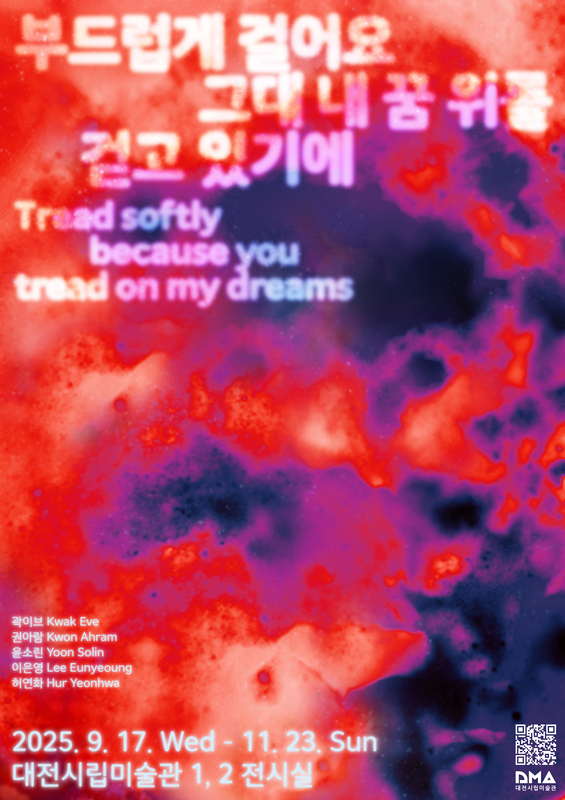

To

refer to Ahram Kwon’s work as “media art” is to categorize it only halfway. As

an artist, the approach she adopts toward the images and texts circulating in

our digitally slanted contemporary communication systems is to present them as

“substance.” Keeping some distance from the experiments with combining art and

technology that were characteristic of video art in the 1960s and 1970s and

have remained part of the visual arts since then, she focuses on the media

themselves—the ones that drive the global circulation of the image. She turns

her attention to multidisciplinary theories of networked media systems,

producing a form of “meta-media” artwork. She abstracts her ideas about media

into images and sound, which she presents primarily on modified screens:

multimedia installations in which acrylic and stainless steel mirrors and steel

pipes and wires are connected to TVs and LED panels.

As the art historian David Joselit has observed, there is an inextricable

relationship between the “media” that power the meaning of digitally based

artistic work, and the “medium” that serves as a support structure for them.

Quoting media theorist Marshall McLuhan’s declaration that the “‘content’ of

any medium is always another medium,” Joselit concludes that the difference

between “medium” and “media” has less to do with their physical characteristics

(painting, sculpture, video, etc.) than with the reaction of those encountering

them.1)

“For in operating on society with a new technology, it is not the incised area

that is most affected. The area of impact and incision is numb. It is the

entire system that is changed. The effect of radio is visual, the effect of the

photo is auditory. Each new impact shifts the ratios among all the senses.”2) Joselit

concludes that the form of media is closer to a ratio (or relationship) between

one medium and another, or between human beings and technology, where he

argues that an “open circuit” operates.

Adopting McLuhan’s media ecology perspective in analytical terms, Joselit

presents a theory of eco-formalism, which uses the analogy to an ecological

system as a way of structuring the process by which information and media

transcend their circulation within the medium that contains them and exert

influence on our reality. He applies the concepts of “feedback,” “loops,” and

“algorithms” to underscore the process of media permeating social institutions

and systems to wield political influence. He also stresses that art should play

a role in providing feedback beyond this insular, internal communication,

opening up a circuit toward reality through diversified identity strategies.

