Standing

with brush, ink, and paper—the traditional media of East Asian painting—Cha

Hyeonwook may appear to stand apart from the dazzling visual combativeness that

defines the forefront of contemporary art, with its emphasis on speed and

competitiveness. For Cha, still in his twenties, the long-debated and

unresolved discourse surrounding the “identity of Korean painting” is more a

tiresome and alien landscape than a burning issue; a controversy that has been

repeating itself for decades without resolution. At the center of this aged

debate lie strong criticisms of the formulaic repetition of ink painting

traditions and the complacency of art education at universities, both of which

have failed to respond adequately to contemporary realities and sensibilities.

Meanwhile,

generational shifts in the art scene and changes in the broader artistic

environment—such as the fostering of emerging artists and the art market boom

since around 2007—have led to the abandonment of brush-and-ink traditions. Many

artists now pursue formal experimentation through various new media, or attempt

to adapt traditional East Asian painting to contemporary sensibilities. Such

efforts are no longer new.

Cha

Hyeonwook began within the framework of ink landscape painting, but now seeks

to transcend that framework to reveal landscape as a perceptual emergence.

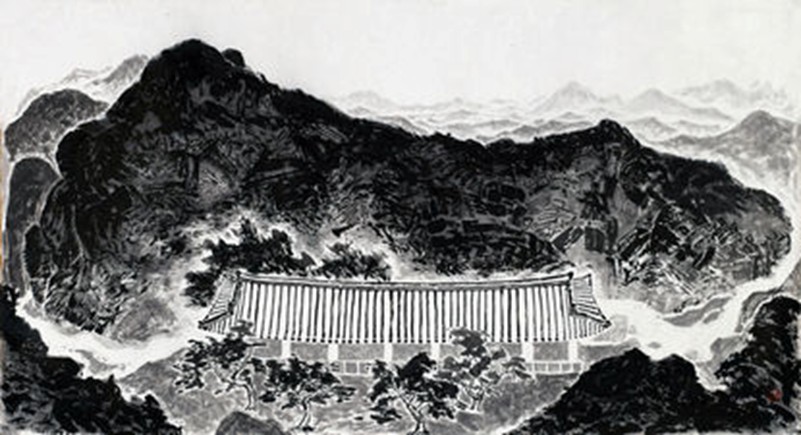

Comparing his 2011 series Drawn and Carved: The Story of

Byeongsan with the 2013 series Drawn and Carved

Stories offers insight into how and where he began to break away

from the conventions of true-view landscape painting. In the

earlier Byeongsan works, he continued the spatial

composition typical of traditional landscape, prominently employing bird’s-eye

perspective and partially integrating level-distance perspective. Peaks viewed

from a high vantage point opposite Byeongsan, distant ridges behind the main

peak devoid of realism, lower foreground ridges, and the flatness of the

watchtower columns seen from the front—all form dramatic contrasts with the

sharply sloped roof of the pavilion and ornamental trees in the courtyard, as

well as with the river, now stripped of its physical force and reduced to

symbolic presence. These works combine elements of traditional style with

subtle experimental attempts.

