The

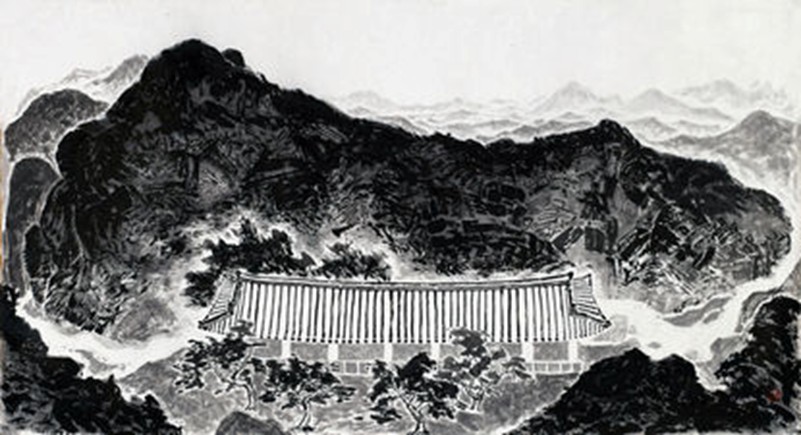

first impression I had upon encountering Cha Hyeonwook’s work was a surface

filled with ink. There’s certainly a resemblance to traditional landscape

painting, but this is quickly followed by the impression that it’s difficult to

detect any traditional techniques or motifs. Only upon closer inspection does

one begin to notice traces of traditional techniques and subject matter

scattered throughout the work. There are also some signs of borrowing from or

studying old paintings. The entire surface evokes a massive mountainous

structure reminiscent of the Travelers Among Mountains and

Streams by Fan Kuan of the Northern Song dynasty. The

composition that draws the eye upward toward the sky, or the bird’s-eye

placement of water at the lower portion of the painting, are also traces of

traditional landscape painting. But that’s about it. It offers nothing more.

The

surfaces he devotes himself to seem to resist the temptation to depict or

represent objects. “Language, only when it gives up the expression of the

object itself, can truly be considered speech.”¹ Description that does not

replicate is closer to ambiguity that touches upon the various potentialities

of things, rather than a regulated conceptual language.

Perhaps

because of this ambiguity, his work is slippery to read.

Following

the ink tones that dominate his canvas, one encounters marks that seem like

surfaces when seen as lines, and traces when read as planes. Yet to call these

mere accumulations of ink would be misleading, for they are highly figurative.

The representations of rocky masses reminiscent of landscapes show states of

ink saturation that could be called accumulations, but they are not structured

through such accumulation. While clearly repainted multiple times, the result

is too flat and lacks the density required to qualify as built-up ink layering.

If

this were a traditional landscape painting, one would expect to see

compositional logic such as upward-looking (angshi), bird’s-eye (bugam), or

level-distance (pyeongwon) perspective. But that is not the case here. The

impressions of mountain peaks or riverbanks at the bottom of the canvas are at

most minimal suggestions or clues for interpretation, not metonymic signifiers

to be read as landscape. In this sense, his understanding of landscape seems

less rooted in experiencing real scenery and more akin to acquiring landscape

as a language. It is close to dismantling or reconstructing the landscape

through conceptual inference, rather than perceiving it as a spatial domain.