“Learn the system and counter it—make noise. Practice eco-formalism.”3)

Eco-formalism and meta-media

In her 2020 web-based INDEXX,4) Ahram

Kwon presents the media ecology perspective and eco-formalism as an index for

her work. It includes two words shown in capital letters on her screen,

along with 16 keywords such as Hybrudzierung—a

deliberate misspelling of the German Hybridisierung,

meaning “hybridization.” Together with her images and document links gathered

from online, she is sharing clues that link conceptually with her previous

artwork. This non-material work is a sort of “spinoff,” differing from the

materiality explored in Kwon’s multimedia installation work. To give shape to

her worldview in relation to the contemporary social systems in which media and

media function, she expresses connections with multidisciplinary discourses

involving art, philosophy, sociology, and anthropology.

Particularly prominent among her keywords are the name of philosopher Fredric

Jameson and links related to his book Postmodernism, or, The

Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Describing the characteristics of

media, Jameson said that the screen was the flat surface of the image; Flat

Matters (2017), a two-channel video installation by Ahram Kwon,

relates to Jameson not only with its title but also with the context of its

content. The artist’s first TV object work, this installation uses two screens

(combinations of digital screens and mirrors) to alternately show images of

minerals photographed by Kwon, photographs of minerals that she found online,

and images that have been artificially produced or altered. The viewer sees

only the surface image that remains after the actual object has been converted

into a digital image, its volume and textures removed. With the images now

transformed into “substance” at a different layer from reality, it becomes

difficult to discern the differences between them. The core of this work is the

artist’s exploration of her interest in the gap between the real and virtual

that arises when the material world is dematerialized into the digital world,

and her translation of this into the structure of an artwork at the present

moment.

