The Rationality of the Coca-Cola Goddess Ritual and the

Imagination of a Subjective Future

“What

distinguishes fiction from everyday experience is not a lack of reality but an

excess of rationality.”

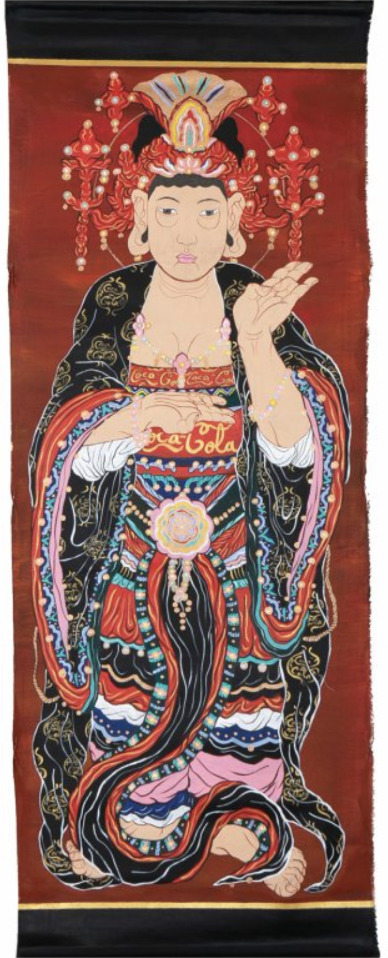

The

birth of a Coca-Cola goddess in the context of Korean traditional shamanism and

religion—if this isn’t the most outrageous fiction, what is? Minseok Chi has

been shaping 108 brands symbolizing contemporary consumer culture into

traditional Korean deities. He invents new characters for each god, and these

deities are expressed through inscribing metaphors onto symbolic terrains that

determine the visibility of states of objects. Among these invented deities,

the Coca-Cola goddess goes beyond myth to form a religion, with the concretized

ritual 〈Ritual en honor a la Diosa

Coca-Cola〉 listing the philosophy of community

through “mediation.” Chi orchestrates a gut (shamanic ritual) that filters

incompatible agents—Coca-Cola and Korean shamanism—diagnoses the hypothetical

context (event) they belong to, and assesses the coexistence and continuity of

heterogeneity, identifying aspects of validity and alterity. He then invites us

into a form that is both perceptible and thinkable within visual art.

Chi’s

incompatible agents are at once sacred by necessity and commercial and secular,

and also sacred beyond the commercial and secular—they represent a laborious

process of erasing differences situated at their margins. This derives from the

artist’s core value of mediation. The fictive world of Minseok Chi, 〈Ritual en honor a la Diosa Coca-Cola〉, is

not a space revealing fiction’s lack of reality within mythological context,

but rather a stage exposing the excessive rationality underlying the world we

perceive. Through the fictive Coca-Cola goddess myth, I trace both the inside

and outside edges of history’s margins in order to examine the meanings and

forms of alternative futurism taken by the Coca-Cola myth.

