00. The Narrative of Artist Grim Park (朴그림, b. 1987) Can Be Largely Summarized in Two Themes

One

is the story of overcoming as a Buddhist painter trained through

apprenticeship, who entered a university department for Buddhist art and

experienced hierarchical discrimination and conflict. The sense of bewilderment

and confusion felt between the academy system—which tends to devalue

apprenticeship education—and the traditional world of master-disciple

relationships narrowed his place in the art world, compelling him to find a new

path in order to survive as a painter.

The

other is the narrative of a queer man born in Jeongeup, North Jeolla Province,

who studied in Gyeongju and later encountered cultural barriers and conflicts

within Seoul’s gay community. Unlike the identity confusion he experienced as a

gay man during his university years, the alienation and difficulties he

encountered in Seoul led him to critically reflect on the mechanisms of

personal/social identification and strategies of assimilation/differentiation

that queer men navigate. By reinterpreting the narcissism, envy, and desire

present among gay men as a Buddhist artist, he has been weaving new meanings

into both his private and public identities. These narratives are inextricably

linked to his ambiguous position as a contemporary artist.

Ultimately, these two

threads converge into a singular narrative of Grim Park as an artist.

Furthermore, they raise critical questions within the flow of contemporary art:

What place can Buddhist painting occupy in contemporary art? How might Buddhist

painting be reinvented as contemporary art? Thus, Park's work goes far beyond

the scope of autobiographical art.

01. Grim Park

was accepted into the Buddhist Art Department at Dongguk University’s Gyeongju

Campus in 2006 but was unable to enroll due to personal circumstances. For

about half a year, he attended a design college, and from late 2006 to early

2008, he studied sculpture under his high school mentor, sculptor Son

Chang-yeop, while working as an assistant. From 2009 to 2010, he served as a

social service agent as an alternative to military service. In 2012, he entered

the Buddhist Art Department at Dongguk University’s Gyeongju Campus and

graduated in 2016. In April 2017, he relocated to Seoul.

In

2009, he met a Buddhist painter (whose name cannot currently be disclosed) and

began learning traditional painting through apprenticeship. Encouraged by this

mentor, he pursued formal education in Buddhist art, but since 2016, he has

been outside of that master-disciple relationship.

(Note: In his first year at university, in 2012, he won a special prize at the

Seorabeol Art Exhibition.)

Starting

with the creation of Lotus Altar Painting at

Okcheon Temple in Yeongdeok in 2015, and Mother Kṣitigarbha Bodhisattva (produced in 2016) at Eungsin

Hermitage in Gwangyang in 2017, he began his independent path as a painter.

With that, he also started his life in his 30s in Seoul and made a determined

choice to forge a new path as a contemporary artist, even formally changing his

name.

(Other

major records of Buddhist painting production include:

2017: Solitary Sage Painting at Gaeseong Hermitage

in Uijeongbu;

2018: Willow Avalokiteśvara at Muam Temple in Jecheon;

Water-Moon Avalokiteśvara at Bohyeon Temple in Bucheon;

Mountain Spirit Painting at

Bodeok Hermitage in Seoul;

Fierce Tiger Painting at

Hyeonmyeo Hermitage in Sancheong.)

He

began gaining attention in the contemporary art world with his first solo

exhibition Hwarangdo – Men as Beautiful as

Flowers (April 6–14, 2018, Bulil Art Museum Hall 1 at

Beopryeonsa Temple). That same year, he won the ABSOLUT ARTIST AWARDS, and has

since actively participated in a variety of projects, including the group

exhibition Flags (2019, Doosan Gallery New York)

and the two-person exhibition Male Forms: Hwa-hyeon Kim and Grim

Park (2020).

Through

his second solo exhibition CHAM: The

Masquerade (April 21–May 29, 2021, YOU ART SPACE), artist Grim

Park finally began to critically respond to the way he had been interpreted in

major media outlets—namely, as someone applying and reinventing traditional

painting within contemporary contexts. This exhibition marks his first

exploration in which he poses and reflects on his own plastic identity as a

modern painter.

