The

imagination of self-identity in 《44》 is expressed through a kind of

autobiographical narrative, which seems to be emphasized once again by the

“overlapping” of the artist’s past works and their various relationships. The

most vividly self-conscious image is the aforementioned simhodo. In his

previous work, 〈Shimhodo_Vegabond 尋虎圖_樂流〉(2019), the artist depicted a scene in

which a tiger is born after a bodhisattva stabbed the artist. Here, the artist

juxtaposes the tiger, which he identifies with as an embrace of loss, in a

relationship with another figure (bodhisattva). However, in this solo

exhibition, the figures are nowhere to be seen. Some of the works appear as if

they are posthumous scenes in which the artist/tiger has eliminated the

bodhisattvas around him. Where have the Bodhisattvas gone? What has happened to

the tiger?

In 〈Shimhodo_Chosen 尋虎圖_柬擇〉(2018), the artist/tiger relationship is

situated within and relies heavily on the relationship. In a similar vein, in

his first solo exhibition in 2018, 《Hwarangdo 花郞徒》, the artist drew figures from his surroundings, aspiring to a ‘gay’

image, and at times, he was self-loathing. If we apply the aforementioned dual

structure to the dimension of self-awareness, Park’s fourth solo exhibition, 《44》, can be understood as a reconsideration

of the past iconography through which he recognized and identified himself

within relationships. In other words, the tiger on the screen of 《44》, where the bodhisattvas have

disappeared, is a form and iconography that examines itself, not the

relationship with its surroundings, but itself. In the aforementioned 〈Sun play 日劇〉 and 〈Moon

play 月劇〉, the tiger (usually depicted in the form of a

Buddha) wearing a shin-gwang/du-gwang[3] seems to attain the enlightenment of

good behavior in the midst of the different qualities of the outer and inner

world. In today’s world, where all human relationships are theatrical and

dramatic on a curtained stage, the tiger comes across as a symbol of the will

to affirm one’s identity. In the same vein, we can read the images in 〈Zero two 無二〉(2024), where the bodhisattvas

from past works have been erased, leaving only the figures of spears piercing

from above and below, and 〈Tailless 無尾〉(2024), where the figures have disappeared, leaving only the helmet

and trident of Dongjin Bodhisattva.

In

the end, the confrontation, repetition, and rewriting of 《44(Sasa)》 simultaneously pass through “Sasa 師事”, which means to be taught, “Sa 辭”, which

means to refuse, “Sa 死”, which means to die, and “Sa 些”, which refers to something insignificant and small. The very

structure of the exhibition already implies the meaning of reminding us of

something trivial, something private, and the act of erasing something. Perhaps

the exhibition invites us to see not only the individual works, but also the

more distant traditions and the artist’s previous works together in a

three-dimensional relationship, to ‘layer’ what is being repeated and

transformed, and to see what feelings and allusions are being conveyed. The

intertextuality of the exhibition is both a cohesion in which multiple forms,

contents, and narratives are brought together and an expansion in which they

are layered. The relatively large-scale images of 〈Return

回〉(2024) and 〈Wheel 輪〉(2024) in the center of the exhibition, such as the Shimwudo’s “人牛俱忘”[4] iconography, clearly reveal the duality and complexity of

Park’s work throughout the exhibition, as well as its cohesion and expansion.

Stripped of any superficial temporal narrative, or of the events that occurred

between the cow and the herdsman, any relationship in these works, like

Shimwudo’s “人牛俱忘”, offers no basis for interpretation

beyond their simple markings. Such starkly simple images, “self-conscious

scenes that overcome dichotomies such as “beginning and end, inside and

outside, me and the other, past and present, tradition and newness,”

backgrounds and margins support the superimposition and circularity of the

seeker’s journey.

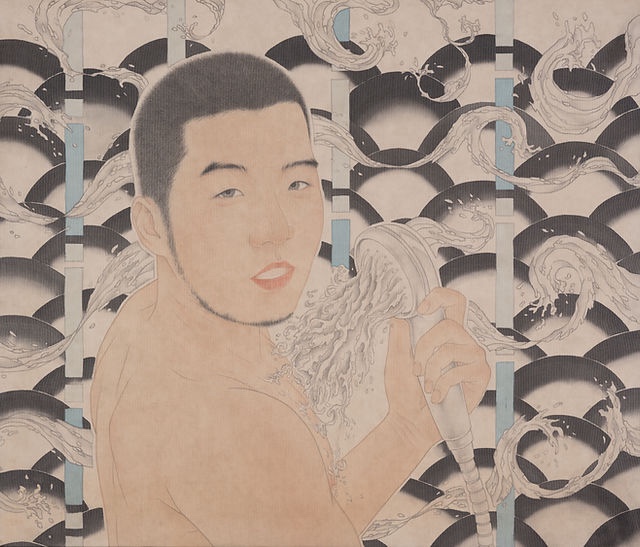

In

〈Enigma 我尾〉(2024), a

self-portrait included in 《44》,

the artist’s figure appears within a gap, or even torn state. This “appearance

as torn state” is a different kind of image than the appearance of the artist

in his surroundings in the aforementioned works such as 〈Shimhodo_Chosen 尋虎圖_柬擇〉(2018) and 〈Shimhodo_Amrita 尋虎圖_不二〉(2021). It’s also a different kind of

personality image than self-loathing and admiring others.

The

facing of the 《44》

can also literally refer to the collective confrontation of the different

elements that make up the artist’s work, such as the Buddhist art tradition,

queer identity, relationships, and past experiences and events. While the work

that traverses different times, experiences, forms, and narratives cannot be

categorized as autobiographical, it is possible to present this solo exhibition

as a sharing and expansion of queer identity and its relationship to the other,

as well as various rituals and forms of thinking about its manifestation. I try

to perceive the seemingly monotonous works with enlarged margins and bland

backgrounds as attempts to confirm, juxtapose, and superimpose their

heterogeneity within a more intimate space-time, or to expand them into an

infinite screen. In this way, I imagine a scene in which the artist’s queer

identity and contemporary narratives are grafted onto the form and content of

Buddhist art, explored anew, overcome, and then confronted and confused again.

Hyukgue

Kwon(Curator)

[1] study under. (The English exhibition title “44” and the

Korean exhibition title “사사四四 ” and all

references to “sasa” in the text are homophones in Korean.)

[2] “A drawing that illustrates the stages of Zen practice using

the analogy of a cow and a child, and is also known as the ten cow drawing

because it has ten stages of practice.”, 「Shimwudo」, 『The

Encyclopedia of Korean National Culture』: https://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Article/E0033873.

[3] head aureole

[4] ‘Both Bull and Self Transcended.’, The eighth of the ten

figures of the Simwudo, “人牛俱忘” depicts

the state of forgetting the cow and then forgetting oneself, and is drawn as an

empty circle. It symbolizes the state before the separation of the subject and

object, that if the object, the cow, is forgotten, the subject, the child,

cannot be established, and only when this state is attained is one said to be

fully enlightened.”, cited above.