Solo Exhibitions (Brief)

Nosik

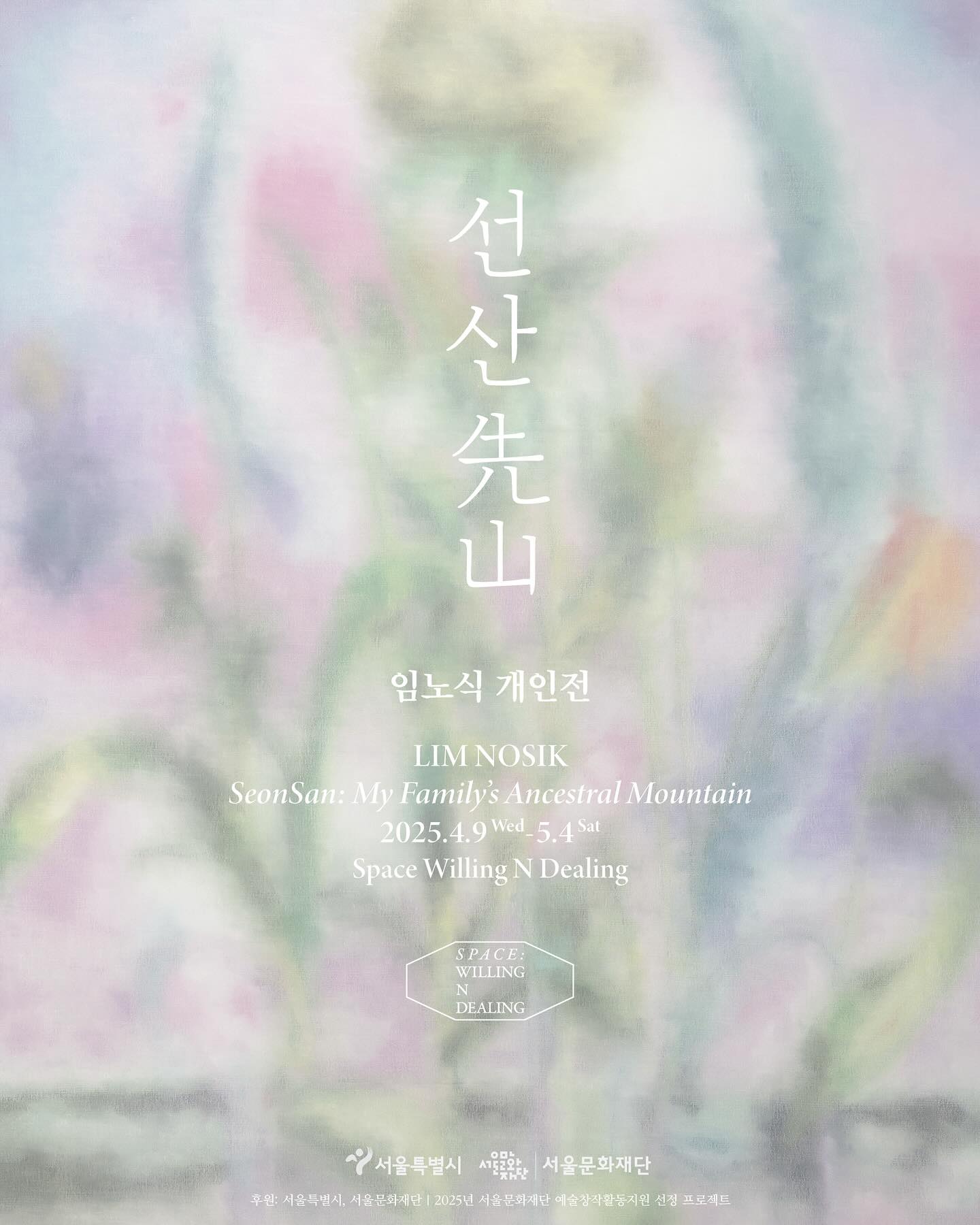

Lim was represented by solo exhibitions including 《Seonsan: My

Familys Ancestral Mountain》 (Space Willing N Dealing,

Seoul, 2025), 《Where Shadow Linger》 (Space Æfter, Seoul, 2024), 《Deep Line》

(Kumho Museum of Art, Seoul, 2023), 《Unfolded》

(Project Space Sarubia, Seoul, 2023), 《Pebble Skipping》 (Artspace Boan 2, Seoul,

2020), and 《Folded Time》 (Hapjungjigu,

Seoul, 2017).