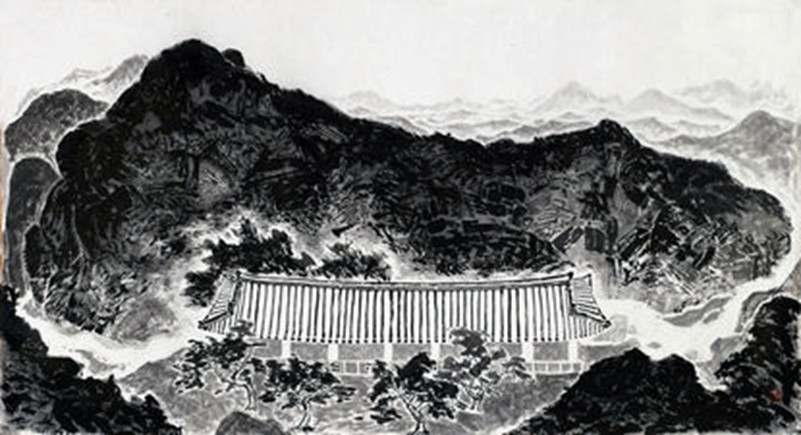

In

the subsequent works of the Byeongsan series that

he continued over time, the viewer’s attention is drawn more toward the diverse

depictions of the landscapes surrounding Byeongsan, seen across from the stably

rendered Mandaeru pavilion. Although the symbolic tone has been removed, the

deliberately meandering river encircles Byeongsan like an island, forming a

self-contained world, separate from its surrounding scenery. Here, Byeongsan no

longer appears as a singular, unified space fixed from one perspective;

instead, disparate scenes acquired through shifting viewpoints coexist without

tension or conflict, together forming a harmonious vision of the mountain.

Perhaps

what unfolds is not one continuous image, but a kind of pictorial folding

screen, composed of glimpses of the actual mountain observed from various

points in Mandaeru, interwoven with the artist’s unconscious, memories, and

learned mental image of the mountain. In the

final Byeongsan work, the physical vantage point

of Mandaeru disappears completely, and what emerges is a mountain not inside

nor outside—a perceptual construct whose subject matter and viewpoint are both

ambiguous. The act of gazing upon Byeongsan, and the temporal specificity that

once surrounded it, vanish. What remains is a point of engagement between the

present object and the perceiving body.