“Materiality” of media

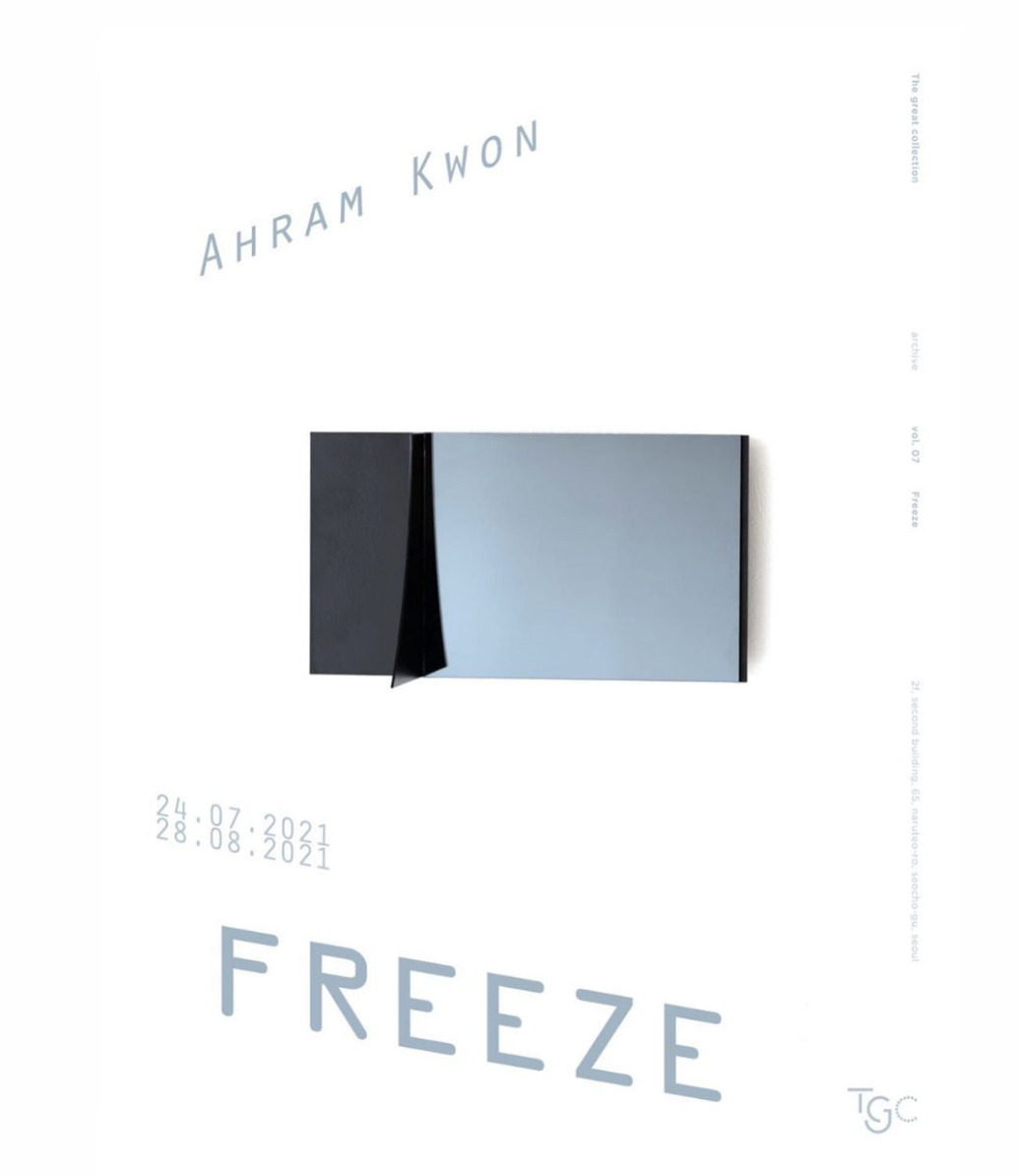

As noted before, what most distinguishes Ahram Kwon’s work from other media art

is her exploration of the screen’s materiality. Since Flat

Matter (2017), which presented its independent screen object

like a work of sculpture, she has expanded into forms that relate profoundly

with the spatial sense of their exhibition environment. She has applied this

strategy consistently with her 2018 solo exhibition Flat Matters at

One and J. +1, the 2019 Nam-Seoul Museum of Art special exhibition The

Unstable Objects, and the Platform-L special exhibition The

Best World Possible.5)