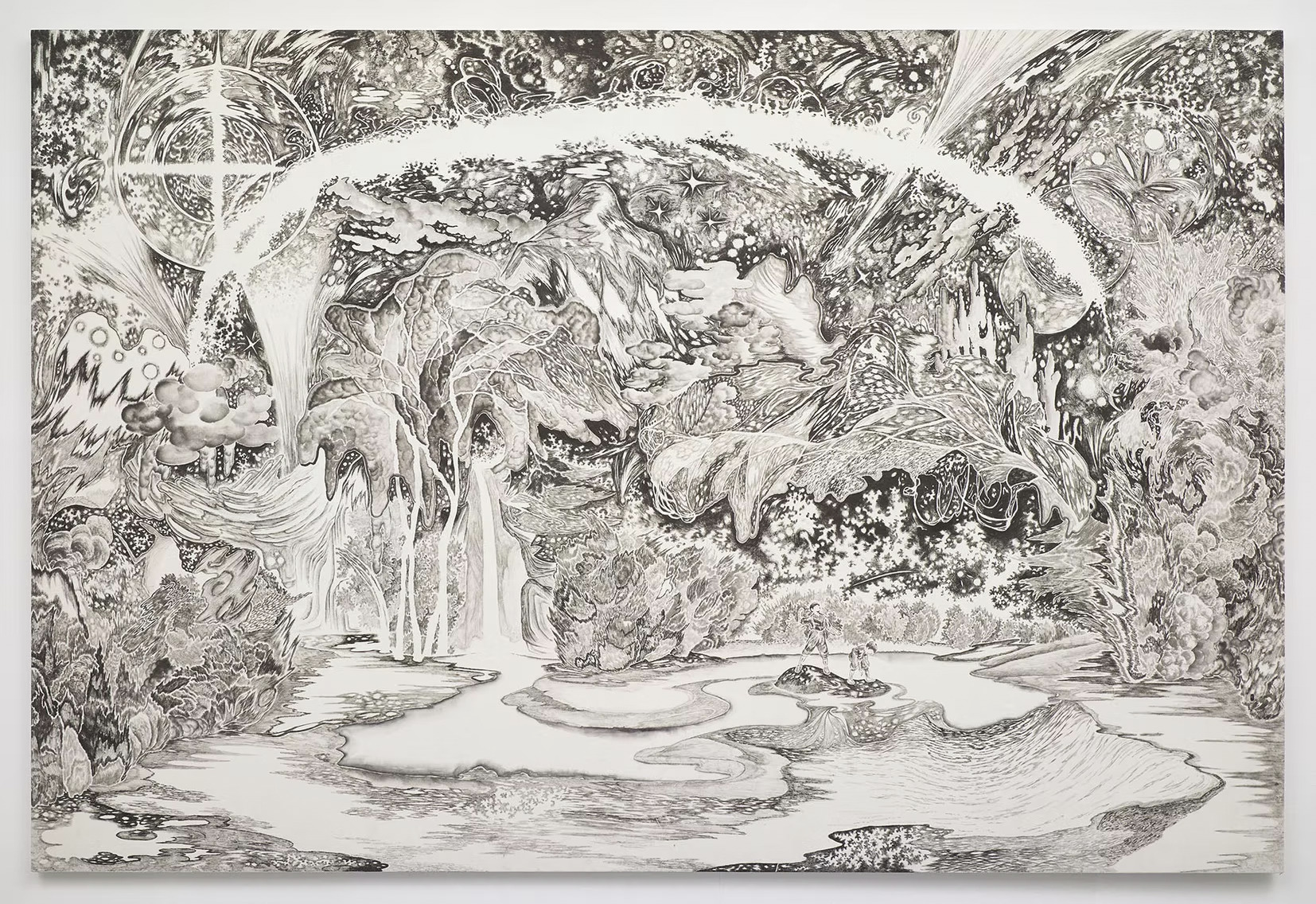

When

examining some of his unfinished works, one can observe how a landscape starts

to take shape, only to dissolve mid-way as ink traces take over. The images

recede, and the ink marks linger as gestures in motion. Rather than

constructing landscape painting as a montage, these traces hesitate and delay

the formation of form, acting as smudged ink that leans toward dissolution. The

impression that emerges—of a transition from form to formlessness, from

tradition to de-tradition, from flatness to figuration, from ink to blackness,

and from line to plane—stems from here.

The

traces of ink—his ink tones or the sequences of strokes that compose the ink—do

not depict forms but rather exclude them and, to a certain extent, restrain

them, thereby advancing toward disintegration. However, this is not entirely

deconstructive, but rather a state in which potentiality is left intact. Even

when he leaves the lower edge of the canvas white and sparsely arranges ink

marks, it is difficult to view this as a composition intended to depict rocks

or stream banks. While such associations cannot be entirely denied, these

merely serve to structure the white space, presenting the presence of water and

sky. This structure functions, in part, as a point of distinction from the

full-surface treatment of Western painting. Without the white margins at the

top and bottom, the work would readily be read as a type of abstraction

characterized by all-over composition, and the technique of using ink marks

would not easily escape appropriation from Abstract Expressionism.

However,

these features do not appear to reflect a conscious effort or understanding of

the juncture between the contemporary and the traditional. Rather, it seems he

adopts certain elements of tradition as aesthetic positions or as methods of

structuring and conceptualizing his work. This may be why, even while pursuing

modernization, he cannot completely discard the compositional strength of

tradition in one sweep.

In

some of his works, the uneven texture of the collaged backgrounds functions as

a latent force that interrupts ink, line, and movement, preparing for a new

kind of motion. The absorbent quality of Korean paper naturally accepts lines

and ink, but the ridges and seams of attached paper fragments hinder, restrain,

and disrupt this flow at unexpected moments. They create dissonance rather than

harmony. “Strictly speaking, the unrepresentable resides in the impossibility

of a particular experience being expressed in its own distinct language.”² This

is why I have described his work as a deconstruction of traditional landscape

painting.

