Articles

[Critique] Jongwan Jang in Wonderland

November 24, 2023

Yihyun Parek | Editor of Noblesse

Jongwan

Jang, Mt.Melona, 2023, 227.5×364.3cm © FOUNDRY SEOUL

Jongwan

Jang, Mt.Melona, 2023, 227.5×364.3cm © FOUNDRY SEOUL

The

country Jongwan Jang builds on his canvas is a strange one. According to the

artist, he deals with faith and anxiety toward an ideal world by depicting

scenes of paradise and utopia, but it’s far removed from what one typically

imagines as ideal. It’s more like a strange world that one might fantasize

about when lying in bed, unable to fall asleep. At times, it resembles a sacred

illustration found in a leaflet handed to you by a stranger on the street

saying “Be saved.” It even brings to mind the secular, kitschy paintings often

seen in old barbershops. That’s why it’s hard to immediately grasp the true

identity of Jang’s work.

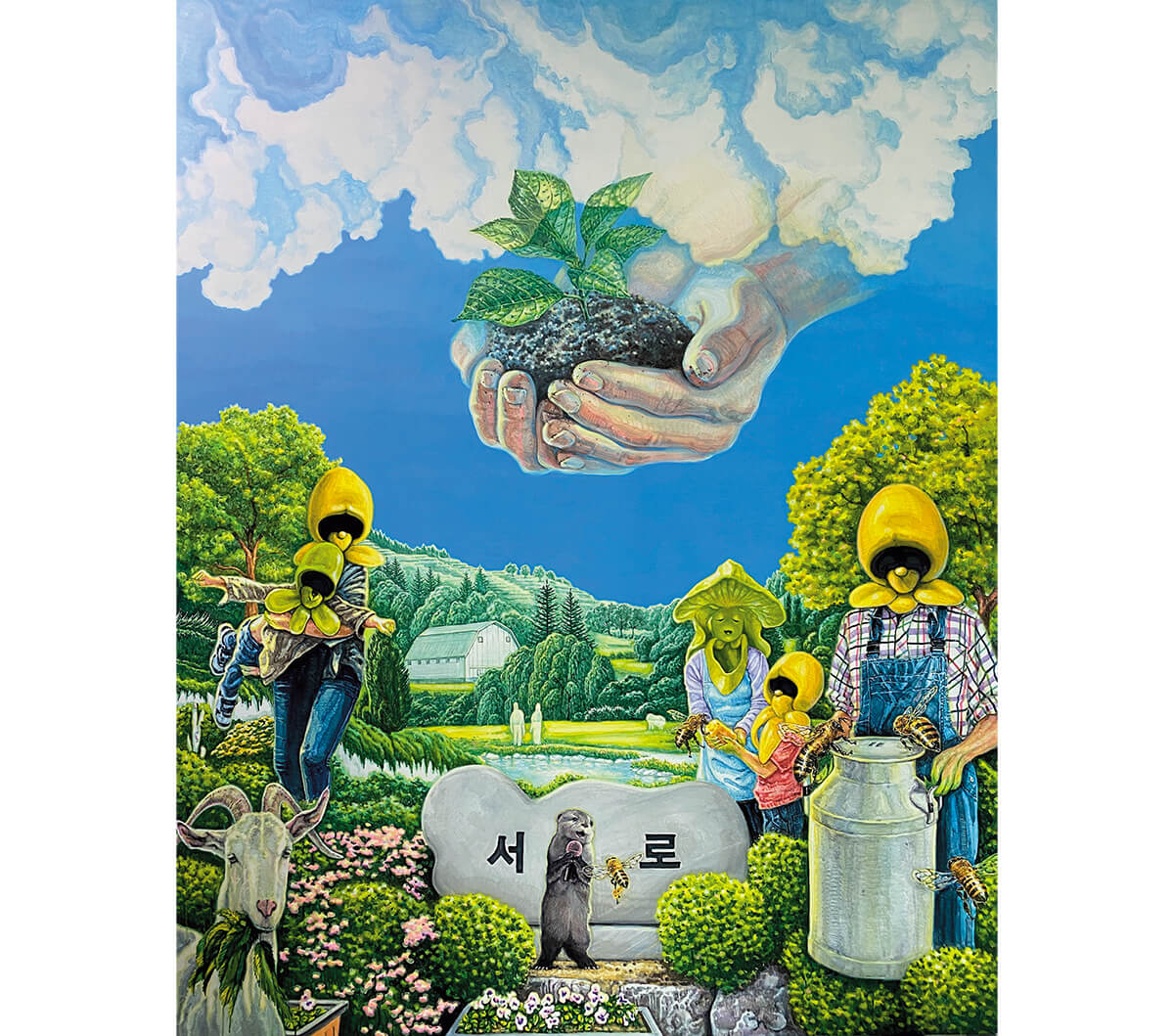

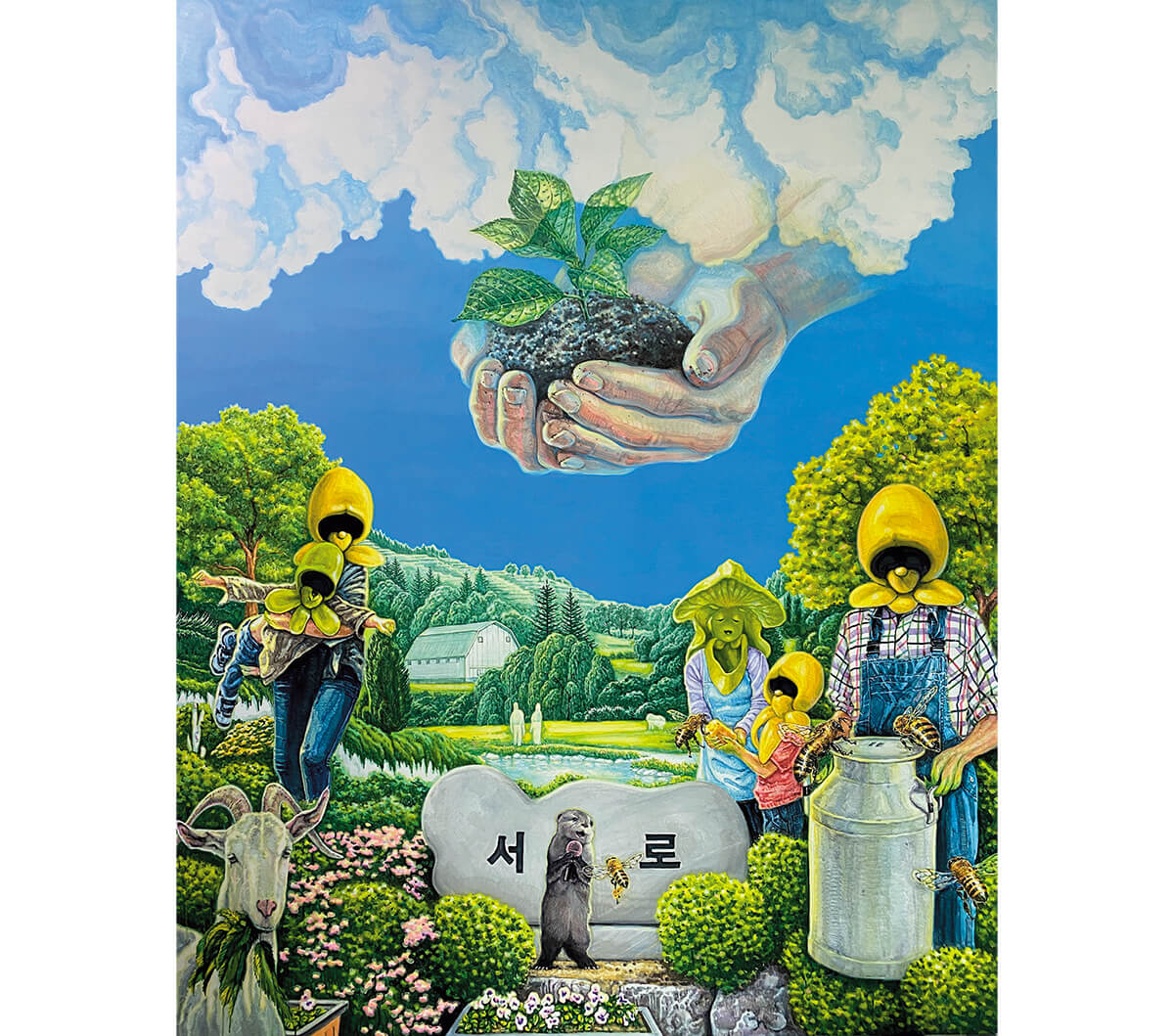

Take Go

West (2023), presented in this solo exhibition, for example.

Sprouts fall from the sky, and everything that lives on the land flowing with

milk and honey appears peaceful. In front of the text “서로 (Together),” otters and bees are seen enjoying dance and music. The

ironic twist is that the word “서로 (Together)”

simultaneously contains “Together” and “Go West.” As is well known, in the

Bible, the west symbolizes the secular and the impure. So what is this work

really trying to convey? I suddenly recall something the artist once said: “I

prefer comedy to tragedy, and absurdist plays to comedy. I believe in the

theory of original evil.”