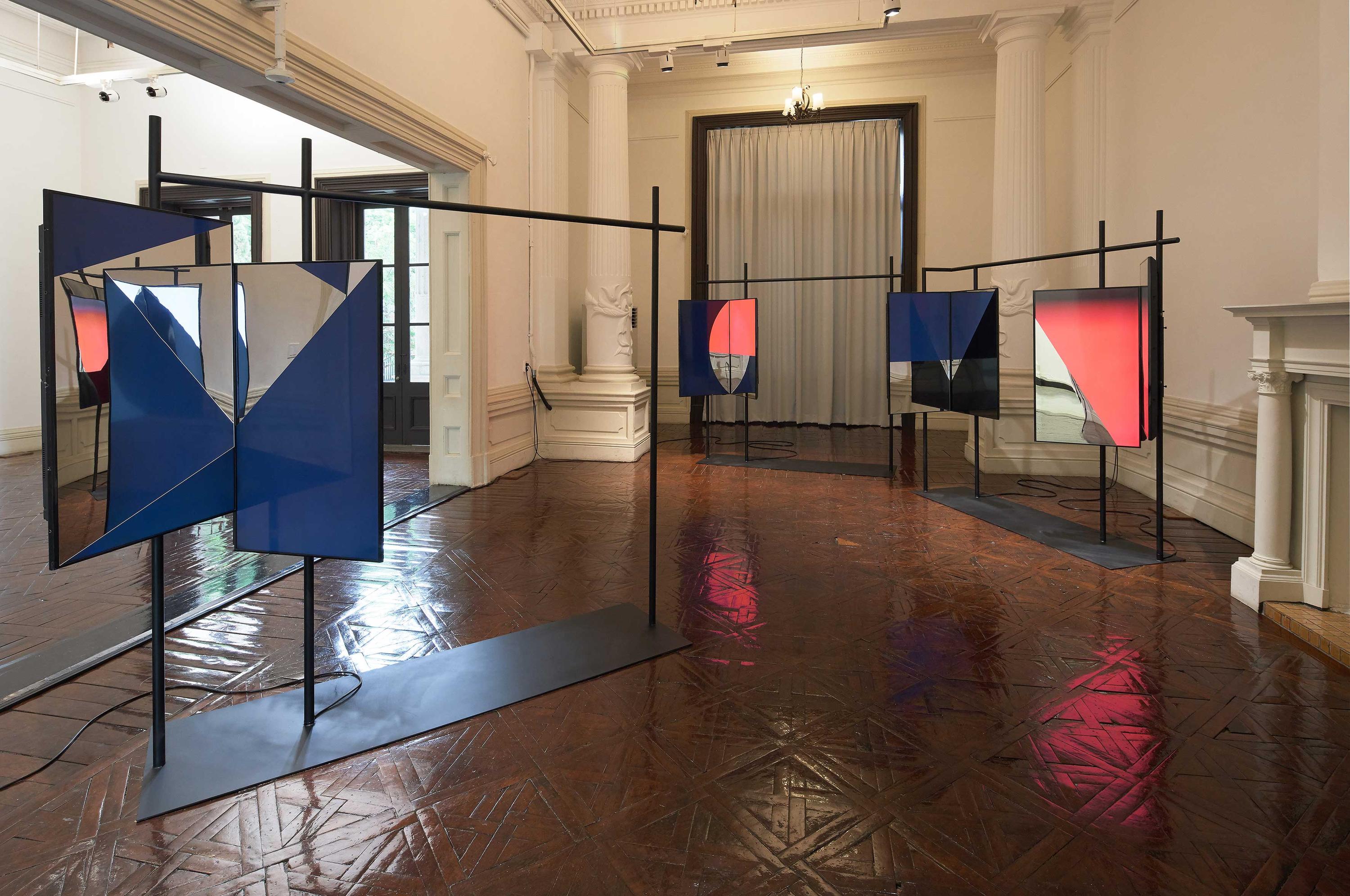

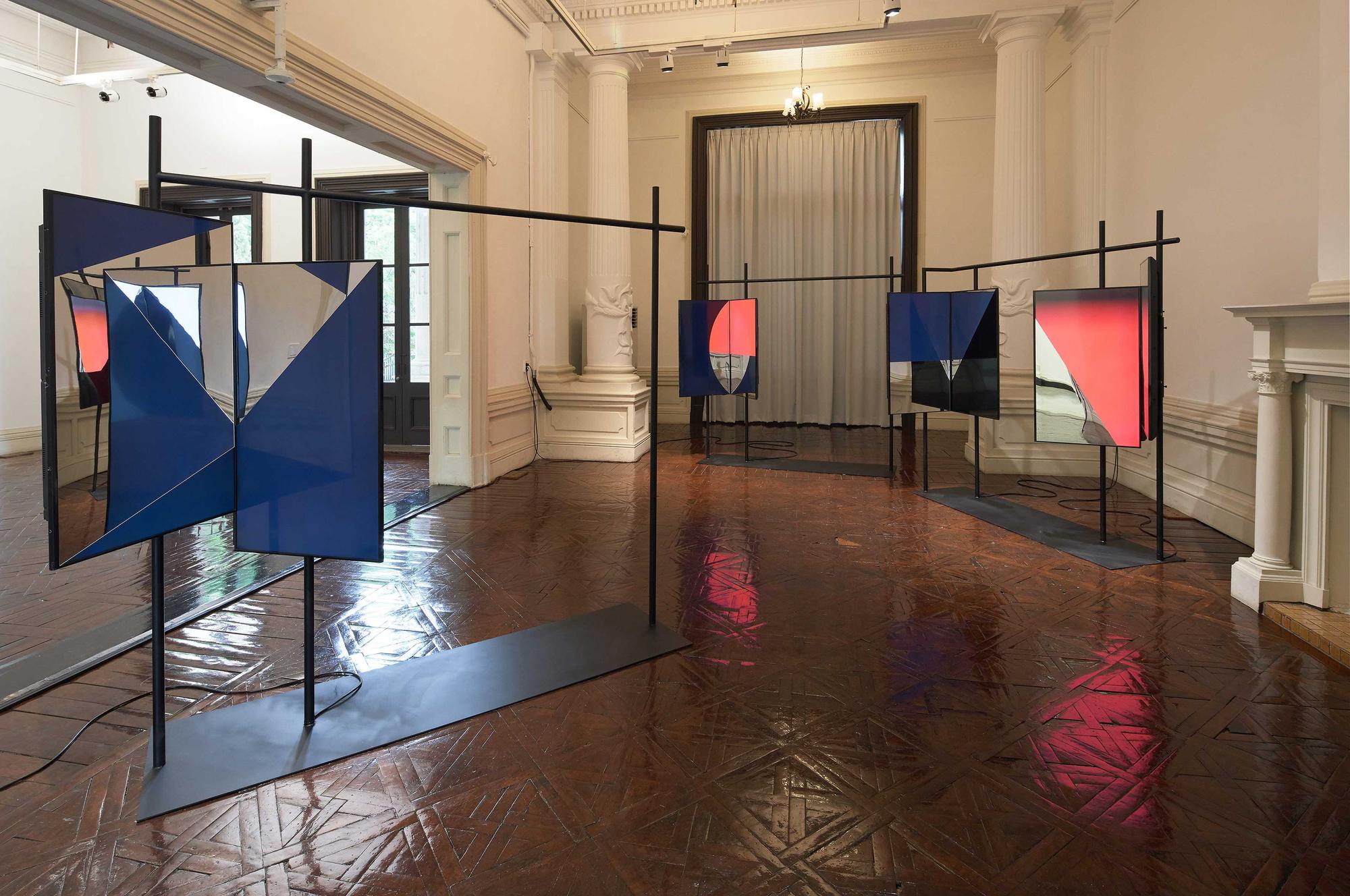

It is in her series Flat Matters (2018) that Kwon

truly decries the two-dimensional and fictitious nature of images that appear

in media. Tailoring her work to the spatial characteristics of the One and J. +

1 gallery setting where her solo exhibition of the same name was held—with its

low ceilings and narrow dimensions—she installed several vertical steel pipes

on the ceiling and walls, fixing several pairs of screens to them to match the

viewer’s sight line. As the pairs of screens radiate light toward each other, a

clash arises between the images on each of them—the red and blue screens.

Acrylic mirrors, trimmed into triangles and squares, are combined with the

screens, so that the color planes become segmented. Through a situation where

it becomes difficult to determine what is a transmitted image and what is a mirror

reflection, Kwon visualizes what has become known as “reset syndrome”: the way

in which we gradually lose our sense of reality living in the “metaverse” of

online environments in the Web 3.0 era.

Ghost Wall (2019) and Invisible Matters (2019),

which were presented at the Nam-Seoul Museum of Art, are divided in space so

that they become something closer to sculpture. The monitor in the

steel-structured Ghost Wall is no longer an

ordinary home television screen—instead, it appears as a radiant performer.

For Invisible Matters, the mirrors previously placed

on the screen are now installed on the gallery floor, which both draws

attention to the screen’s mass and centrally visualizes the mirror’s inverted

image. This approach of giving more or less equal weight to the screen’s materiality

and the video’s illusion evokes associations with a real world environment

where commodity fetishism is barreling toward extremes both on- and offline. In

expressing her critical stance on media at a meta level, Kwon realizes an

aesthetic that becomes a mechanism guiding our thought toward the “medium”

support structure itself, rather than the technology. This is, of course, a

strategy for showing the fetishistic and commercial aspects of the screen

itself. The artist explains:

“As I incorporated concepts of media theory as key content in my work, I made

use of the characteristics of reflection by the mirrors and screens. I felt

that the relationship between the work’s form and content was similar to the

principles of image production by media, which is an area of interest for me,

or to the ways in which media companies reveal their ulterior motives.

