Kim

Shinrok × Son Hyunseon’s Absent Time ultimately

pursues the medium of theater. This is possible because Kim Shinrok accepts Son

Hyunseon’s work as a task, and as a result, the work is incorporated into the

present as a backdrop or object that organically connects with existence. How Son

Hyunseon’s works, which ‘cast themselves’ upon the stage, are treated, and how

they are included within the world of the play, determines whether they

function as pure backgrounds or as imperfect points of departure. The fact that

they emerge somewhat awkwardly, rather than seamlessly, reveals not the

impossibility of collaboration but certainly the difficulties inherent in it.

The

text regarding Transparent-Body (gel medium on

transparent film, 2024, dimensions variable) reads more like an abstract poem

at first, which seems intended to converge, to some degree, with the recursive

nature of the artwork itself. Standing before Transparent-Body,

Kim Shinrok’s narration refers to the ‘transparent’ integration of their own

body, and ultimately, the body that exists as a translation, explanation, or

expression of Transparent-Body concludes with the

utterance of the artwork’s caption information, as if the body is absorbed back

into Transparent-Body, acting as its proxy or

substitute. In short, it erases the distance between Transparent-Body and

the body, treating the body itself as if it were transparent.

While

this could be considered a gesture of respect and a performative homage to the

work, it also takes on a peculiar dimension. Since this is expressed through

spoken text, the final utterance of the caption, “Kim Shinrok,” should replace

the conclusion. The notion that the artwork title has read itself is based, of

course, on Kim Shinrok’s ghostly presence—on Kim Shinrok becoming a ghost. To

be precise, the correct, complete caption should begin with “Son Hyunseon,” but

this is omitted. Is it an exaggeration to view this act of caption-reading as a

safeguard for establishing an equal footing in the collaboration?

If

the incomplete caption serves as a ritual to firmly distinguish Son Hyunseon’s

work as “artwork,” then perhaps the absent names “Kim Shinrok” and “Son

Hyunseon” are excluded to avoid transgressing the boundaries of Absent

Time. Nevertheless, could this omission be the decisive clue

revealing that it is not Son Hyunseon’s work or Kim Shinrok’s theater that

constitute the artwork, but rather Son Hyunseon and Kim Shinrok themselves who

have become the artwork? Rather than the work itself, is the context

surrounding this project perhaps inclined toward the star-like presence of “Kim

Shinrok”? What matters, therefore, is evaluating Kim Shinrok’s trajectory as an

artist and creator—what path they have walked, and what significance this work

holds within that trajectory. As stated at the outset, Absent

Time extends into the stage as Kim Shinrok’s theatrical

platform, with Son Hyunseon’s work accepted as a task to be carried. Even if

Son Hyunseon’s works are decisive, it is Kim Shinrok who ultimately extends

them purely into performance.

Transparent-Body appears

once more at the end to close the play, but it is not strictly connected to the

theatrical narrative. The textual purity of Transparent-Body is

preserved. It does not seamlessly blend with the rest. What occupies the

middle—what takes up most of the duration—is the decisive text of playwright

Kim Yeonjae. Is that text itself titled Absent Time? Or

has this collaboration merely circled around a promotional model typical of

contemporary art? The play’s text is fragmented and treated as such. It

disperses throughout the space, much like Son Hyunseon’s works are dispersed

across the theater, deriving from the performers’ actions. The absence of a

stage is decisive—it reveals the “absent time” of this theater.

