In

this exhibition, the artist focuses on the units of time, selecting fragmentary

memories of scattered time, and sensing the smallest particles of recollection.

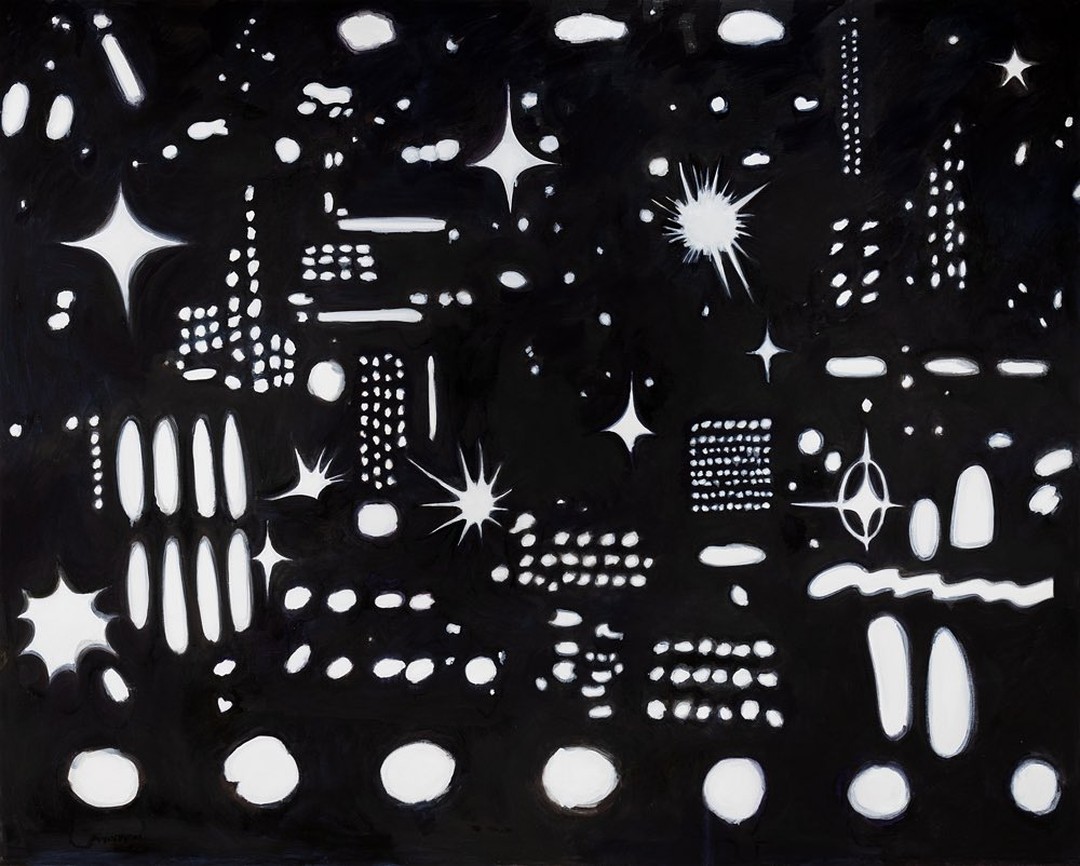

The key works of the exhibition, the black-and-white paintings Looking

at the Universe (2021) and From a Grain of Sand (2021),

are presented as a pair, reflecting the artist’s approach to viewing objects as

particles of time through the scale of the canvases and the titles

themselves.

From a Grain of Sand, inspired by the first

line of William Blake’s Auguries of Innocence (1863)—“To see a World

in a Grain of Sand”—serves as a metaphor for the accumulation of time within a

single grain of sand, as the artist projects herself into seemingly trivial,

ordinary moments. The two works, which intertwine the nighttime setting with

landscapes and portraits rendered in black-and-white, are relatively restrained

and concise, with their subjects loosely zoomed in.