Through artwork that is cut as if with a knife and composed in lucid colors, I

am able to conceptualize this hidden meaning of media objects that manipulate

societies and people behind the scenes.”

Politics and malfunctioning

In this way, Ahram Kwon’s work is structured into forms rooted in a critical

perspective on the politics of media. This aspect appears to more dramatic

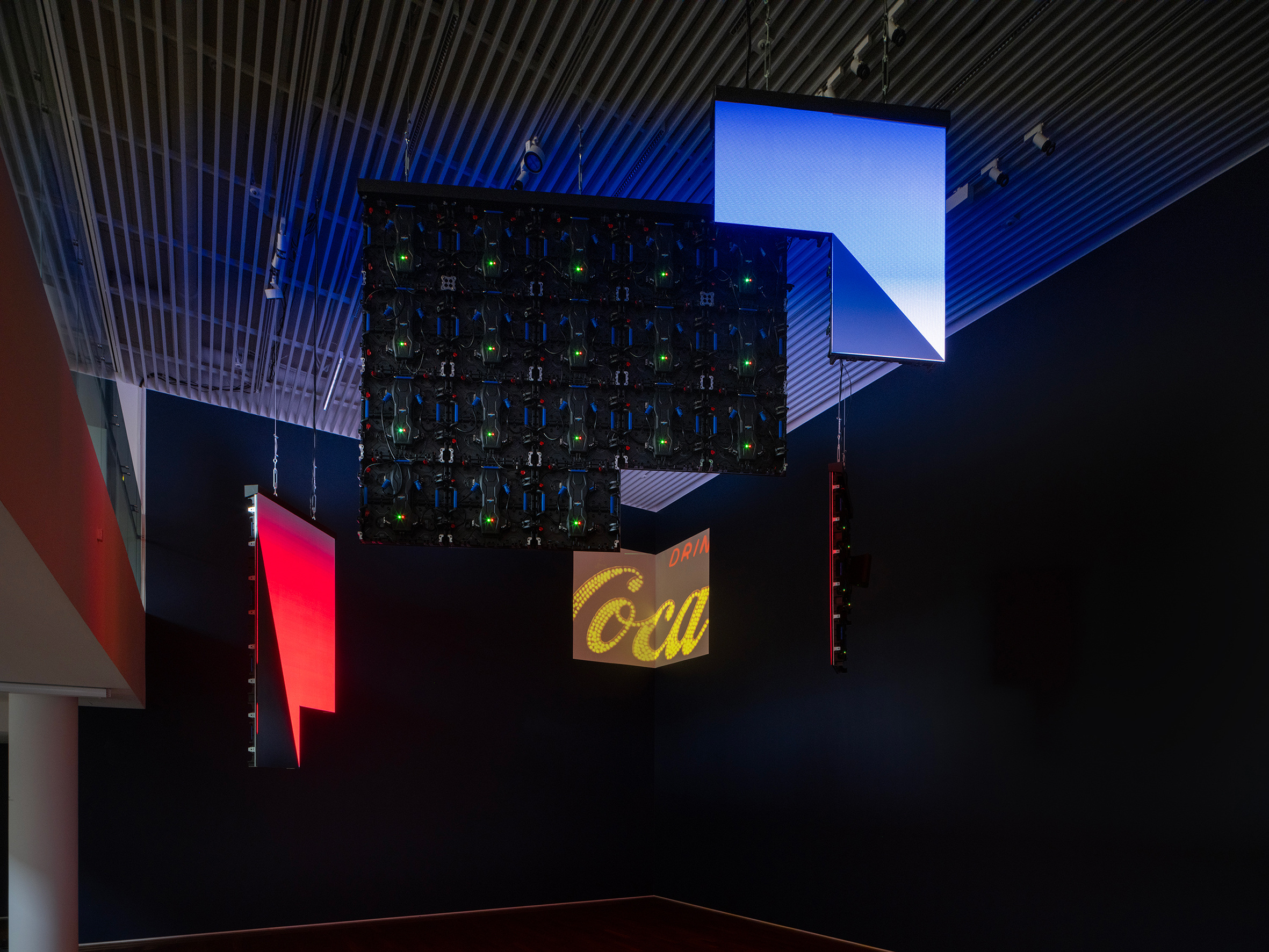

effect in Walls (2021), for which she won the grand prize at the 2022

SongEun Art Award. In late 2021, the gallery at the new SongEun building

designed by Herzog & de Meuron was filled with new work by 20 young

artists, spread out across three floors. Kwon was assigned a space near the

center of the gallery on the second basement level. Making use of the high

ceiling there, she attached steel wire to the ceiling and connected it with

four large screens, giving the appearance that the screens were falling through

the air. For the first time, she used LED panels instead of TV monitors; these

materials are commonly encountered today in large electronic displays in the

center of Seoul. Using square panels as her basic units, she combined them

irregularly in horizontal and vertical dimensions. To these she attached

acrylic mirror that had been trimmed into isosceles triangle and rectangle

shapes. Red and blue screens with different sizes, angles, and proportions

blink on and off, mixing with the sounds of mouse clicks and ventilation fans.

At the rhythm of image and sound speeds up, the blue and red screens give off

an ominous sense, creating a vast vortex that alternates quickly among the

different screens. Suddenly, it gives way to a pixelated screen, as if

signaling some kind of signal error. With a beep and the sound of static, the

images disappear from the four screens.

Kwon explains that she was “curious whether I could communicate a micro-scale

message that corresponded on equal terms with the powerful spatial sense of the

exhibition setting.”6) Even as she enhances the scale and

resolution of her screens, she makes sure that the viewer’s spectacle never

goes beyond ordinary eye level (in contrast with the towering perspectives of

media walls). This allows the viewer to commune physically with the work at a

close distance. The familiar sound of a mouse click and the audio-visual