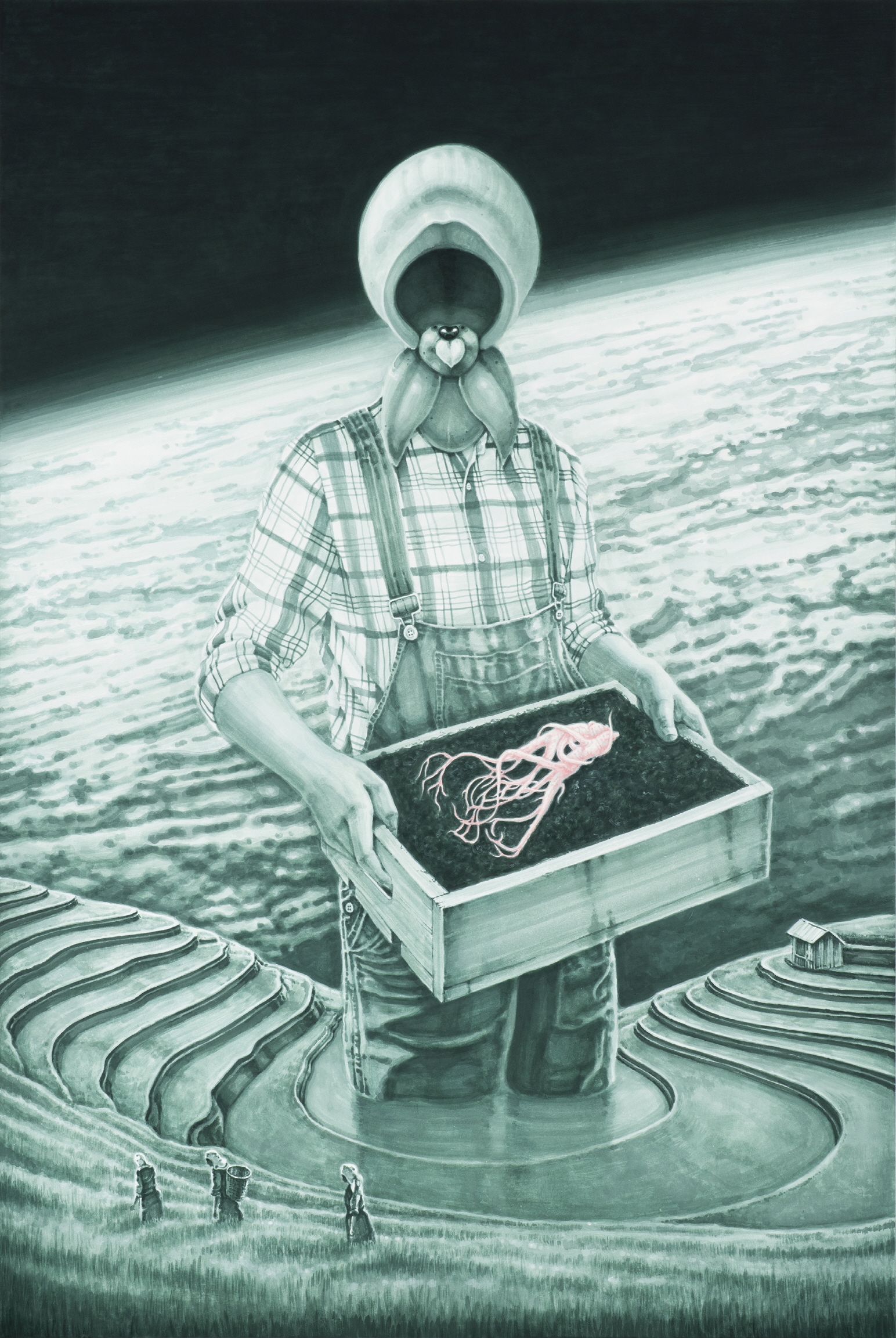

Jongwan

Jang’s solo exhibition at Foundry Seoul is significant in that it presents a

cosmic landscape combining agriculture and futurism (which rejects tradition

and expresses the dynamism of machine civilization as a new beauty). The 30 new

works that make up the exhibition begin with a curiosity: “Is it possible to

evoke a cosmic and futuristic atmosphere not through high-tech objects, but

through pastoral motifs commonly found in rural areas?”