Group Exhibitions (Brief)

Lim

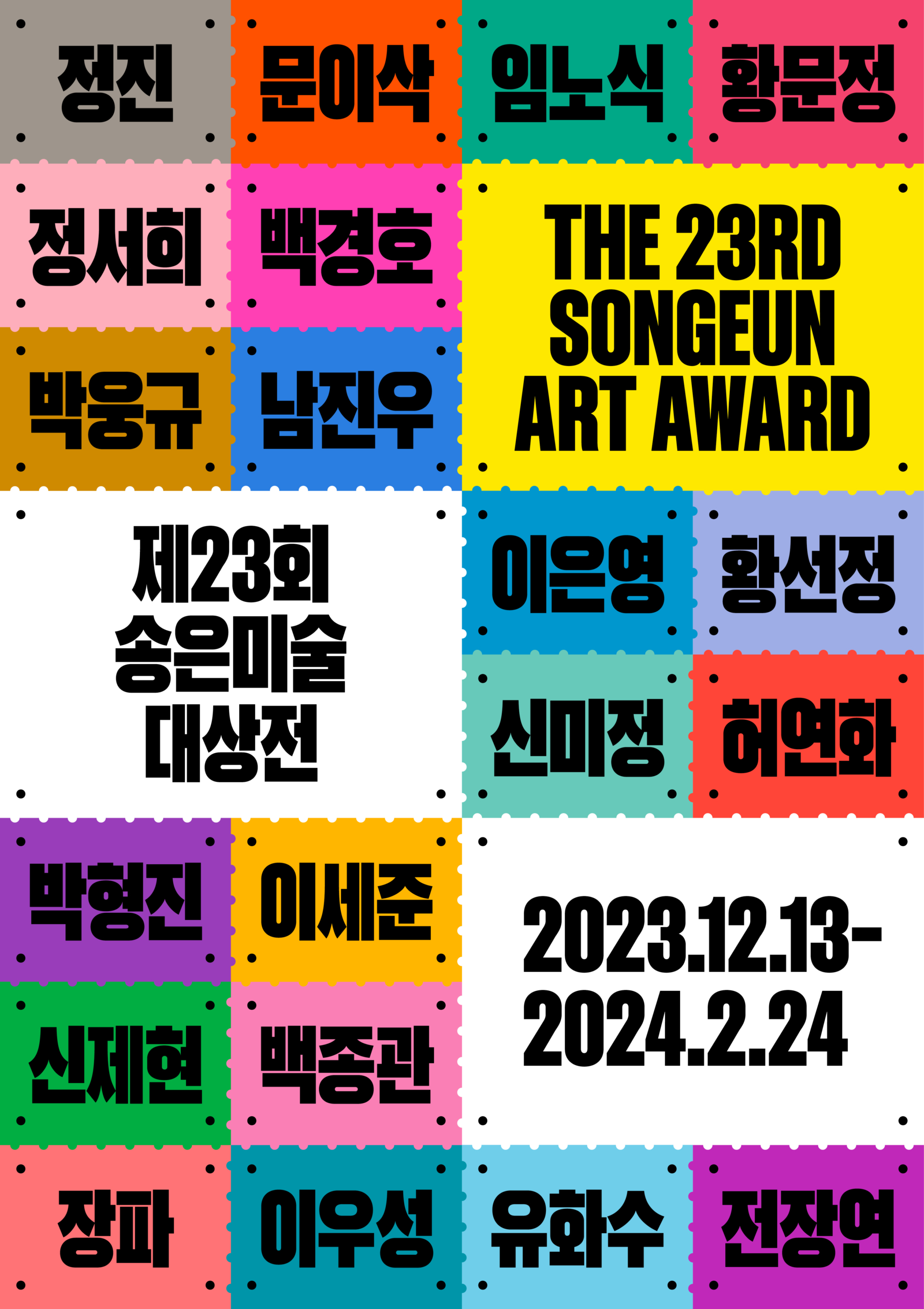

has also participated in numerous group exhibitions held at Arario Gallery

Shanghai (Shangai, China, 2025), Arario Gallery Seoul (Seoul, 2024), SONGEUN

(Seoul, 2023), Ilmin Museum of Art (Seoul, 2023), Art Center White Block (Paju,

Korea, 2022), SFAC Seoul Art Space Geumcheon (Seoul, 2021), Amado Art Space

(Seoul, 2020), and more

Awards (Selected)

He

gained attention for being selected in the Kumho Museum of Art and Kumho Young

Artist 2022.

Residencies (Selected)

He was the artist-in-residence at the SeMA

Nanji Residency in 2019, Incheon Art Platform in 2020, and the SFAC Seoul Art

Space Geumcheon in 2021.

Collections (Selected)

His

works are collected by institutions such as the Seoul Museum of Art, Gyeonggi

Museum of Modern Art, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art’s Art

Bank, Ilmin Museum of Art, ARARIO MUSEUM and more.