Rendering

the Body Strange 1: Truncation

“After

mixing together panels of different sizes to determine the overall form, I made

images where the body was crumpled inside it… This part is quite fascinating.

It’s a kind of panel, and I don’t know what sort of image will be inside it,

but as the brushstrokes pass very briskly and come together within the shape,

it gives off a completely different impression.”1

Questions

of the part and the whole are important in the paintings of Chang Kon Lim. In

dealing with the human body, Lim fragments and rearranges it. Sometimes the

body’s image itself is truncated, but fundamentally the artist also emphasizes

particular elements, altering the orientation of the canvas so that the overall

bodily shape becomes difficult to recognize. The relationships among the

canvases with fragmented bodies can be disorienting, and the artist himself has

explained, the misalignments arise in the temporal and spatial context of his

image as the directions of the brushstrokes change. From the viewer’s

standpoint, it gives an impression that the same part of the body appears to

have been depicted over time.

Also,

since his subject is the human body, questions inevitably emerge regarding its

identity Often, nudes and portraits of human subjects are seen as a genre in

which the person’s outward aspects are a means of accessing their interiority.

To be sure, the purpose of the genre may differ according to the artist’s

intent—but from the viewer’s perspective, at least, we imagine what is

happening internally through our observation of subject’s forms. When the body

is arranged in a discontinuous way, it appears difficult to access the person’s

internal identity by way of their external physical form. In this respect, we

may conclude that the artist is outright denying or rejecting the very concept

of a consistent identity. Lim has also spoken of the fascination evoked by the

random combinations that arise through the mixing of parts of the body painted with

different brushstrokes.2 We may suggest that his interest lies in the

fragmented self-image that emerges when the same person’s body may seem to

represent the bodies of different individuals.

Thus,

apart from whether the artist is distorting his subject or representing it

realistically, we can say that the artist’s desire is to change the viewer’s

attitude toward the nude rather than to depict something. For the viewer, it

may be unsettling to see this truncation and focus on the surfaces of the human

body. This is the subject that the viewer most likely identifies with. But when

the artist insists on chopping the body down and rearranging it, the viewer

naturally comes to focus on the body itself. Unable to recognize which part of

the body a particular portion of flesh belongs to, they end up viewing the

human body in terms of the flesh itself and the musculature attached to its

surface.

So

how and why did Chang Kon Lim come to focus on the subject’s body as a kind of

object—like a thing? The artist has described the body as possessing an

emotional aspect: “Some bodies show themselves off, yet there are also clearly

very sorrowful emotions to them, and those things become an aggregate in such a

way that as the perspectives go back and forth within space, the viewers may

have wanted to go inside of that a bit.”3 Typically in a genre of portrait, an

artist guides the viewer to infer the subject’s emotional state through the

body’s movements or the eyes. In contrast, Chang Kon Lim’s bodies appear

functional. So why does Lim maintain that he is communicating emotions by means

of the body’s fragments and surfaces?