First,

the characters’ distinctive hairstyles reference the shape and texture of

Western orchids. Like flowers that have been selectively bred to suit consumer

demands, this allegorically expresses the human form as it might change under

the Fourth Industrial Revolution and climate change. Plants, typically

perceived as fragile beings, now symbolize the current state of affairs where

the term “plant-based” has quietly infiltrated our lives. In addition, the

artist reveals a bizarre sense of dread that arises when looking at

geometrically cultivated land through agriculture, and flowers and fruits that

have been bred to be more beautiful and delicious.

Jongwan

Jang, Go West, 2023, 227.3×181.8cm © FOUNDRY SEOUL

Jongwan

Jang, Go West, 2023, 227.3×181.8cm © FOUNDRY SEOUL

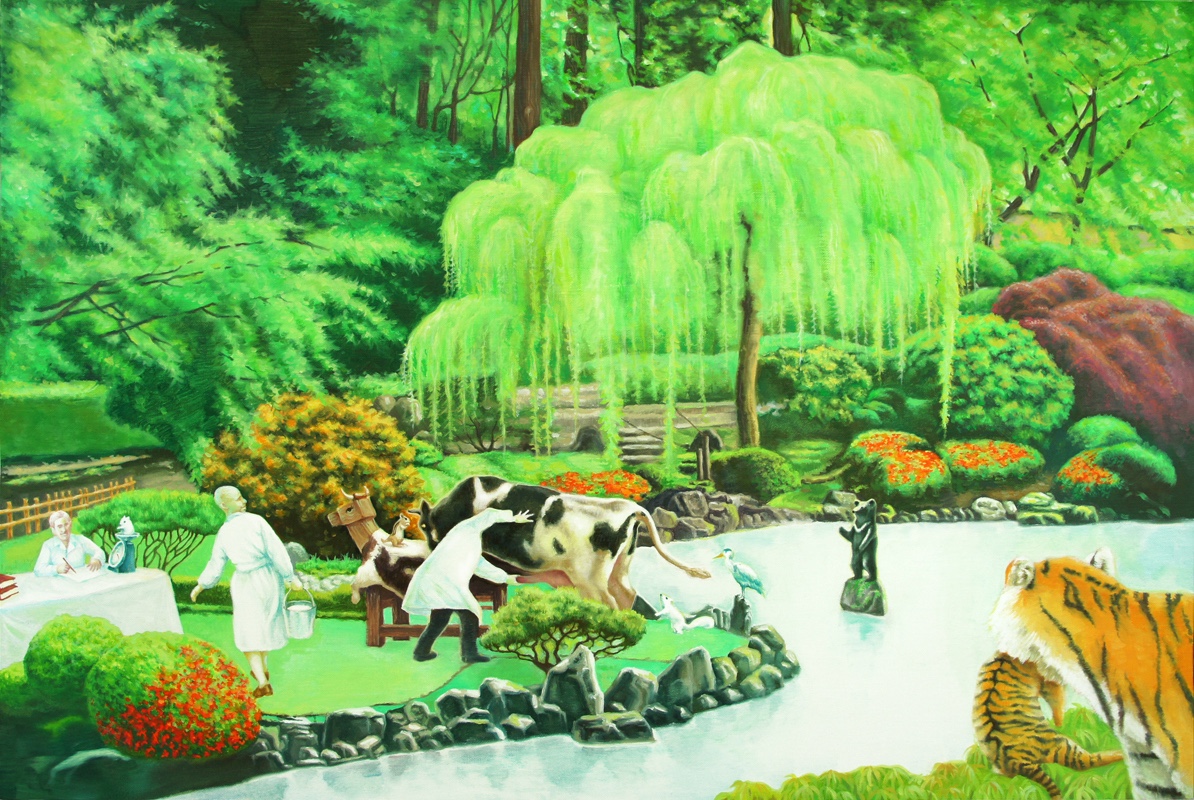

The

overall green tone of the work is also intriguing. Like the aforementioned

hairstyles, plants, and agriculture, green has ambivalent qualities. Wassily

Kandinsky once criticized green, saying “It can become tiresome after it

soothes the soul,” and Piet Mondrian said “The disorderliness of nature is

unpleasant.” Though green is often seen as a symbol of healing and comfort,

here it creates an eerie mood—no wonder Jang’s world feels strange. Yet the

artist doesn’t lay these messages bare on the surface.

Instead, he composes

peculiarly crafted images that provoke curiosity. They may seem tranquil at

first glance, but upon closer inspection, they are far from ideal. Therefore,

viewers visiting Foundry Seoul to engage with Jang’s work should not be lulled

by the “Goldilocks zone” (an environment that is neither too much nor too

little), but instead consider the discomfort that lurks behind the beauty—in

other words, the bare face of the underside.