Just

a few years back, there was a revival of media installations based on machinery

theory. These works, which emphasized the technological aspects produced

through programs and coding, were very often merely superficial, with an

emphasis on their interactive aspects. I began questioning the limits of

collaborations between technology and art. Conversely, it also started to

become meaningless at some point to impose definitions of “genre” when

approaching media/video installations that were not focused on video editing

and its content as such, but applied very personal methods and techniques based

on the media “language” that broadened beyond the level of technological

concepts.

I had the opportunity to see Ahram Kwon’s Words without Words (2015)

at the 2018 Seoul Museum of Art collection exhibition The Lost

World, which finished up this year at SeMA’s Buk-Seoul branch. A

two-channel monitor was placed on the ground as though in a blackout,

flickering between the white screen in the foreground and the stone textures

with their marked black-and-white contrast. The screens changed rapidly to the

ticking beat of a metronome. The coarse mineral surfaces were quite candid and

powerful. Appearing at the same rhythm as the images of surface texture,

excerpted sentences from the text work Faust appeared with result

value errors as produced by a translation device. The data errors that emerged

in the phrases seemed somehow poetic. Like a work of anti-theater, the texts

and their incorrect phrasing deconstructed cause/effect and tense, leading to

the conclusion that the time contained within the images and language of memory

can be crude and systematized. It is like Kwon is collecting stones at random;

recalling the words of Faust – “Stop, moment, you are truly

beautiful!” – she begins to observe her memory images in an exceedingly flat

way, like minimal cross-sections.

In 2010, the artist studied in Britain and took part in residency programs in

Paris and Germany. By 2016, she was presenting metaphorical works of video and

installation that posited language, time, and the body as tools and means for

supplementing media. In her work between 2013 and 2015, the idea of “language”

was a central focus, which she regarded as a device for mediating communication

and tool for translating the vertical to the horizontal. Living in Paris and

studying abroad, she experienced a sense of alienation and frustration from

having to communicate in a foreign language rather than her own; based on this

experience, she speaks about the impossibility of perfect communication. The

ashes of words II (2013) is an ink-colored structure with a more

sculptural quality than her later work. It adopts a monumental form as a way of

underscoring a sense of irony, with the erasure of the fluidity and vibrancy

that normally underlies language.

In 2015, Kwon’s work would begin to combine the functions of language with the

properties of media, introducing symbolic elements from literature such as

short fiction works from literary contests and the poetry of Sungbok Yi. On her

monitors, she would repeatedly show structures of division, tenses, and

meetings that arose beyond her own will – part of an attempt to expand beyond

the bounds of cinematic structure and video art. While she has continued to

employ language as a medium, the accumulated layers of references have brought

her to the limits of linguistic work, amid issues concerning the ability to

communicate. She would change course from there, using “words” as a material in

themselves and adopting a formal approach involving the “flatness” of media as

a way of avoiding becoming trapped within the frame of language. For example,

she may place five channels of video on the floor and equate the monitor’s

installation structure with the human body to match the perspective of the

text. Or she may use language itself as a supplementary medium as she focuses

on surrounding objects.

What do words and time represent to Ahram Kwon? “Words” contain psychological

or physical memories, yet Kwon is constantly keeping in mind that perfect

communication is impossible to achieve, perceiving how the individual’s

peripheral narratives are not labeled according to geographic position.

Adopting a metaphorical approach to media that deconstructs the elements making

up various systems beyond the concept of space – such as the “community” and

“state” – she focuses intently on perceiving the positions and images of

objects that alternate between the real and virtual. In Drifting

Coordinates (2016), she establishes x- and y-axes and centers

the weight on an installation structure that appears on the monitor’s screen,

translating the virtual textures and temporal position of flat surfaces in

physical space into an act of “tagging.”