It

is a method of escaping depiction and representation, and at times functions to

block the artist’s intervention. It creates movement led by chance across the

surface. The aggregation or parallel arrangement of traces—fragmented into

movement, time, and gesture—does not compose the image but flattens it,

directing the viewer’s gaze toward the deconstruction of time. These are not

forms structured by time, but movements that have been flattened, liberating

the image from specific representations of landscapes. The white space and

representational character of the surface become the only points of connection

with reality. These characteristics shift the work away from depiction and

representation, toward movement and deconstruction, or toward new ink landscapes

as movement itself; they guide the viewer toward landscape as gesture, toward

abstraction as surface, and toward a surface effect of modernization departing

from traditional ideas.

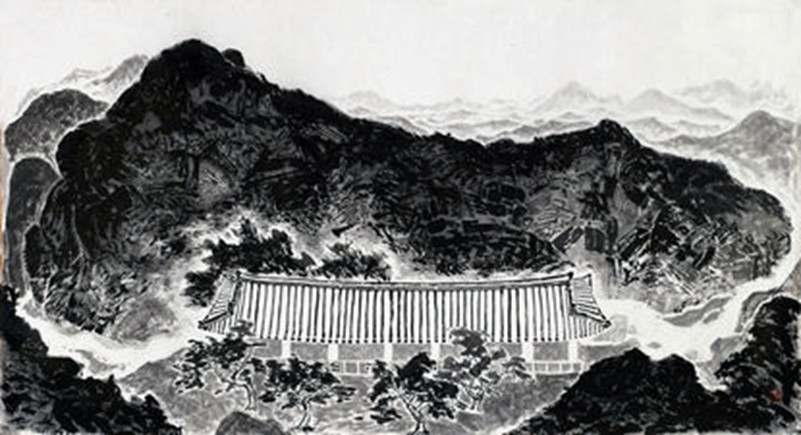

This

guided perspective of his does not lead to concrete forms but to disassembled

traces. While the overall impression may be entrusted to general notions of

mountains or water, the absence of specific depictions—of what mountain or what

water—suggests the work is closer to conceptual understanding or presentation.

It only reaffirms the word “mountain.” In this regard, his work is rich in

conceptual elements and reveals characteristics of ideational landscape

painting. The configuration of forms composed of ink marks that come together

and disperse fills the entire surface, and this association with the

understanding of conceptual landscape painting stems from such a context.

Nevertheless,

the issue is that the characteristics seen in his work are, in fact, familiar

techniques and familiar landscapes. These are forms that have already been

attempted by various artists under the aim of modernizing Korean painting, and

his work exists within that very context.

It

is at this point that he must ask questions about the properties of ink as a

material—ink as an autonomous element—and about his own choices. If his use of

ink aligns with the traditional sense of the medium, then he must ask what that

choice of ink truly means. If he is employing ink as a material through which

tradition is used to implode tradition itself, then he must ask what this

deconstruction entails. The reasons for his use of collage or montage must also

be made clear. If the intention is to deconstruct landscape rather than newly

interpret it through collage or montage as a way of understanding landscape

painting, then a more precise examination of the meeting point of those

elements is necessary. If the purpose of deconstruction is not landscape but

rather the ink itself, then an active inquiry is required—one that approaches

the ink work as a question of fragmented and recombined consciousness, or

interpretation, or as a method of decoding landscape painting.

“Language only gains meaning when it gives up copying thought and is

dismantled, only to be recombined through thought. Just as a footprint reflects

the movement and effort of the body, language carries the meaning of thought.

Therefore, the empirical use of established language and the creative use of

language must be distinguished. Empirical use is merely the result of creative

thought. Parole as empirical language—that is, the use of already established

signs—cannot be considered parole in the true linguistic sense.”³ If tradition

merely acts as a norm for me, we are simply looking at formulaic images, and

things appear as such. In that space, neither individuality nor history can

arise. Nor can we expect an expansion of consciousness toward newness. However,

if tradition is a path of prior understanding for parole, and if it can lead us

to a universal mode of understanding, then tradition will guide us to the

richness of experience.

Rather

than hastily assigning completed meaning or structure to Cha Hyeonwook’s work,

what is more necessary is to recognize the possibilities of movement that it

presents. His landscape or ink-based works do not lack urgency in the questions

they must answer, but the structure with empty top and bottom and tightly

packed left and right becomes a closed space laterally and an open space

vertically—yet one that cannot move. This paradoxical composition of

traditional space, like his attempt to achieve deconstruction of landscape

painting through the irregular textures of collage and montage, allows us to

see his landscape work as one where the natural compositional power given by

traditional placement is interpreted instead as a feature of disassembly. It is

about dismantling and reconstructing an existing language into his own.

And

in that place, we witness a different kind of experience—an impact from latent

languages.

¹

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Indirect Language and the Voices of Silence, trans.

Kim Hwaja, Chaek Sesang, 2005, p. 26.

² Jacques Rancière, The Destiny of Images, trans. Kim Seongwoon, Hyeonsil

Munhwa, 2014, p. 222.

³ Maurice Merleau-Ponty, ibid., pp. 26–27.