-01. Even

though the Joseon royal court outwardly upheld a policy of promoting

Confucianism and suppressing Buddhism, the current of Buddhist art steadily

continued, with uniquely Joseon styles and conventions emerging, such as

the Sweet Dew Paintings (Gamro Taenghwa). Whether

created by individual painters or by groups of monk-painters led by principal

monks and editors, these works can clearly be traced through the recorded

painting inscriptions (hwa-gi, 畵記). However,

during the modernization process of the late modern and contemporary eras, as

Western concepts of art were introduced and hybrid educational systems mixing

Japanese, Korean, and Western styles (wa-seon-yang, 和鮮洋)

took root, Buddhist art was relegated to the realm of the vernacular, outside

the academy system.

Awareness

of this marginalization began to rise in the late 1960s, following the

normalization of diplomatic relations between Korea and Japan in 1965 and the

subsequent push for industrialization. To prevent the extinction of traditional

skills related to temple painting, Buddhist sculpture, and temple architecture,

the Ministry of Culture and Public Information and the Cultural Heritage

Administration began discussing the establishment of a Buddhist art department

in universities in 1968. This led to the founding of the Buddhist Art

Department within the College of Buddhist Studies at Dongguk University in

1971. As a newly established department offering government scholarships, the

university expressed pride, stating that it was launching a department that

should already exist in a national university.

Since

the department’s founding mission was to preserve tradition and transmission

techniques, it did not lead to the modernization or contemporization of

Buddhist art. Moreover, conflicts and frictions with apprenticeship-based

training outside the university system emerged early on and persisted for

decades. (This binary conflict structure between academia and vernacular

tradition has continued even after the Cultural Heritage Administration

established the Korea National University of Cultural Heritage in 2000, which

was reorganized into a university in 2011.)

As

early as 1935–1936, the sculptor Kim Bok-jin (1901–1940), in his mid-thirties,

attempted to develop a new path for modern and contemporary art rooted in Silla

tradition through his studies and production of Buddhist sculpture. In 1938,

the painter Jeong Jong-yeo (1914–1984), in his mid-twenties, produced a

modern Large Hanging Painting (gwaebul) for

Uigoksa Temple in Jinju. These were significant pioneering efforts, but the

momentum was soon lost. Artists who defected to the North could not pursue

Buddhist art under the socialist regime of North Korea, and artists in South

Korea largely ignored the challenging path of engaging with Buddhist art as a

means of entering modernity.

The

rare exception was Park Saeng-kwang (1904–1985), who from 1977 began developing

a new style of modern Korean painting based on Buddhist imagery such

as non-paintings (muhwa). Amid the rediscovery of

traditional culture sparked by the touring exhibition Five

Thousand Years of Korean Art in Japan in 1976, Park freed

himself from the stigma of being a “Japanized painter inheriting the new

Japanese style.” However, his accomplishments only indirectly influenced a few

Minjung art (people’s art) practitioners, and no one explicitly took up the

unfinished task he left behind.

Thus,

experiments to extract the stylistic and structural logic of Buddhist painting

from its medieval formal system and reintegrate them within pluralistic spatial

frameworks—then imbue that with Baroque dynamism, and finally deconstruct and

reinvent it in a contemporary or contemporaneous context—were never even

recognized as valid artistic endeavors. Sporadic attempts to modernize

the Sweet Dew Painting format or create

contemporary transformations of similar Buddhist paintings often resulted in awkward

and clumsy outcomes.

To

put it simply, Kim Bok-jin was a sculptor who believed that one could achieve a

Renaissance-like artistic leap by using Unified Silla Buddhist sculpture as a

benchmark. Therefore, when he was selected in a five-person competition

(including the monk-painter Ilseop) to restore the main Buddha statue at

Geumsansa Temple on Moaksan Mountain in 1935, and the winning piece exhibited a

fairly modern character, it reflected the zeitgeist of the time—hoping to

resurrect national identity from the ruins of Silla.

If

the colonial-era dream of a Renaissance-like cultural revival rooted in

Buddhist painting and sculpture had been more broadly realized, what kinds of

achievements might it have yielded?

Though

there are no “ifs” in history, let us imagine alternate possibilities:

—What if Jeong Jong-yeo or Kim Yong-jun had not defected to the North and

instead stayed in South Korea, advocating for a national contemporary art

rooted not only in Confucian literati tradition but also in Buddhist and

shamanistic practices?