pattern of the blue screen dramatically repeating and expanding represent what

Joselit defined as the “viral” properties of media. The broken pixel images that

permeate the real world by way of the screen may be interpreted as a strategy

for critiquing or neutralizing the media’s careful targeting of (prospective)

consumers in capitalist society. In this respect, Kwon’s media sculptures are

no longer merely meditative rhetoric; they take a step forward from her past

work as signs of a political nature. Capturing both the human desires contained

within media as well as the errors of media—which seem to answer our

expectations but only end up malfunctioning—she underscores the illusory nature

of spectacle in the digital world.

Creating ready-mades out of the media that stimulate our desires by way of the

screen, Ahram Kwon sees possibilities for liberation in the functional

constraints of devices, as symbolized by their malfunctioning. “The screen

turns into a wall the moment its power is disconnected; as soon as the

particles are activated, it becomes a conduit through which human beings

project their desires,” she explains. “Just as there are principles of capital

and the economy and relationships of production and consumption operating

behind the image in its sleek product packaging, I am alluding to the errors

[of media] by means of a handful of clues.”7) Kwon has just

begun making concrete statements about the capitalized media that chip away at

their users in the name of “communication.” I look forward to observing how her

meta-media sculptures develop in the future into interactive practical forms

that actively connect reality to the insular experience of media.

1) David Joselit, “Open Circuits,” Feedback: Television against

Democracy, Korean trans. An Dae-woong et al. (Seoul: Hyunsil Munhwa, 2016),

63–64.

2) Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of

Man (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1964/1996), 64; quoted in Joselit.

3) Joselit, “Afterword: Manifesto,” 246.

4) https://indexx.ahramkwon.com.

5) Conversation between Tiffany Yeon Chae and Ahram Kwon for a program

associated with the Seoul Museum of Art Nanji Residency’s Open-Source

Studio, Dec. 31, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zU8KvJiVIPA.

6) Interview with the artist, March 9, 2022.

7) Interview with the artist, Vogue Korea, March 2022.