Rendering

the Body Strange 2: Cramming

“I

generally find it quite interesting when you have the desire to show the body

in some way mixing together with aspects that are closer to abstraction.”4

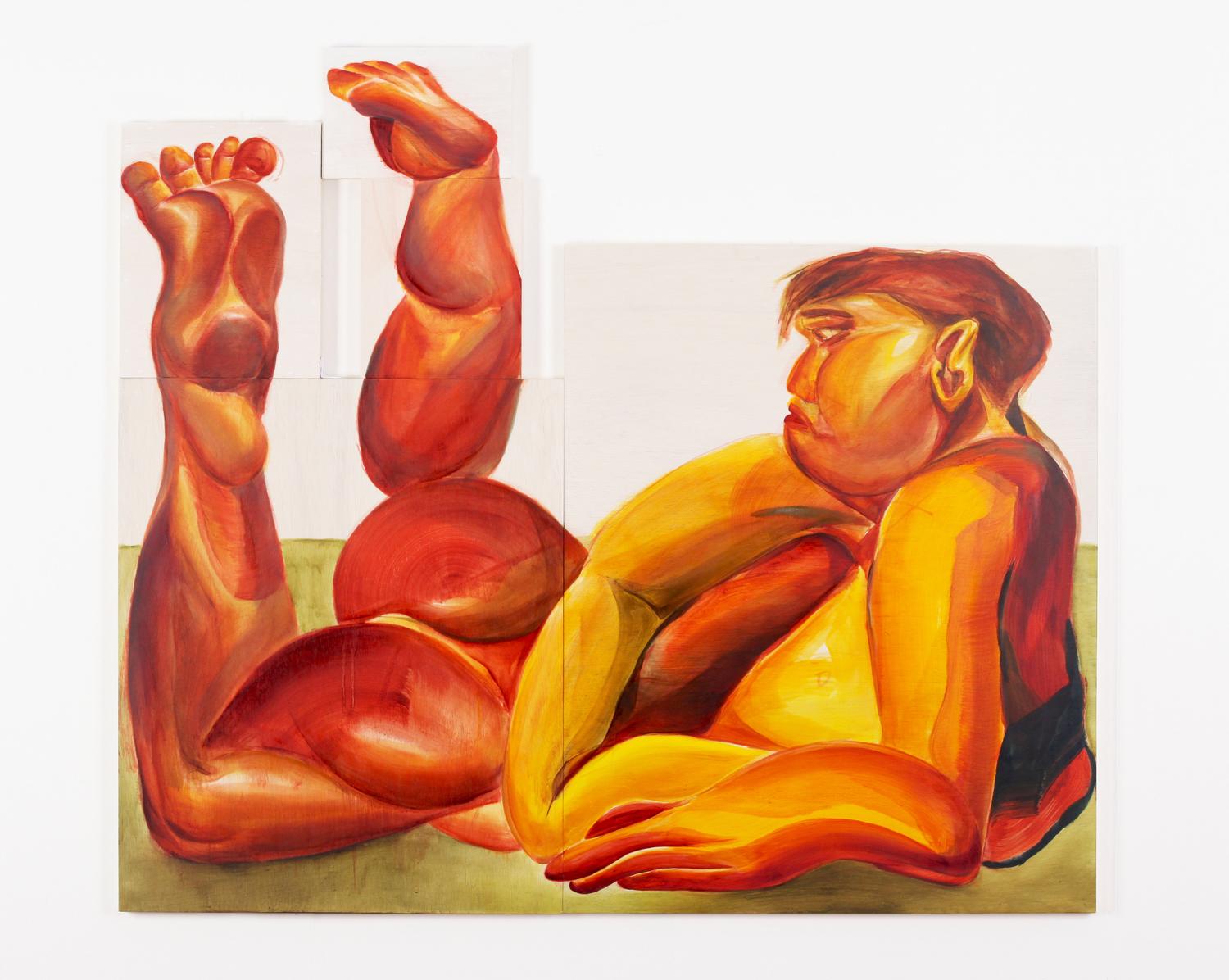

Morphing

Gesture (2022) shows a truncated body. Some parts of it evoke

associations with genitalia, others particular muscles. But because the

positions of the parts are unclear, it is difficult to identify exactly what

area of the body is shown in his panel. I describe that Lim has concentrated on

flesh and the body’s surface whereas he refers to his own process as

“crumpling” the body. In the first place, a crucial difference exists between

cutting the body apart and separating it on one hand and positioning it as if

crammed into a particular space on the other.

The

Impressionists whose work signaled the start of European modernism in the 20th

century shifted gradually away from containing the body in images, moving

instead toward eradicating the sense of spatial distance between background and

depicted object. Where an example like Pablo Picasso’s work Girl with

a Mandolin (1910) has a composition that securely sets the female

body apart within the canvas and forms the subject with lines that suggest its

different parts, his famous Portrait of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (also 1910)

presents the background in coarse brushstrokes. The former is abstract painting

by fragmenting the human body, whereas the latter is “a materialization of

background space.”5 Moreover, the latter approach tears down the practical and

conceptual wall between represented object and background. Ultimately, Picasso

can be said to have achieved flatness by merging the background and the

foreground object rather than adopting the traditional method of portraying a

subject on the canvas and filling in the space around it.

Interestingly, Lim’s nudes also reinforce

the body’s materiality through their coarse brushstrokes. Where the paintings

from Picasso’s Analytical Cubism period seek to eliminate the distance between

foreground and background, Lim’s paintings also fill the canvas with the body

until there is no empty space left. The result is that there is no real

background left to speak of. The methods and aims may be different, but Lim is

also emphasizing materiality and immediacy, and the panels themselves are

entirely filled in their arrangement and dimensions. He approaches his subject

with the sense of a sculptor, pervading nearly the entire surface, rather than

adopting an approach of virtual space or the placement of an image upon his

canvas.

Explaining

his method of cramming the body into space, Lim has said: “I think I wanted to

image something more or less projecting out of space rather than being simply

contained by something like a wall or floor. So for example, you might have a

space like this when it kind of pushes out to disrupt the viewer’s movements.”6

While Lim is a painter, he may be said to approach his work like a sculptor or

installation artist, stuffing the body inside the space of a canvas.

In

the process of approaching the human body in an objective way, Picasso also

muted and transformed the tones of his colors as much as possible. Tones are

likewise limited in Lim’s case. By presenting skin predominantly in brick tones

and shades of red or reddish-brown rather than lighter flesh tones, he makes

the skin appear unfamiliar. Just as the Cubists limited their palette to show

their subject fully as a pictorial experience rather than an object of

emotional identification, Chang Kon Lim represents his subjects powerfully in a

few limited colors, in much the same way that mountains might appear in a

landscape image.

