Apollo, the god of the sun—also

the god of medicine, archery, music, and poetry, and above all, the god of

prophecy known for delivering the most brilliant oracles. The famed prophecy of

Oedipus's tragic fate, too, came from the Oracle of Delphi, the sanctuary of

Apollo. He moved the sun across the sky to bestow a rhythm of order upon the

world, and humans came to perceive time as a tangible concept based on that

celestial rhythm. Even in an age where we no longer rely on oracles, Apollo’s

name resurfaces incessantly—from America’s lunar mission to the cheap

glucose-laden Korean snack colored with artificial dyes.

The Apollo Project, launched in

1961, succeeded in landing on the moon with Apollo 11 in the summer of 1969.

Coincidentally, the nostalgic Korean snack “Apollo” was also launched that same

year, borrowing its name from the space mission. Although these were events

that took place a generation before the two artists featured in the exhibition 《APOLLO》, they are deeply familiar with them.

Because time always finds a way to return—through history, memory, retro,

nostalgia, or trauma. Through countless other methods, at times embedded in

objects, and often mediated by the format of art.

Though these methods vary, the

past is never recalled in uniformity. Memory always holds more oblivion than

recollection. Even if we believe we have stored it in objects, the result is

the same. The objects that stir memories of the past vibrate between memory and

oblivion, nostalgia and trauma, and event and repetition. The repetition that

arises from this cannot merely reproduce what came before. Repetition

generates. In the works of these two artists, repetition either collapses

objects or forces them to rupture. The divergent desires—to flatten the

three-dimensional into planar forms, or to explode the flat into

multiplicity—interfere and distort one another.

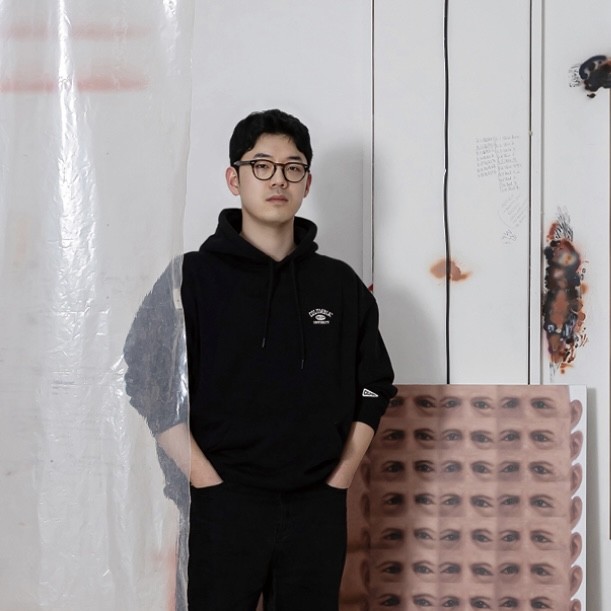

Shin Jong Min reconstructs

three-dimensional objects into flat planes. His methodology, reminiscent of

classic low-polygon modeling, invites viewers to reconsider the very

distinction between two-dimensional and three-dimensional forms. His work

blends the grand narratives of sculptural history and computer graphics with

trivial, personal, and even inaccurate memories. Especially in this exhibition,

objects such as vintage cars and rest stop snacks are used to summon the past

in a particular way. The issue is that they return in a degraded state—torn

apart, hollowed out, pierced with holes, laid bare with empty insides. In these

deteriorated forms, mediated through erosion and collapse, they are placed

before us as entirely different entities from the past. Within this

transformation, we do not face the past as it was, but rather come to imagine

the multilayered conditions that mediate it.

