》, co-hosted by the Surim Cultural Foundation and Korea Institute of

Science and Technology (KIST).

11.

Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” October, vol. 8, 1977,

pp. 30–44.

12.

Omyo Cho, “Memory Searcher,” unpublished manuscript, 2022.