In Looking

at the Universe, originating from small pencil sketches, the forms of

light spreading across the nightscape differ from Jeong’s previous landscape

paintings by emphasizing the intense sensory contrast of immaterial

forms—darkness and light. Unlike her earlier works, which documented landscapes

realistically, the elements that once depicted the scene are eliminated,

leaving only shadows and light. The dark tones of indigo, sepia, and Payne’s

gray—applied thinly across the canvas surface—create silhouettes of scenes as

the landscape expands and becomes abstract. The juxtaposition of rough

brushstrokes and blended colors constructs nightscapes and portraits with

enigmatic expressions, amplifying tension and inviting viewers to imagine what

lies beneath through the enlarged, close-up compositions.

The

figures in Yiji Jeong’s paintings seem to reside there, indifferent yet

present. Each moment the artist chooses how much of the time spent with the

figure and the surrounding space to depict on the canvas. Sometimes the focus

rests on the figure itself; at other times, the viewer’s gaze expands to the

unique structure and atmosphere of the place, as in works like Bass

Lesson (2021). Accordingly, Jeong internalizes her subjects,

leaving their interpretations open to viewers or emphasizing the work’s

character as a personal record, restructuring each piece with subtle

differences in direction.

Such

concerns about how subjects and environments are framed on canvas permeate

Jeong’s overall practice. As observers, we tend to focus on her use of color

and subject matter, yet what matters more is her treatment of each scene as a

distinct “cut,” akin to a frame in comics. If we consider the canvas as one of

many sequential frames connecting the story, we can infer that the artist’s

storytelling method and freedom play a significant role in her painterly

language. Drawing from comic techniques that capture scenes within frames,

Jeong selects and presents compressed, refined moments—easily understood and

striking—amid the omissions and gaps of time.

The

fragmented delivery of these “cuts” within disassembled time encapsulates

transient states of existence, memory, and anticipated futures. Fascinated by

this quality, Jeong steers her painting practice toward a mode of

documentation. Much like the literary “cut-up” technique, where fragments of

text are rearranged to form new compositions, Jeong translates images of memory

into painting without rigid boundaries. Unlike the safe, defined borders

surrounding cartoon frames, the artist removes outlines, leaving the canvas

exposed so that viewers may freely imagine the emotions and sensations of those

moments before and after what is shown.

In

seeking ways to convey the emotions that certain moments evoked in her, Jeong

adopts the unapologetic, amateurish methods of raw comics. Rather than

mastering perfectly polished comic grammar, she chooses the cut-based approach

available to the inexperienced. Consequently, figures in her paintings are

emphasized with bold outlines, while backgrounds such as landscapes and still

lifes—seen in works like Poetry Book and Taxi, Your

Name, Greeting with Eyes, and Terrace (2021)—are

rendered more realistically with tonal shading, lacking outlines. This

comic-like discrepancy paradoxically draws viewers deeper into the figures

themselves, filling the composition with a contradictory sense of immersion.

In

Yiji Jeong’s paintings, bold cuts recall personal memories and experiences,

while simultaneously determining the viewer’s position beyond the frame. The

trivial yet enduring moments we remember often linger with the density of the

air, the scent of someone nearby, the weather, objects in the space, the

surrounding landscape, and the people who were present. Thus, contemplating

these fleeting instances becomes a means of recording the most peaceful moments

amidst the bittersweet whirlwind of youth—its regrets, preciousness, futility,

and longing.

Though

her hollow feelings may seem to conclude neatly within a single frame, the

artist leaves lingering gaps to imagine the next line between frames, soothing

an unfilled sense of emptiness. The fleeting moments in life where one

confronts oneself amid repetitive daily routines are easily lost. To grasp

these vanishing sensations, Jeong assembles her memories like the varied stones

of a wish tower in The Shape of a Wish (2021),

loosely yet earnestly leaving behind echoes of her expectations and determination

for the next chapter.