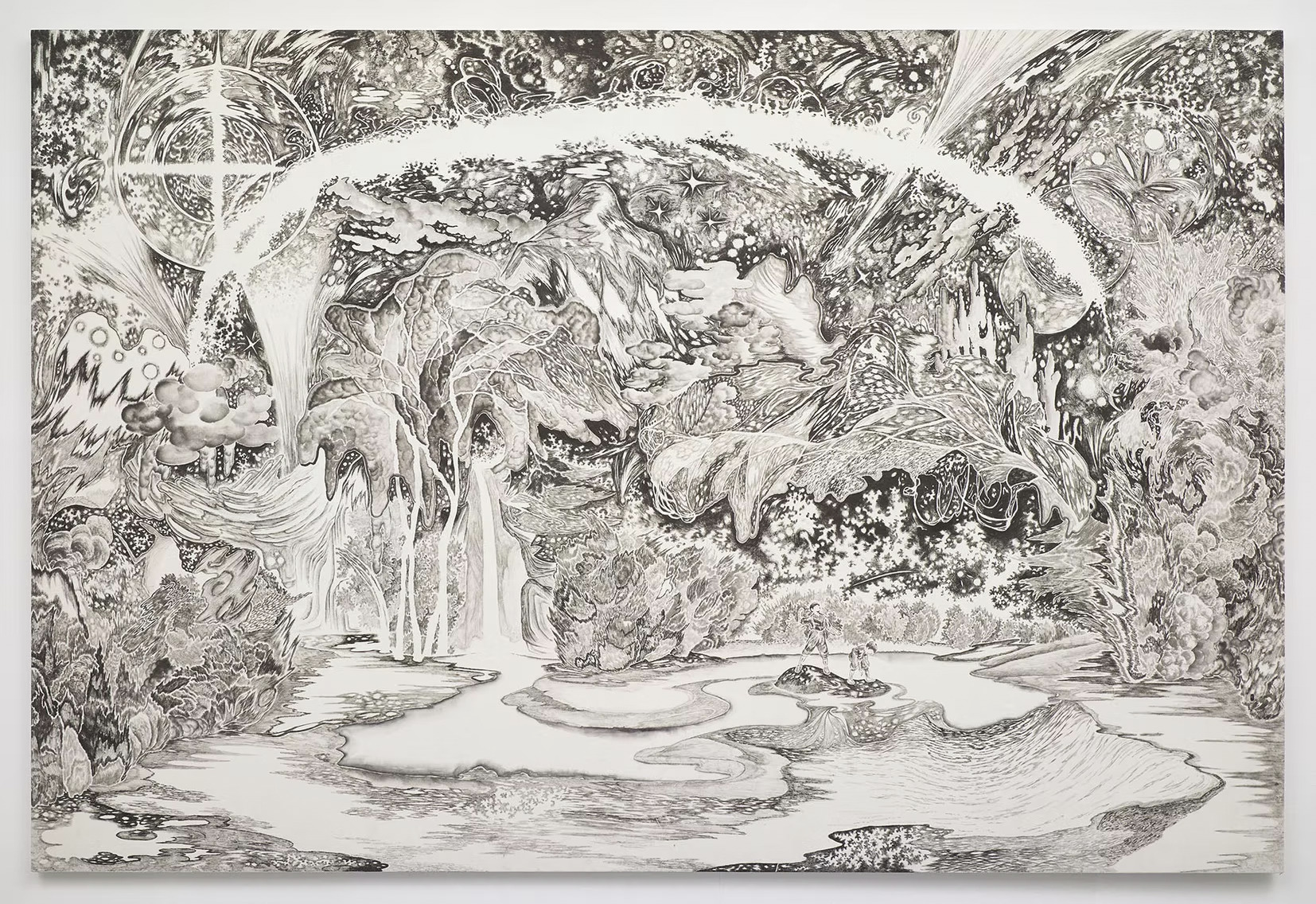

In

his 2013 Eye & Mind series, although the works

do not fully abandon depiction, they can be considered non-representational in

the sense that they visualize the process of the artist’s bodily engagement and

reaction to the object. Maurice Merleau-Ponty stated that perceptual experience

becomes possible when the subject halts their everyday way of looking. The

vision he calls "embodied vision" arises only after suspending or

pausing the traditional and habitual gaze shaped by science and knowledge. Accordingly,

Cha Hyeonwook attempts to convey a process in which a world not easily visible

through visual perception surfaces on the plane of perception as it intersects

with the body’s sensitivity—what he calls "resonance."

From

him, we do not see realism rooted in retinal recognition, but rather a realism

of attitude—of one who seeks to reveal what cannot be seen. His is a gaze and

observation that conveys patience, memory of the body, and the desire to make

the invisible visible.

Wherever

the brush passes, lines and areas of unpainted white emerge, and the various

flows of brushstrokes and irregular traces that fill these white spaces seem to

be projections and imprints of “resonance” and “reverberation” for the

artist—guiding the viewer into an open realm of visual perception. The subject

Cha observes and investigates is nature in its imperfect state: one in which

the boundary between the seer and the seen can intersect, reverse, consume each

other, or even reject one another. In this sense, his works invite the viewer

into an ambiguous state—where it is unclear whether the object is perceiving

him, or he is perceiving the object.

The

viewer, too, may fluidly participate in the experience, depending on their own

circumstances. The gaze of the Other is free to enter and exit at will, from

any point. The world he describes does not present objects directly before the

audience, but instead becomes a repository of rich experience, offering a

glimpse of a reality that does not exhaust itself. This gives the impression

that the process and depth of cognitive perception and expression are

ceaselessly ongoing.

Cha

Hyeonwook’s aspirations are twofold. One is to explore and realize the

universal potential of painting using brush, ink, and paper—the medium he

cherishes and wishes to handle most effectively. The other is to have his

paintings seen simply as "paintings," free from the prejudices tied

to traditional media. These wishes stem from a dual crisis: both the pressure

on painting’s position within contemporary art and the general indifference and

lack of understanding toward traditional media. Like many of his predecessors

in art history, he is likely to continue wandering and swaying along the

boundary between optimism and skepticism.

Even

so, we cannot reject the subtle allure, the healing and subversive power held

within the mystery of the pictorial rectangle. Within that rectangle, we always

expect the silent contemplation and unrestrained interpretation of a

first-person narrator.