—What if Chang Bal, who led the Seoul National University College of Fine Arts

until the fall of the Jang Myeon–Yun Bo-seon administration, had been a

Buddhist believer rather than a Catholic?

—What if a modern art movement inspired by Cheondogyo had emerged?

—What if a Buddhist ink abstraction movement comparable to the neo-Confucian

Moklimhoe had taken shape?

—What if a contemporary Korean art movement based on Taoist or shamanistic

worldviews were to develop? What would those experiments look like?

Architectural

works like the National Museum of Korea designed by Kang Bong-jin (1966–1972),

the Sejong Center for the Performing Arts by Eom Deok-mun (1973–1978), and the

Ho-Am Art Museum by Samoo Architects & Engineers (1975–1978)—though derided

and mocked by the Korean architectural community—cannot be dismissed merely as

grotesque artifacts born of regime competition with North Korea. Rather, these

buildings and the art and craft objects housed within them embodied the

lingering dreams of colonial-era Koreans who sought to revive the essence of

Unified Silla to forge a better national modernity. (Note: The bas-relief of

the flying celestial being at the Sejong Center, modeled after the Emile Bell,

was a masterwork by sculptor Kim Young-jung.)

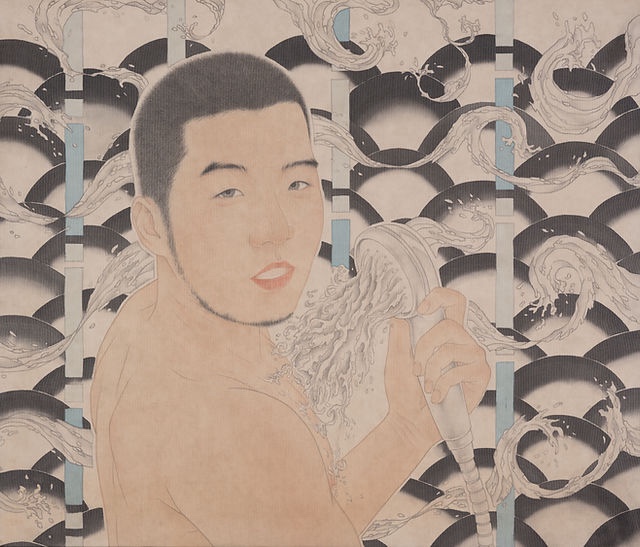

02. Grim

Park’s first solo exhibition, Hwarangdo, had—by the

standards of the contemporary art world—certain aspects that made it resemble

an “Insadong-style” exhibition, meaning it didn’t clearly appear to be a

contemporary art exhibition. As a gay/male/painter who began to capture the

narcissism of gay men expressed on social media using the visual language of

traditional Buddhist painting, it’s difficult to say that Grim Park had a clear

self-awareness as a contemporary artist at that point. However, despite the

modest scale of the exhibition, it conveyed a problematic tension that is rare

even in contemporary art shows that try hard to impress.

Park

held a dual identity as a traditional Buddhist painter and a vernacular

contemporary artist. Having trained in both an apprenticeship system and formal

university education, he possessed the capacity of a painter-craftsman

(hwajang, 畫匠) skilled in rendering

traditional Buddhist iconography such as Goryeo Buddhist paintings. Yet, he had

also been observing how gay men showcased their sexual beauty on social media

and, since 2015, began producing experimental portrait series of gay men.

Though

he used photographic images as references to create portraits, he restructured

the iconography based on his own interpretation. In some cases, the results

became subtly psychoanalytical critiques. His artist statement read like a

direct confession, yet still contained layers of allegory and polysemy.

“Just

like everyone else in the world, I came to use SNS. Within it, I encountered

countless beautiful people. All of them, with confident expressions and poses,

attracted attention and flaunted their beauty. / I envied their self-love. They

became objects of longing for me, and I wanted to make their beauty—what I

lacked—my own through my painting. This is how I began to work on male beauty.