Ironically,

the amplified size and weight of the body reflect the paramount importance of

the body as a theme in Lim’s body of work. In the work shown at his Gaze

(2020) exhibition, the crumpling of body images into corners renders the body

extremely strange, while also potentially heightening the viewer’s attention to

particular parts of it. It is a sort of two-sided technique that focuses

attention on something by rendering it unrecognizable. In this regard, Lim has

explained this focus was on the curious phenomenon where an abstracted body

nevertheless appears specific due to powerful surface effects. By separating

the parts of the body —the buttocks, the arms and legs—and arranging the

divided canvases in different directions, he presents them looking unfamiliar,

causing the viewer to step away from their conventions, functions, roles, and

external similarities to focus from an entirely different perspective.

Rendering

the Body Strange 3: Heightening Curiosity

“What

I wanted to do was to bring all these figures together into a kind of

landscape. So you have things like gay people recognizing each other but

pretending not to, you have some bodies that are really showing off, yet there

are also very sorrowful emotions that are clearly there, and all those things

are assembled together. …”7

In

simple terms, Chang Kon Lim problematizes ways in which society approaches the

body. To elaborate, he may be seen as experimenting with problematizing and

transforming the perspectives that society applies to bodies, particularly male

ones. There is nothing sedate about the surfaces of these male bodies, which

appear both objective and powerfully rendered, with red veins showing through.

They are not beautiful. Yet when the body is rendered strange, it may become an

object of curiosity and powerful voyeuristic fascination. Additionally, we see

the example of The Open Path (2023), where the central part

where the body should be has been cut out.

In

this sense, the artist may be seen as conscious of the perspective that the

viewer typically has applied to the male body or nude as an erotic object. In

an example like Shelter with Egg (2023), he magnifies what

is either a genital shape or a joint resembling one. Viewing canvases where

genitals and other body parts are mixed together or otherwise confusing and

interchangeable, we start to think about our own preconceptions about particular

parts of the body. The image of them seemingly being trapped in boxes may also

be seen as alluding indirectly to a situation where sexual desires relating to

the male body are marginalized and treated as socially taboo. Surfaces that

show what appears to be muscle or flowing blood may alternatively be viewed as

allegories for sexual excitement.

Traditionally,

the peephole is an instance where sexual curiosity is intensified through the

dual aspects of concealment and exposure. One representative example of a film

relating to voyeurism directed at male subjects is Andy Warhol’s Blow

Job (1964), in which the male figure’s lower body is never shown, and

the viewer must continue observing his face. For the viewer, this is a

tightrope walk between the visible, the seen, and the unseen. Imagining the

unseen or unseeable leads in turn to erotic curiosity toward the subject.8 The

duality in Chang Kon Lim’s painting falls along the same lines. Observing his

hyperrealism, we may view the male nudes as being ostentatious, but in a

stricter sense, they are for the most part fragmented.

Partially revealed

genitals and joints may arouse erotic curiosity, but as the artist himself has

observed, the curiosity is amplified when unidentifiable abstraction is mixed

with the recognizable.

In

this sense, the surfaces of these objective male nudes perform two roles. In

Lim’s paintings, bodies appear strange. Paradoxically, the hyperrealistic

techniques contribute to rendering the subjects less familiar-seeming. As in

all defamiliarization strategies, the viewer’s curiosity is engaged when

something is made unrecognizable.

A

new lineage of synesthetic male nudes

As

I mentioned in the introduction, Lim has attempted to evoke emotional

reverberations with his nude images. So how does the male body elicit emotional

reverberations when it is approached in such an objective way? The partially

revealed genital images evoke homoerotic themes that are uncommon in Korean

painting. The artist makes no secret of this theme, yet he does not employ

specifically gay codes either. He continues to paint male nudes, but his

artistic aim is less a matter of sensationalism than one of encouraging the

viewer to re-examine and re-experience their own desires and preconceptions

toward the naked body.