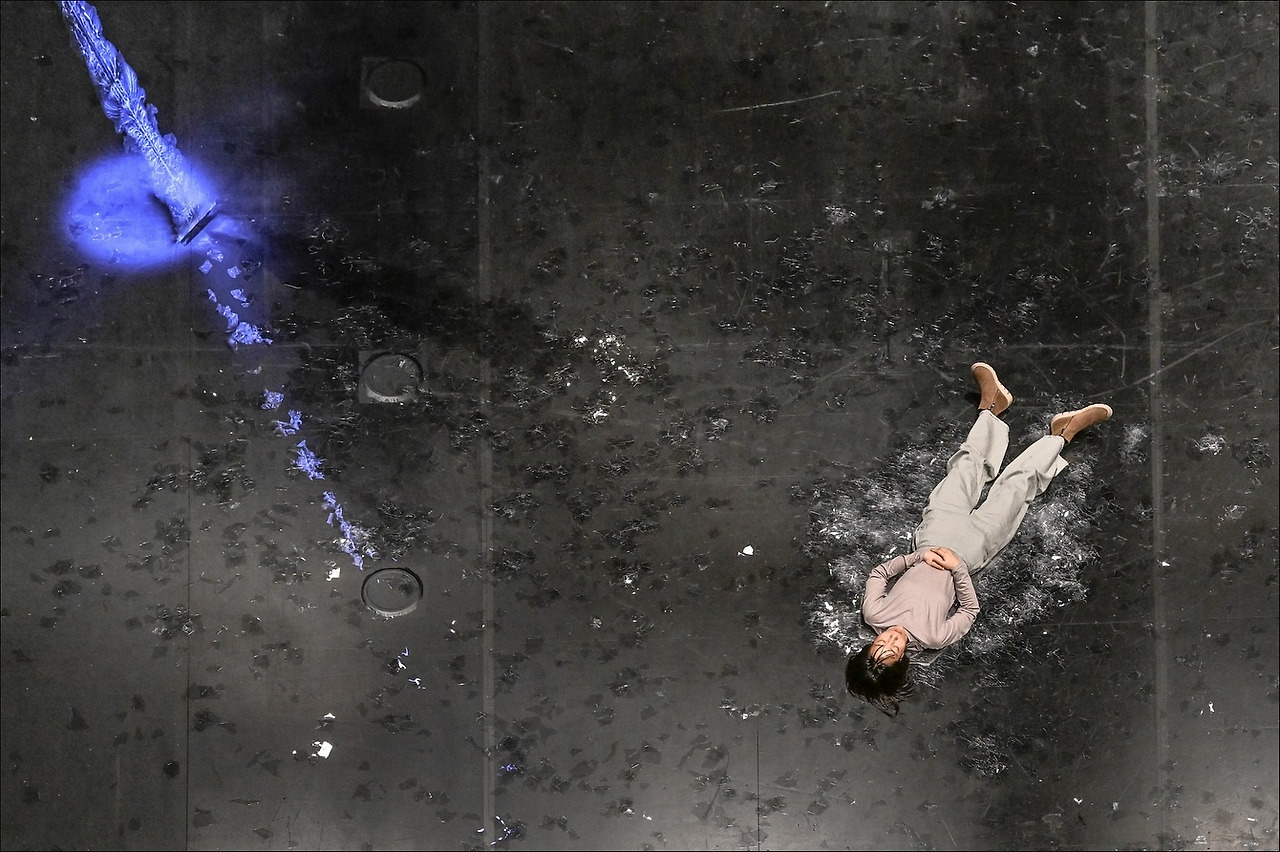

Rather than a

singular, constructed stage organizing the multilayered nature of the world,

the dispersed objects and the bodies wandering among them—filling the empty

spaces throughout the theater—become the stage. As the bodies act as

substitutes for the stage, Absent Time becomes,

true to its title, a time that erases itself, a time that witnesses its own

disappearance.

At

this point, closely handling the play's text itself does not seem particularly

crucial. Rather than purely implementing its content, the text exists as a kind

of appropriation to demonstrate how it is treated. If Son Hyunseon’s works are

the visible task, then Kim Yeonjae’s play becomes the invisible task. That task

functions as a kind of proof regarding the actor, regarding the very nature of

performance itself.

This

can be summarized into a few techniques: speech that follows a simulation where

words are thrown slowly toward a distant space, speaking methods that result

from a sharp balancing act between bodily relaxation and extension, the

concretization of speech through non-ordinary vocabulary expressed as

utterances—all these elements come into play. Though labeled under the

director’s domain, Kim Shinrok appears to occupy an ambiguous or faintly drawn

position as an expanded actor, who prioritizes testing their own performative

domain by incorporating differences in each actor's share of responsibility.

Broadly

speaking, the characters seem to share a deep layer of time, a stratum of old

memories, and as this disperses throughout the space, vague correlations of

different relationships are physically enacted. (One might wonder whether this

fragmentation originates from an inherently dispersed text, or whether it

results from intentionally fragmenting the text for spatial dispersion.) Direct

connections emerge as tightly interwoven interactions between bodies, forming a

stark contrast to the otherwise diffused relationships. These memories are

presented through leaps in time, and while actor Jo Yeonhee, who appears first,

struggles with the confusion of rapid temporal compression, those unaware of

the time shift maintain their presence in the past. Notably, the present state

of the child version of Kim Shinrok incorporates the identity of the child,

adding a unique resonance to Kim Shinrok’s otherness, which reverberates

peculiarly across all the characters.

The

rough narrative—where the wife, who suffered violence from the dog seller,

turns out to be Kim Shinrok’s friend, and upon discovering this, Kim Shinrok

kills the dog seller, who had always seduced and clung to her, and joins her

friend—is not conveyed with clarity. Fiction, by being witnessed directly in

front of one’s eyes, asserts its fictionality as the viewer’s domain—the fourth

wall is so close and distinct that it seems to replace the content altogether.

In other words, the fragments of narrative unfold less through development and

more through physical imprinting, quickly disappearing as each character's

portion of responsibility is treated and performed.