/ I portrayed them using the material I handle best. I captured their beauty

with subtle coloring on fine silk. I believed that the soft and sensitive

nature of silk resonated with their beauty. The effort of layering pigment

dozens of times to achieve color seemed to align with the truth that ‘the

pursuit of beauty requires just as much struggle,’ and that’s why I chose this

method.”

Each

portrait contained a hidden backstory or foreshadowing. While such details were

excluded from this review out of respect for personal privacy, the artist’s

interpretations of each subject were embedded in every work. In some,

traditional patterns were arranged with care; in others, such motifs were

juxtaposed symbolically. Some portraits featured elements like flamingos or

digital camouflage patterns inspired by military uniforms.

The

artist deployed two types of analogies in his critique. One was to identify the

Buddha—who achieved enlightenment by overcoming Mara (Māra, the demon who hinders one’s path to Buddhahood)—as the ultimate narcissist. In doing so, and drawing on the

Buddhist teaching that anyone can attain enlightenment, he considered today’s gay Narcissuses through both

their positive expressions of self-love and the negative manifestations of

self-hatred. He saw the flood of self-loathing among social media users as a form

of interference by Mara.

The

second analogy, based on the first, involved identifying gay men on

“Gaysbook”—a nickname for a gay-specific network on Facebook—as modern-day

Hwarang (flower youths), who both positively expressed their narcissism and

compulsively promoted their looks to gain recognition from others. These

“Gaysbook gays,” caught in a paradoxical state of simultaneously wanting

visibility to fulfill desire and happiness while also wanting to hide from a

heteronormative society, were called forth by the artist as enlightened beings,

as the Hwarangdo of our times.

(The

dictionary definition of “Hwarang” includes the following:

1.

A youth training organization in Silla, composed of well-born, scholarly, and

good-looking individuals with the ideals of cultivating mind and body and

leading society;

2.

The leader of the Hwarang;

3.

A group of entertainers similar to jesters, known for their festive attire,

dancing, and merrymaking, often the male consorts of shamans.)

The

fact that Grim Park’s solo exhibition was held at the Bulil Art Museum, run by

Beopryeonsa Temple, allowed for a meaningful reading of the connection between

the artist’s background—he uses the art name Jeongwol (井月)—and the new body of work. In short,

the Hwarangdo series could be interpreted as

Buddhist paintings, or conversely, existing Buddhist paintings could be

reinterpreted through a queer lens. Until now, no gay artist in Korea or abroad

had attempted to appropriate the queer aspects of traditional Buddhist painting

to reinvent it into a form of queer contemporary painting.

Another

point to consider is the inclusiveness of Buddhism. Even though there was

special support from Venerable Yeo-seo, chief curator of Bulil Art Museum, the

fact that this exhibition took place without a single protest at a

temple-affiliated museum in Korea is remarkable. (Had it been at a Christian

church, exhibiting a series of gay portraits filled with seductive gazes would

have been extremely difficult.)

03. Since Grim

Park began exploring the dilemmas of queer subjectivity through iconographic

reinterpretation based on the grammar of Buddhist painting, he has worked to

develop his own stylistic idiom and iconographic structure.

In

the 2018 work Seeking the Tiger – Selection (尋虎圖―揀擇), Park responds to the

traditional Buddhist painting Seeking the Ox (尋牛圖) and weaves new queer iconography and

allegory. Seeking the Ox (also

called Ten Oxherding Pictures) is a Zen Buddhist visual

metaphor for the process of finding one’s true nature, comprising ten stages of

spiritual development. However, in Park’s version, the animal symbolizing

enlightenment is not an ox, but a tiger.

The

cute and pretty baby tiger, painted in a somewhat folk-art manner, appears

repeatedly in his work and is interpreted as the artist’s persona.

In Seeking the Tiger – Selection, the tiger held by two

beautiful young gay Bodhisattvas who illuminate the meaning of life becomes a

symbol of the artist’s own artistic journey. (The figure on the left drapes the

tiger in a six-colored rainbow veil.)

In

the 2019 painting Seeking the Tiger – Falling Stream (심호도 – 낙류), one young gay Bodhisattva

is shown trying to stab the other with a knife. The rainbow-colored ritual vase

clearly refers to the queer world, but what does the crane motif embroidered on

the cloth that wraps around the body of the figure in peril (possibly

symbolizing a crisis of love?) signify? While the crane is one of the ten

symbols of longevity, when contrasted with the tiger, it can also represent the

scholar-official, the refined literati.