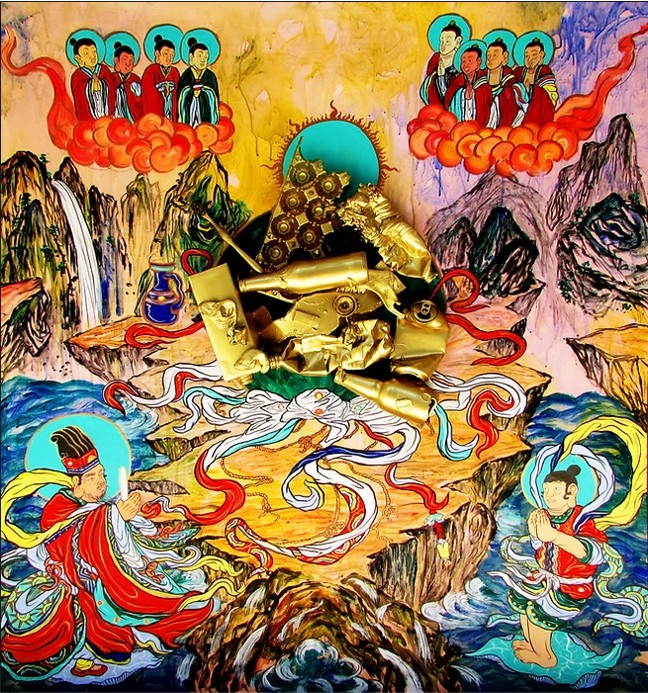

The

Coca-Cola goddess is born from charcoal during an era when the sun has grown so

enormous that the world burns and people can no longer open their eyes. She

offers her black shadow to the blind, allowing humanity to see and find its

path. That the goddess is born from charcoal—a substance that shares attributes

with the sun she opposes—ties into the “identification phenomenon” found

frequently in myths. This phenomenon occurs when a mythological character

possesses the same attributes or shape as the adversary. Athena of Greek

mythology, for example, bore Medusa’s severed head on her shield; in the Indian

epic Mahabharata, the hero Arjuna and his archrival Karna were born of the

same mother and both excelled at archery; even in the Harry Potter series,

the protagonist shares a soul connection with Voldemort and both speak

Parseltongue. Such stories reveal the mythical logic that humans, in their

unconscious, are drawn to continuously gaze upon the object of their hatred.

In

the Coca-Cola goddess myth, we also find interpretations of the number 3, which

carries significant weight in mythology. According to Georges Dumézil’s

“trifunctional hypothesis,” society is upheld by three hierarchical functions:

“sacredness” (magic and ruling power), “combativeness” (physical force and

victory in war), and “abundance” (wealth, beauty, and love). The myth includes

three key elements: “charcoal,” a “gourd bottle,” and a “herring with

legs”—each aligning with these functions. The dual nature of the charcoal, from

which the goddess is born, represents sacredness. The gourd bottle, filled with

a dark energy opposing the sun, represents combativeness. The herring with

legs, always at the goddess’s side, represents abundance as it travels between

water and land, and like charcoal, carries sacredness, while also referencing

its abundance as a major food source.

Charcoal

possesses the dual nature of emitting light and heat like the sun while

retaining a cold materiality. This duality mediates between heat and cold,

serving as a bridge between divine and human realms, yin and yang, light and

darkness. In mythology, an image missing one foot is often used to signify

mediation. Likewise, the fact that the Coca-Cola goddess, born from charcoal,

becomes lame after being struck by stones thrown by people further emphasizes

her mediating role. Such motifs of mediation appear in many fictions:

Cinderella, who cleaned ashes from the hearth; the Polyjuice Potion or Ministry

of Magic fireplaces in Harry Potter—these symbols all reflect

transformation via marginal substances.

Eventually,

the Coca-Cola goddess, who had shared her cooling aura with humans, sacrifices

herself to block the ever-intensifying sun. She ascends to the heavens,

scattering the dark energy from her gourd bottle across the sky. The sun and

the war-god who opposed her encounter new mediation, resulting in a cycle where

they appear in the sky only once a day. When people saw the darkened sky, they

exclaimed, “Look!”—and thus, night was born. This linguistic magic reflects

sympathetic magic through language. “To see” is “to know.” As is well-known,

the English word “see” and the French word “savoir” (to know) derive from

“voir” (to see) and “avoir” (to have). Seeing is possessing, is knowing, is

power. In the myth, humanity reclaims subjectivity by seeing, owning, and

understanding the night.

Minseok

Chi’s world is not a singular one. For him, the world is not defined by values

decided through majority rule or shaped by colossal agents like capital or

power. The world he observes is one of polarized value bias, capitalist

inversion of meaning, forgetfulness, and alienation. That’s why he calls for

mediation and for the subjective comprehension of the world. In his mythology,

the recovery of subjectivity through mediation is central and recurrent.

The

colossal sun symbolizes both the essential element for life and absolute power.

In the Coca-Cola goddess myth, the endlessly growing sun becomes a condition

leading humanity toward suffering. This expanding sun symbolizes the Western

metaphysical ideal of purity and clarity of consciousness without distractions.

In contrast, Coca-Cola—resisting this great sun—embodies a duality that

includes Western reason and capitalism. By drawing this symbol of capitalism

into the realm of Korean shamanism, Chi subverts the Western universal

appropriation of Korean culture—the gaze that sees Korea as a mysterious and

exotic small Eastern nation to be studied or solved.

Minseok

Chi states, “Art is a new kind of play that can dismantle the serious play

surrounding us.” He becomes the master of a fictive play that entangles

contradictory and heterogeneous concepts, dismantling binary oppositions. He

fully appropriates and interprets enormous systems—economic and cultural—that

surround him. He challenges the dominant gaze toward Korean traditions and

reclaims them through his own lens. In other words, his act of absorbing

Coca-Cola into traditional culture is both humorous and serious: drinking a

refreshing Coke under a massive sun and contemplating the remaining Coke bottle

shaped like a gourd. Through this, Chi asks: What is our real life? How should

we live? His alternative imagination, born of self-reflective questioning,

becomes a subjective act of creation by someone who lives in a hybrid culture

between East and West.