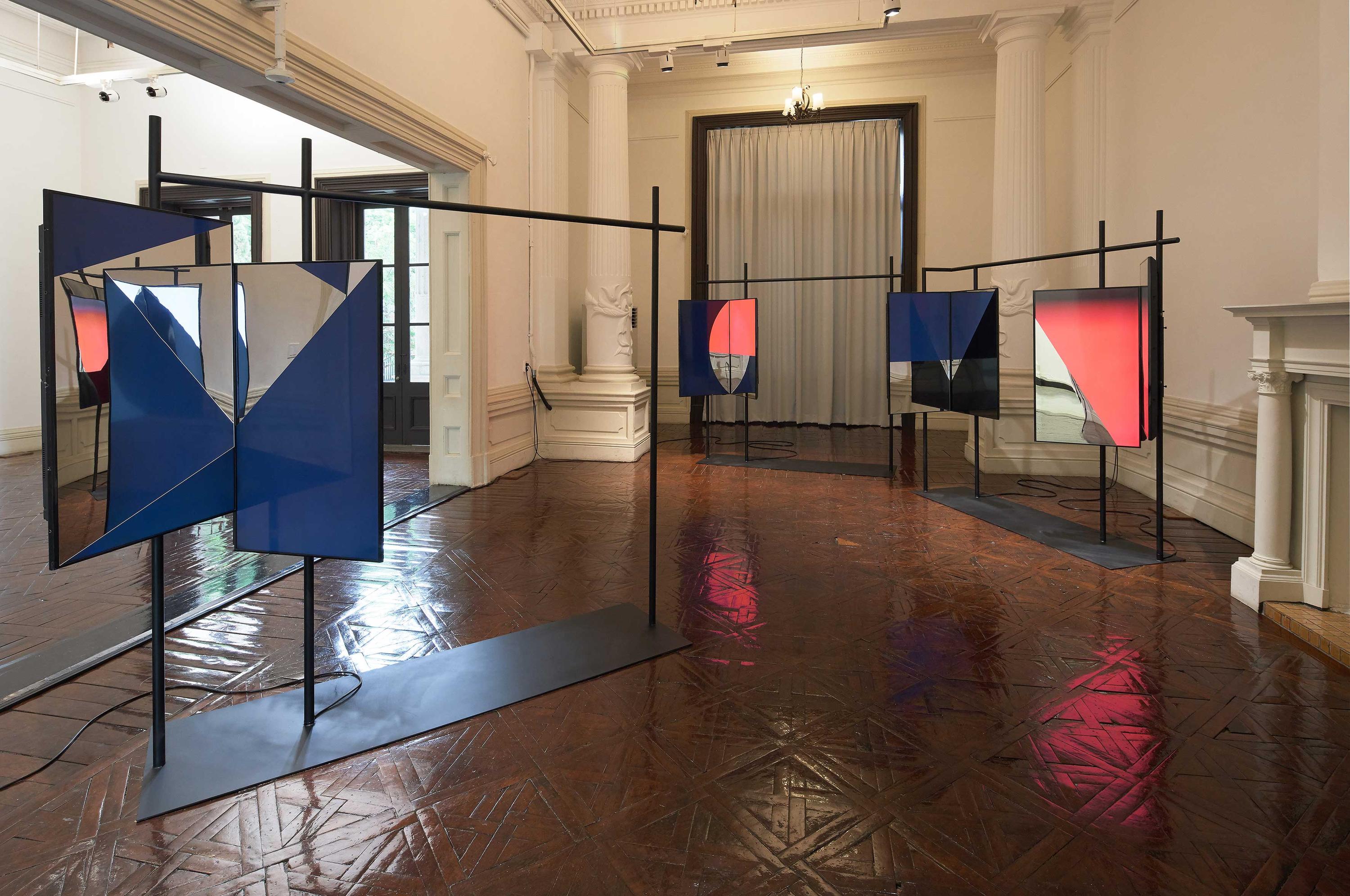

With Flat Matter (2017), the concepts through this

language and media operate disappear with random mixtures of skin, minerals,

and imaginary textures; the monitor and its objects are perceived in terms of

the material aspects of media. Attaching mirror that reflects surrounding

objects, as well as color plane in geometric shapes, the artist focuses on

formative aspects in what could be seen as an attempt to maximize the flat

surface within the monitor. Intuitive and sensuous, her work has transformed

into an approach where the flood of images in day-to-day life operate as tools

that substitute for language – like images that have been magnified many times

over on a cell phone’s liquid crystal display. This transformation toward a

feedback loop, where the material qualities of material transmit images without

language appearing at the surface level, has the effect of tagging memory and

time in ways that are both more sensuous and more realistic.

Time is present at this moment, but its coordinates are not oriented in any

particular direction. Originating in the personal isolation that she

experienced in a foreign land, Ahram Kwon’s ideas about language and time

create a self-organizing loops that begins from the time and places in which we

live, rather than broadening their reference to the level of cultural spheres

or countries. The disconnection that we experience in words and language at

every moment imitates itself with its endless position tags, without a clear

physical boundary or hierarchy between the real and virtual. And so the artist

looks to consider the time of memory in more compressed, more flattened ways as

it accumulates within a loop of images endlessly exchange through

self-replication. She is considering what comes next, beyond the places and

times where we have been, where we are now, and where we will be.