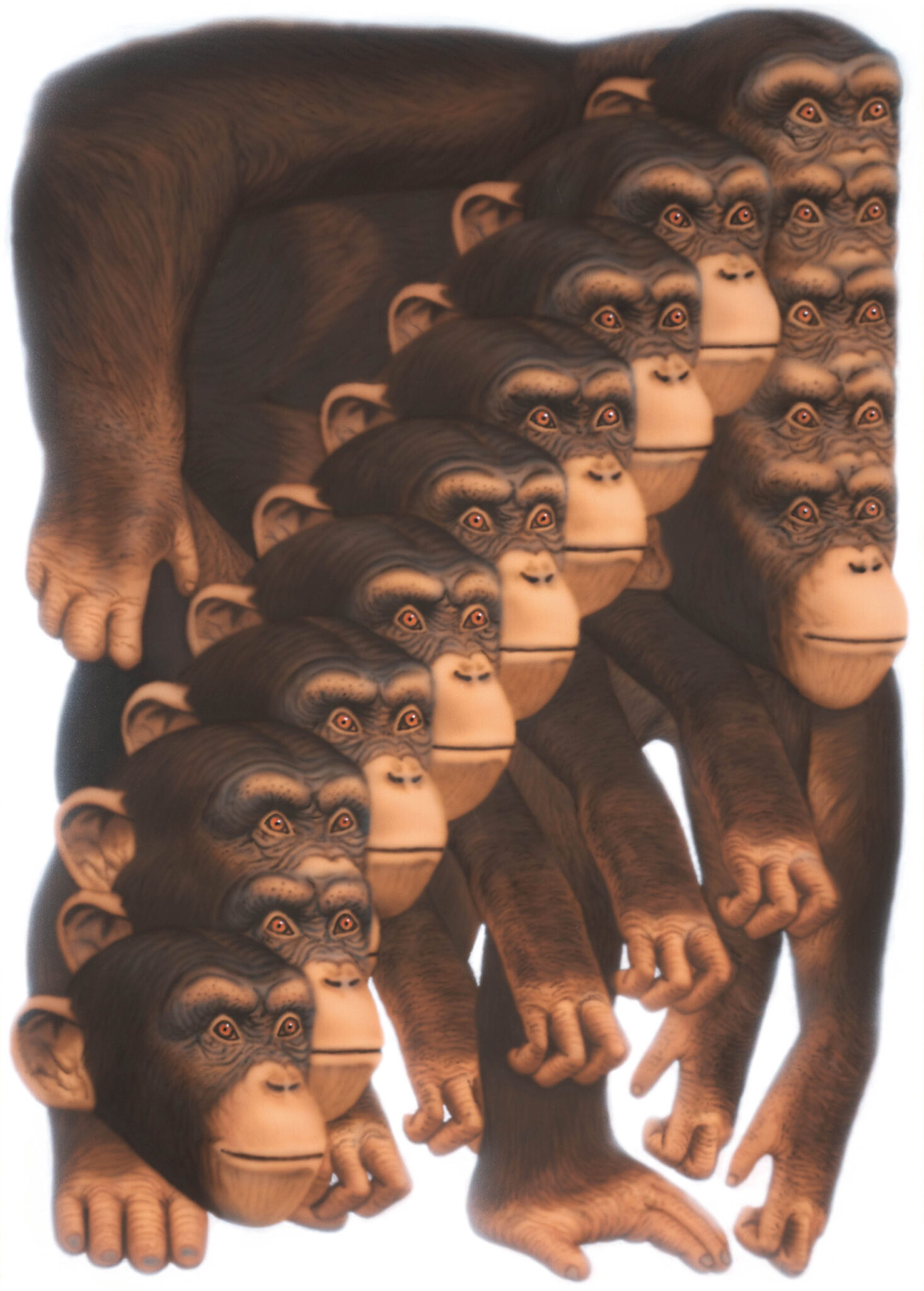

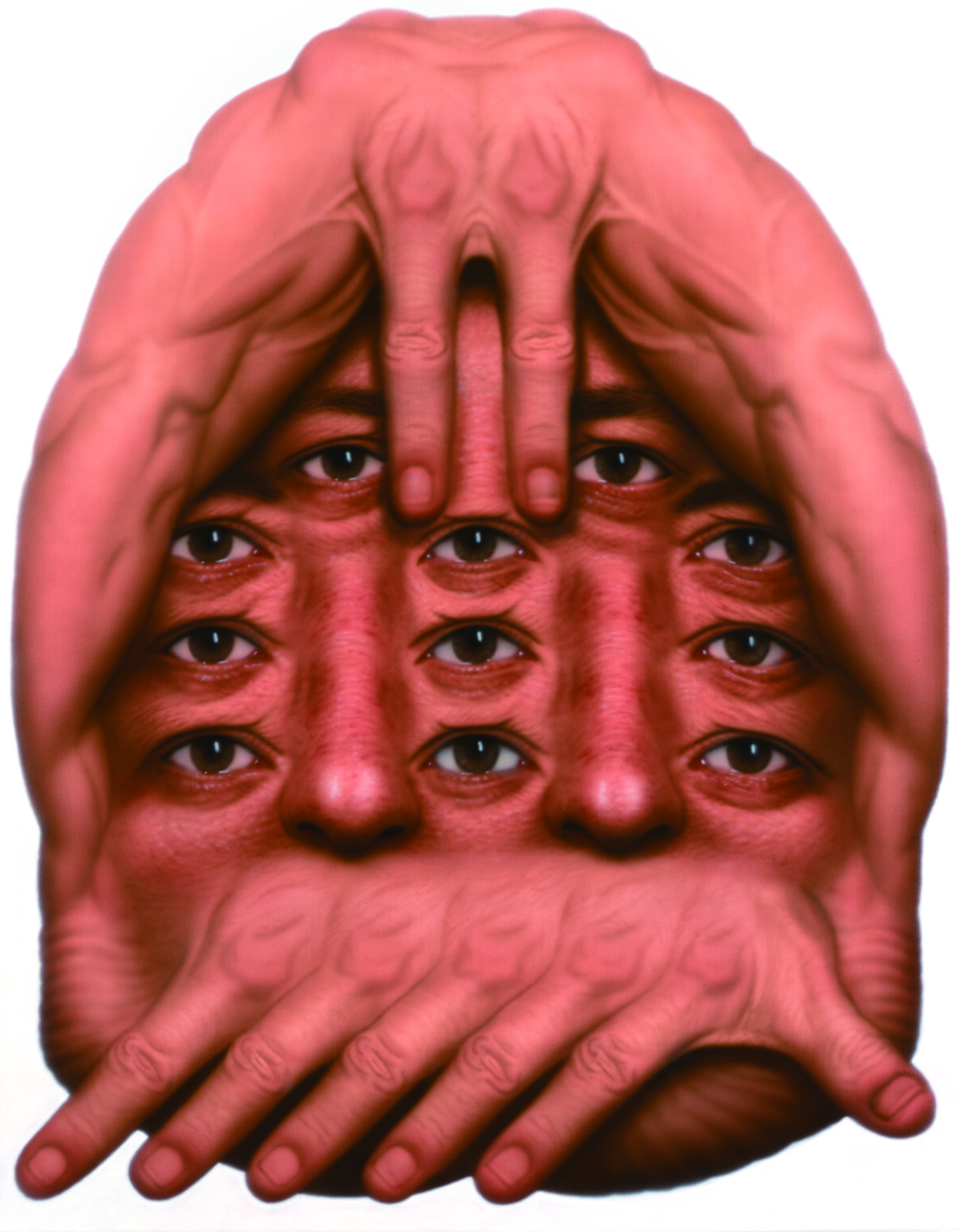

In Young Uk Yi’s work, a single

object is fractured and multiplied. Through rupture, expansion, and repetition,

the object seems on the verge of disintegration, yet interestingly, his

compositions always retain a formal sense of order. These subjects, both

multiple and singular in their organic combinations, contain chaos and order

simultaneously. When viewing his lengthy, disjunctive titles and images

together, one can often sense an intimate narrative. These narratives largely

stem from personal memories, but at times, an art historical reference—such as

Dürer’s hare—unexpectedly surfaces. The past, under various names such as

memory, nostalgia, trauma, or history, is invoked through both the personal and

the public, the singular and the plural. The rabbit, as a symbol, is both a

historical reference and a contemporary subject; it is Dürer’s rabbit, yet also

Yi’s rabbit. The stories embedded within it become Dürer’s allegory and

simultaneously Yi’s own.

The intersection of the two

artists—one exploring geometric flatness and the other organic

expansion—generates acts and counteracts of compressive and expansive forces,

prompting viewers to imagine a dynamic interplay of power. From reflections on

the conditions of sculpture and painting to the unexpected glitches that emerge

between meticulously planned arrangements and accidental deviations, the

exhibition conjures moments where Apollonian order collides with Dionysian

chaos, revealing what lies in between. It is only through order that we can

truly sense what escapes it, and only through form that we become aware of what

exists beyond it.

Like a biker gang’s motorcycle

constructed from dismembered human limbs, or a full-sized car assembled from

jagged geometric planes. Eyes that are not meant for seeing, mouths that are

not meant for eating or speaking—these elements move between bodies without

organs and organs without bodies. Between a sober Apollo and an intoxicated

Dionysus. Between familiarity and estrangement. What we witness in 《APOLLO》 may be the paradoxical past revealed

through prophecies of the future, the rupture caused by rules, the glitches

triggered in attempts to operate something, the failure that performed success,

the spacecraft and the junk food, and the inevitable overlapping of Apollo and

Dionysus.