"Wait till you’re my age and see. This

country won’t change no matter what you do… I wish adults wouldn't say such

things."1)

This was the headline of an article featuring

interviews with Korean secondary school students serving in the Youth Assembly.

When I read the article some time ago, I was reminded of a conversation I had

with my mother two years ago. We were having coffee at a café when the subject

of the Candlelight Demonstrations (a nationwide movement to oust President Park

Geun-hye from office in 2016 and 2017)2) came up in conversation.

My mother asked me if I went to “those sort

of things” too. Taken aback by the implication of those words, I replied to

her, “Of course I go to those places too, mom. But not every week.” My mother

looked at me with a mixture of compassion and pity in her eyes. She smiled

bitterly. “Do you think [your actions] will change the world?”

I am one of the older members of the

“millennial” generation in Korea—those born between 1980 and 1994. We learned

modern history edited according to the political leanings of whoever was in

power at the time. Our tiger parents drilled us through the fervently

competitive education system to ensure we entered the top universities and

lived more comfortable lives than theirs, but we cannot ever hope to achieve

the same level of economic success as their generation with the Korean economy

in constant depression and with the real estate market plagued with speculative

investments.

While we are adept with technology as either

“digital natives” or “users” and receive the benefit of higher education, we

are also moving out of our familial homes later than preceding generations.

The generation before mine, the generation of

my youngest aunts and uncles, is called the 386 Generation3) or the

Democratization Generation. Before that is the Baby Boomers, my parents’

generation, who spent their adolescent years during the two military

dictatorships. Their parents’ generation, the Silent Generation, acquiesced to

their given fate. Each generation’s knowledge of modern history was shaped by

the political aims of those in power, which is why although I was raised by my

parents, their view of the Candlelight Demonstrations differs from mine.

Of the legacy each generation leaves behind

for the next, some things are meant to be forgotten and relearned. As Korea is

an ethnically homogeneous nation, issues like class conflict and racism are

relatively obscure. However, there clearly are disagreements between the

generations, mainly surrounding the blatant lack of

understanding on gender issues and acceptance of multiracial

families. Korean millennials are now in the process of exposing such issues and

bringing about change.