(The

white crane motif had previously appeared in one of

the Hwarangdo series paintings, I

SLAY [2016].)

In

any case, within the conflict between the two gay Bodhisattvas, the tiger sets

off on a new journey, floating atop a lotus petal. Before the tiger bloom white

orchids, which in ancient Greece symbolized virility, in the Victorian era

wealth, and in contemporary times hope and purity.

By

contrast, in the 2020 work Bel Ami, the artist reveals

his desire to break away from previous visual grammar. He attempts to visually

strip away the "Buddhist colors" that had come to define his identity

as a "queer artist who uses the forms and techniques of Buddhist

art." Within a square format borrowed from Instagram’s interface, Park

paints a group of nude gay men engaging in a variety of erotic poses.

The

title Bel Ami first refers to a gay porn label,

but secondarily evokes the protagonist of Maupassant’s novel Bel-Ami—a man

who uses his beauty to fulfill his ambitions—and thirdly, quite literally means

“beautiful gay friends,” referencing the narcissistic gay youths depicted in

the earlier Hwarangdo series.

Each

figure is connected by a sheer black fabric that partially conceals their

genitals. According to the artist, this cloth is analogous to the veils (sara, 紗羅) traditionally worn by Bodhisattvas in Buddhist paintings. This

sacralization of erotic imagery through “sacred veiling” attempts to create a

form of aesthetic sublimity—extracting noble value from a sexual network that

might otherwise be dismissed as vulgar. In other words, it is a pursuit of new

harmony between the sacred and the profane.

In

terms of form, Bel Ami can be seen as an effort to

render the human body, typically confined within the medieval iconographic

system of Buddhist painting, more freely within a Renaissance-like visual

order. Park has mentioned wanting to try a neoclassical nude group painting in

the style of William-Adolphe Bouguereau. With this in mind, comparisons can be

drawn to works such as Combat I & II (1928)

from Grande Composition by Tsuguharu Foujita, or

to Military Immortals (군선도) (2017) by Hwa-hyun Kim, who sought to respond to

Foujita’s iconic “milky white” skin tones for Asians.

04. In his

second solo exhibition CHAM: The Masquerade, Grim Park

prepares and signals a transition to the next phase of his work. The title

“CHAM” was taken from the Tibetan Buddhist ritual mask dance, which is

performed to expel disease, ward off misfortune in communities and villages,

and bring good harvests. Accordingly, Park suggests that the masked play of

identity among gay men may be sublimated into a kind of purification ritual.

(Since

it is said that Korea’s Cheoyongmu dance was

influenced by the Tibetan cham, it is also interesting to reinterpret the

exhibition title as Cheoyongmu.)

Using

an “equal sign” composition, the upper part of each work features a close-up of

the eyes of men known as “Gaysbook stars,” while the lower part displays motifs

representing the characters and temperaments of the depicted individuals.

The

18-piece MSQ (Masquerade) series, which

self-references the Hwarangdo series, exudes a

darker, more ominous tone than his previous works. Though the same eyes are

depicted, they appear empty, as if devoid of self-assurance. Consequently, the

ornamental patterns once bestowed upon the figures in

the Hwarangdo series now invite a new

interpretation.

For

example, the new work MSQ49548, derived

from Portrait of a Boy (2018), which portrayed a

well-known go-go boy, features new Buddhist-inspired iconography composed of

flamingos and leather straps, conveying semiotic messages. Amid the coexistence

of feminine qualities and masculine strength, the artist captures the resolve

of a figure who reshapes and refines his identity through sheer will.

(The

protagonist of this painting once commented that he works out “like a damn

beast,” and thus the “damn” intensity can be read in his eyes.)

(Note: Since the Hwarangdo series originally

consisted of 18 works, the MSQ series was also

planned as 18 pieces.)

Alongside

the MSQ series, a ceramic sculpture of a baby

tiger titled Hogu and the earlier

painting Bel Ami were also exhibited. However, the

true centerpiece of the show was Bihu, constructed

using the same “equal sign” format.

