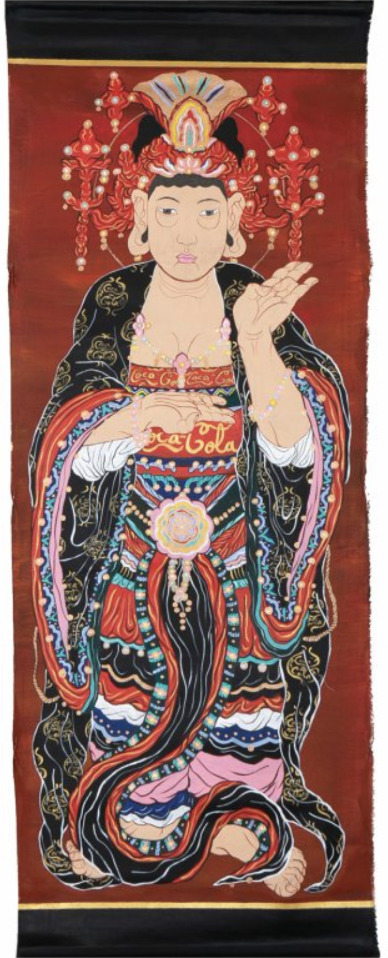

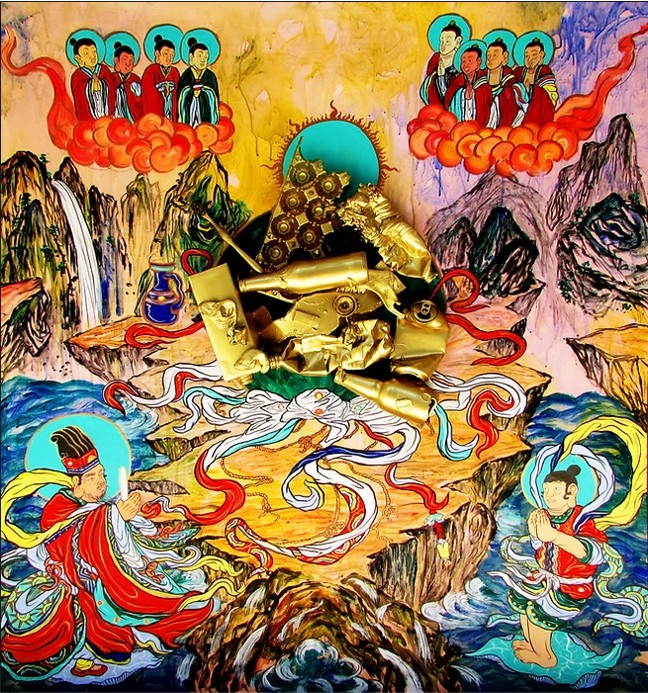

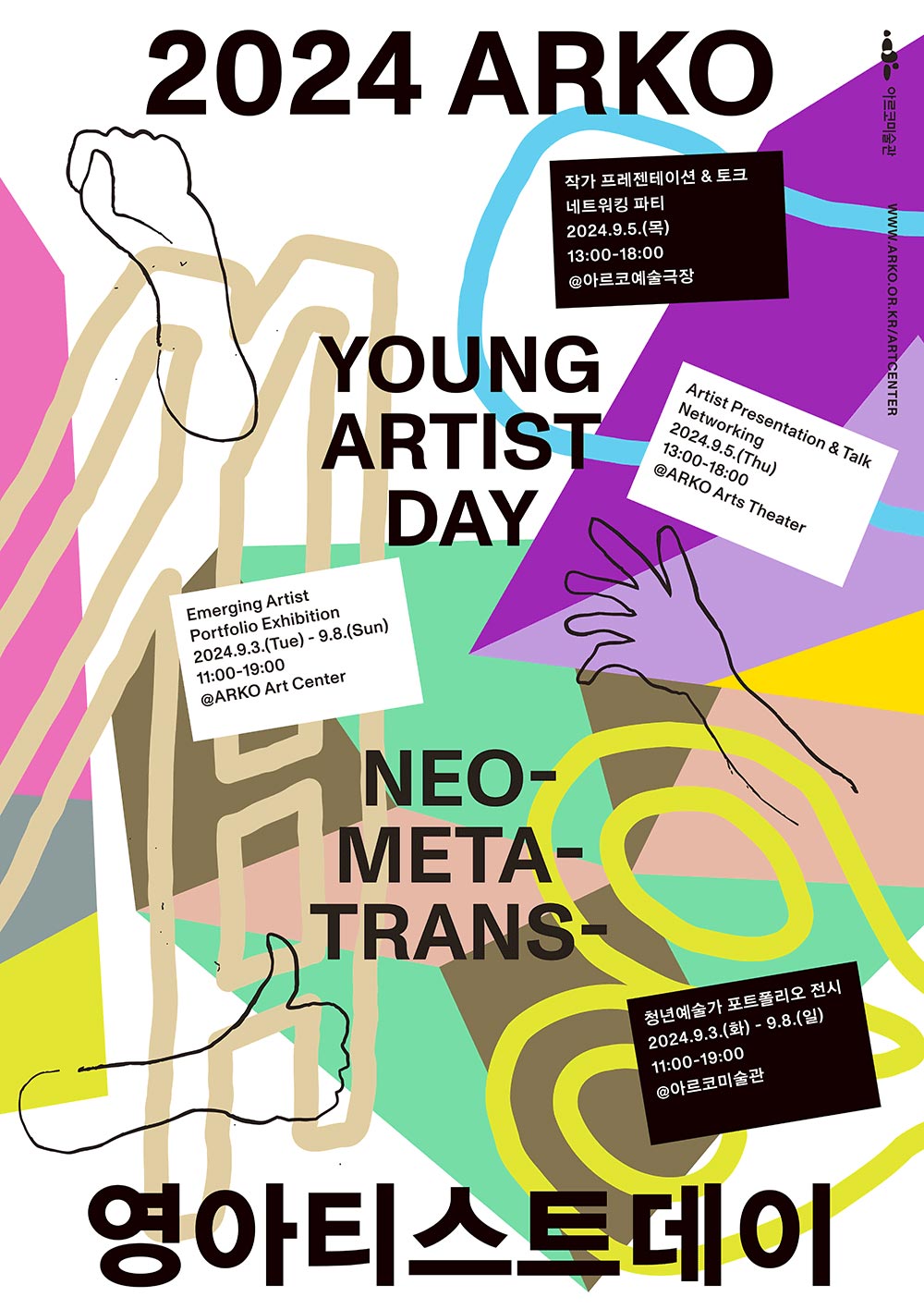

Chi calls 《The Way of the

108 Gods》 a space for religious “play,” where

portraits, scriptures, and rituals generate an aura of transcendence. During

the exhibition, Sahng-up Gallery becomes both an “altar” for 108 deities and a

“playground” for spectators' speculative imagination. The artist invites

audiences into this fictional cosmology. Like ceremonial music, The

Way of the 108 Gods Music (2023) flows calmly, while the slow,

fluid movements in The Way of the 108 Gods Dance (2023)

extend the doctrine beyond the visual into the auditory and tactile. Melodies

fill the space; the masked figure moves wordlessly; 108 portraits flutter.

Everything is interconnected in an organic whole.

The grammar of traditional religion, when activated, shakes our

temporal consciousness. Recognizing that time itself is a constructed notion

allows us to think beyond past, present, and future. Chi’s installation—a

spatiotemporal environment filled with portraits, scriptures, and

rituals—provides viewers with cues for timeless contemplation. In the heart of

bustling Seoul, this shared “religious play” between artist and audience takes

on a voluntary, delightful, fair, and sensorial form.

The word “道 (do)” in 《The Way of the 108 Gods》 refers to the “way”

or “path.” This exhibition is but one of many paths toward happiness that Chi

proposes. Rather than articulating his enlightenment directly, he hints at it

through metaphor—through unfamiliar expressions and sounds, simply offering the

possibility of a path.

“As I exhale, a mysterious smoke stretches far. Though the smoke

soon vanishes, it remains forever in the heart of one who has seen it. That

which is invisible does not mean it does not exist—such is the way of the Dao.”— Marlboro (#79)