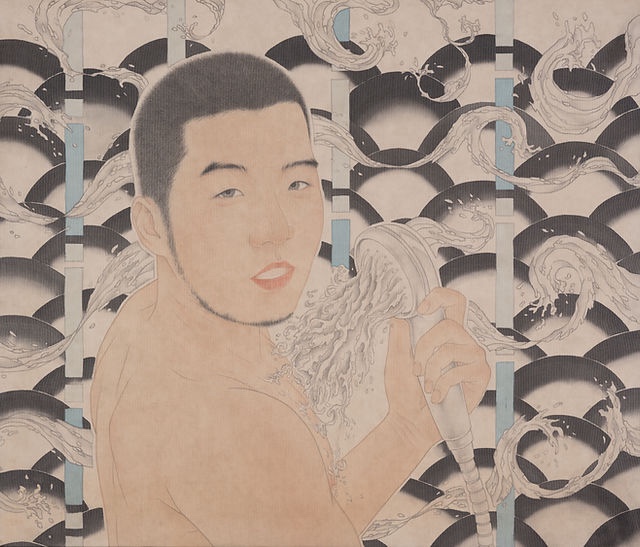

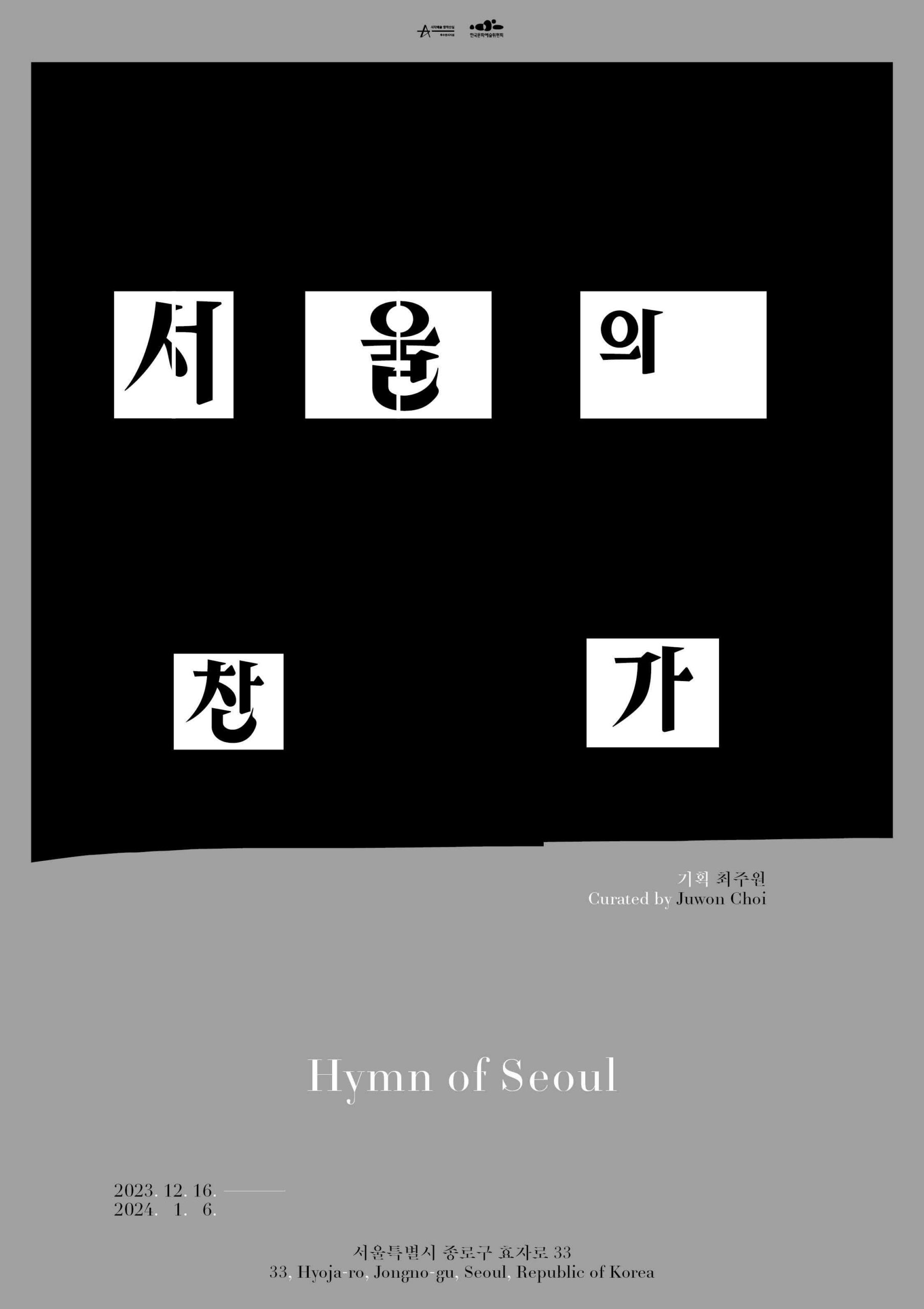

《Flags》 is an exhibition I have built through the process of observing,

interacting with, and studying my family, neighbors, and others in and around

my life: separate generations of a seemingly homogeneous Korean society. The

exhibition begins with the imagery of “flags” hoisted by many individuals and

groups during the Candlelight Demonstrations of 2016 and the responses that

followed thereafter.

The groups represented by the flags during

the protests of 2016 and 2017 went beyond the scope of the usual protesters,

largely comprised of universities, labor unions, and political parties. Such

new flags included the flag of the Green Party, which advocates for

environmental movements, the rainbow flag of the LGBTQ+ community, as well as

countless flags of other civil organizations. Other protesters engaged in a

playful jest using flags by parodying existing organizations.

Flags for the

Korean Confederation of Cat Unions, Rhino Beetle Research Association, Aquarium

Sans Frontiers, and the Federation of Korean Dog Owners were raised. These

flags served as “floating signifiants” (@jangpoongyeon, the Rhino Beetle

Research Association's Twitter account), whose bearers participated in and

contributed to the protests in the context of their respective interests. The

flags they hoisted proclaimed their identity, beliefs, and orientation and

signified the bearers' social coordinates.