One

painting shows the eyes of a baby tiger, while the other depicts its tail and a

veil (sara) leaping across it, foretelling a future narrative and temporal

unfolding. In the tiger skin pattern—rendered using the six-fold line technique

typically reserved for depicting human skin—an anthropomorphic personality

emerges. The two golden eyes reflect both mischief and the aura of

enlightenment.

The

artist explained that the Buddha’s eyes consist of five types:

1.

The physical eye (육안, eye of the

flesh);

2.

The divine eye (천안, which

perceives minute details and the future from the heavens);

3.

The wisdom eye (혜안, which sees

through illusions and penetrates universal truths);

4.

The Dharma eye (법안, which

illuminates all things through the light of truth);

5.

The Buddha eye (불안, the eye of

the cosmic creator).

Thus,

the tiger’s eyes are symbols of these five stages of awakening.

Meanwhile,

the white curl between the tiger’s brows (the urna, or “white hair mark,”

baekhosang) is rendered as a black ring, suggesting it may transform into

various forms in the future.

And

the veil (sara) leaping over the tiger’s tail signifies Indra’s Net (Indrajāla), the vast web that stretches above the palace of Śakra (Indra), the king of the gods who presides over the Buddhist

Desire Realm (욕계, yulgye). The metaphor

describes a boundless net, with a jewel at each node. Every jewel reflects all

others, and each reflected image reflects again into every other, creating a

universe of infinite interconnection.

Considering

that Indra’s Net symbolizes the Dharmadhātu of Unimpeded Interpenetration of All Phenomena (사사무애법계), it embodies a

worldview where all phenomena arise in mutual interdependence, each seamlessly

penetrating the others (원융상즉, perfect

interpenetration). In this light, the characters

of Hwarangdo and their eyes become the beads of

this web of connection. Therefore, Grim Park’s new works may be seen as a

contemporary Dharma Wheel (법륜) — a manifestation of the Buddhist teaching that all beings are

infinitely interconnected.

The

artist also remarked that this solo exhibition, which focuses on the eyes of

gay men and baby tigers, was conceived as a kind of Eye-Opening

Ceremony (점안식). This

ritual—also known as the Opening of the Eyes (개안식)—is performed when a Buddhist statue, painting, mandala, pagoda, or

altar is created or restored, in order to consecrate it and activate its sacred

vow.

In

simpler terms, the ritual transforms an object—whether carved, painted, or

constructed from wood, stone, or paper—into a spiritual entity capable of

emitting divine power. (In Catholicism, this would be akin to priestly

consecration.)

By

orchestrating an encounter between the gaze of the audience and the figures

within the paintings, Grim Park endows the queer subjects—who live with dual

strategies of visibility and invisibility—with a sacred aura and a fetishized

sublimity.

Postscript

1) The planning-stage title for the

18-piece MSQ series

was Set. The numbers attached to each

individual MSQ work are the result of converting

the original titles from the Hwarangdo series into

Unicode.

Postscript

2) In the 2020 work Mimi, Grim Park depicted the white

tiger’s tail as a symbol of “the wounds and love that come through connection,”

and the yellow tiger’s tail as a symbol of “the person who cannot resist him.”

The artist explained that this work was “meant to prompt the viewer to ask

whether, like the connections we form in life—where we hurt and heal each

other—this tail is a strangling wound or a warm embrace.” Accordingly, the

yellow tiger that appears in the new work Bihu becomes

both the artist’s persona and a divine beast representing human vulnerability.

Postscript

3) Regarding the double-sided 2020 painting Master &

Subordinate (주종), the artist

explained, “The raised paw is meant to scratch downward, while the lowered head

symbolizes submission—together they represent dominance (DOM) and submission

(SUB).” This composition can also be interpreted as a mudra or symbolic hand

gesture of the yellow tiger, thus becoming a symbol of a world where submission

becomes dominance, and dominance becomes submission.

Postscript

4) The 2020

works Yaho and Hodu offer

hints for the future development of the Seeking the

Tiger painting world.

Postscript

5) Among contemporary Korean artists hailing from Jeongeup, the notable names

include Yoon Myung-ro (b. 1936) and Chun Soo-chun (1947–2018).