Chi’s mode of play is like a fleeting puff of smoke—appearing and

disappearing in a moment. And yet, he hopes that when audiences return to their

everyday lives, they will perceive the world as an object of free observation

and joyful engagement. Leaning on familiar names like Coca-Cola, Starbucks, and

Chanel, he continues to pose fundamental questions.

— Written by Koeun Choi (Independent Curator)

1. The project began in 2020 with the work Cosmic

Gods (2020), which deified four global brands—Coca-Cola,

Starbucks, McDonald’s, and Campbell’s Soup—and was exhibited in DOPA

+ Project: The Cosmic Race (Palacio de la Autonomía, Mexico). In

his 2022 solo exhibition The Way of the Gods (Samgaksan

Citizen’s Hall, Korea), he presented 25 deity portraits. This current

exhibition unveils the completed The Way of the 108 Gods.

2. Among them, Deity No. 71—Philips—begins its scripture with the

phrase “bushy and overgrown.” While the author of this text was reminded of a

blender upon seeing the brand name “Philips,” the artist’s association appears

to have led instead to an electric shaver. Or perhaps, the deity was not

derived from the Philips brand at all but from a razor placed near the artist’s

bathroom sink. Rethinking everyday things often hinges on numerous

variables—such as nationality, gender, age, and living conditions. Acknowledging

these limitations, the artist began by looking closely at what was physically

closest to him.

3. The video begins with the countdown “Cinco, cuatro, tres, dos”

in Spanish, followed by a traditional Eastern religious dance.

4. A masked figure in a long white robe performs a religious

ritual inside a department store.

5. For example, traditional masked dance in Korea typically

features exaggeration, satire, and narrative parody. In contrast, the movements

in The Way of the 108 Gods Dance depart from these

conventions, marking a different affective register.