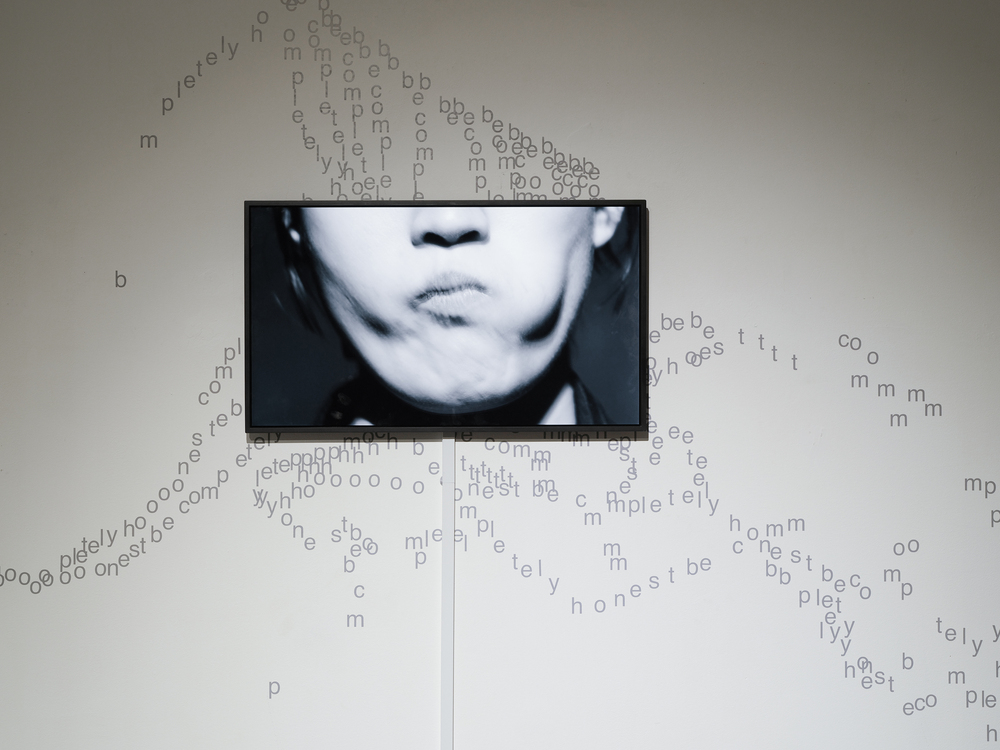

The

objective body surfaces signify a shift from vision to other senses. To begin

with, the visually roving eye naturally comes to focus on the body’s surface.

In a renowned writing during the 1970s, Laura Mulvey described how the female’s

body has been reduced to and exploited as a sexual object. In Chang Kon Lim’s

painting, it is male rather than female nudes that are otherized. Moreover,

they are turned into odd objects that the viewer wants to look at and feel but

cannot touch. Touch is a sense that leaves reverberations as powerful as those

associated with vision. Synesthetic stimuli have the effect of augmenting our

imagination of other senses such as smell.

In

this, Lim’s works shift from paintings seen with the eyes to paintings seen

with the body. Indeed, the diversity in his compositions and enriched and

irregular surface effects can be understood in this context. In Flowing

Light (2023), the artist has explained that he wanted to depict the

inside of the body. Because of his use of a shaped canvas, the texture of the

trimmed wood panel is conveyed fully. His actions here enable a multifaceted

perception of the viewer’s gaze and the role of the body—a role that

diversifies from an object of contemplation to one that can be touched or seen

into.

In

a broader sense, this more diverse role for the body—specifically the nude male

body, on display in the public realm—means that the male nude is no longer

being concealed. This signifies a shift in the male nude from an object of

erotic contemplation to something that can be touched. At the symbolic level,

visual contemplation has often been associated with the concept of

infiltration; in the same context, the male nude is now exposed to infiltration

from outside.

To

be sure, the new revival in performances and conceptual art in the Korea of the

1980s and 1990s brought instances when males exposed their own macho bodies.

For them, self-exposure was predominantly a means of forcefully expressing

themselves in a gesture of resistance against social repression and taboos. In Chang

Kon Lim’s paintings, the naked male body exists uncomfortably within a defined

frame. It is crammed in space, partially deconstructed and truncated. At the

same time, his painted male nudes are somewhat removed from the male nudes that

have typically been represented in allusive ways relating to homoerotic codes.

Even when they are wedged into tight spaces, these male nudes are represented

directly and realistically rather than allusively. From this standpoint, Chang

Kon Lim’s nudes carry on an uncommon lineage of the genre within Korean art. As

images that encourage reconsideration of the aesthetic and visual meaning of

the nude male body instead of its homoerotic associations, they carry on an

important lineage in the medium of nude painting.

1

Interview with the artist Chang Kon Lim, interviewed by Dong-Yeon Koh, Seoul,

June 6, 2024.

2

Ibid.

3

Ibid.

4

Ibid.

5

Rosalind Krauss, “Flattening Space,” London Review of Books, vol. 26, no. 7

(April 1, 2004): 30.

6

“To me, the difference between parts with and without a body seemed like

discrimination, so even if they thought I should make them separate, I worked

with a kind of crystallization where I would cut them apart like this and they

would put them back together.” Interview with the artist Chang Kon Lim,

interviewed by Dong-Yeon Koh, Seoul, June 6, 2024.

7

Ibid.

8

David Lancaster, “Andy Warhol’s Blow Job,” Film & History: An

Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies, vol. 34, no. 1

(2004): 92