Solo Exhibitions (Brief)

An’s recent solo exhibitions

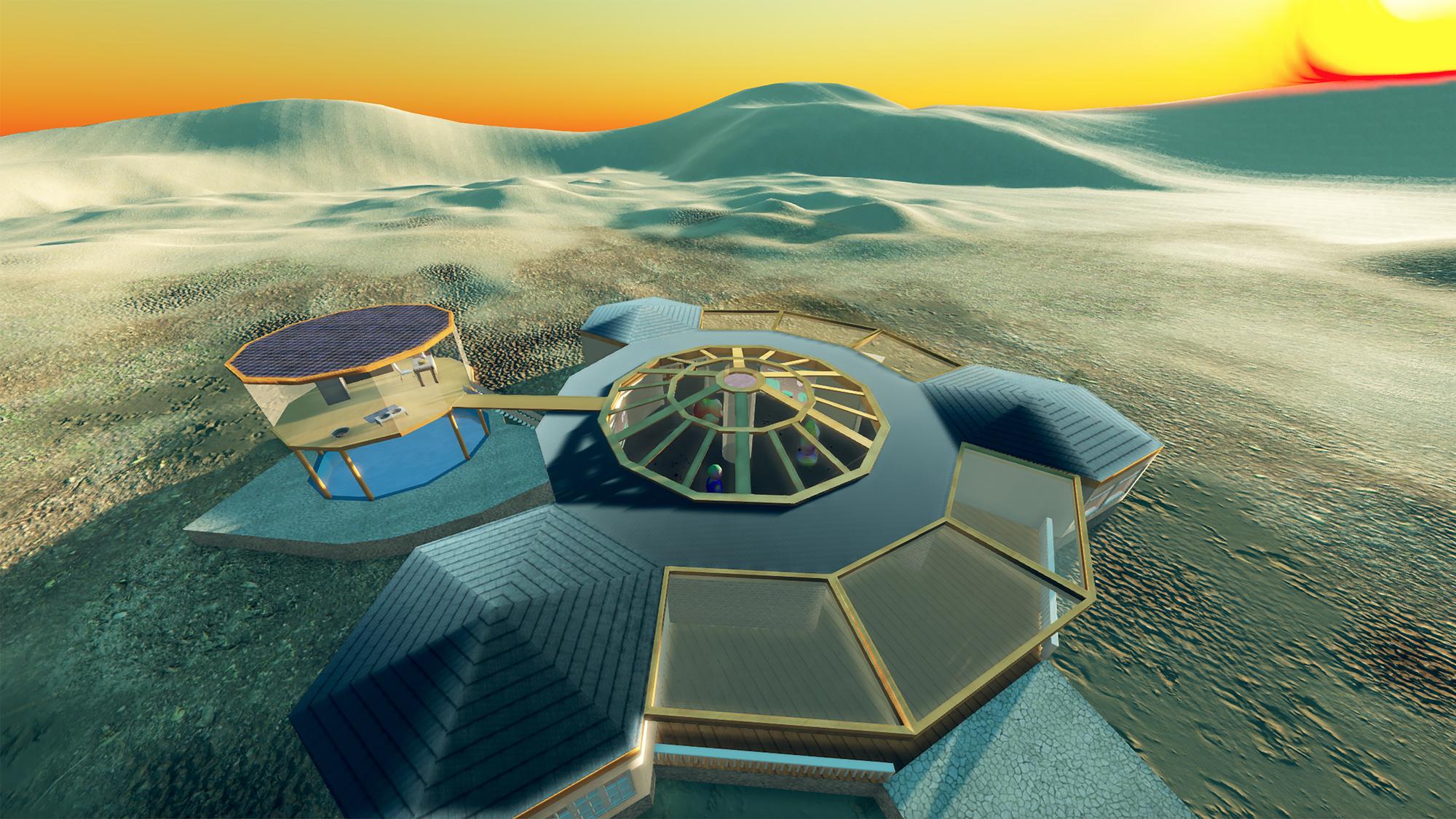

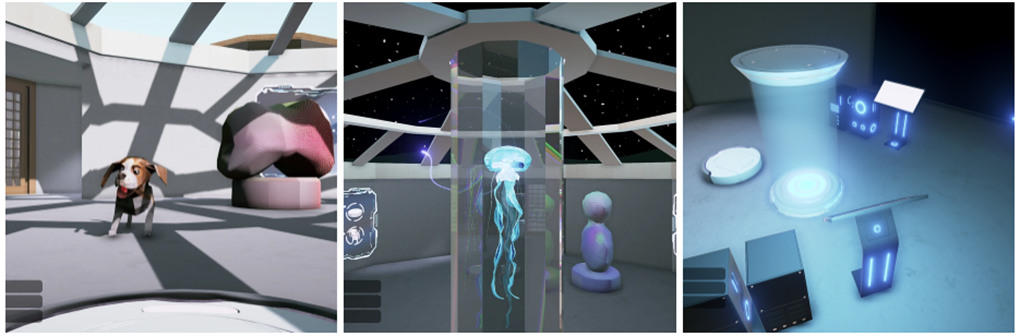

include 《COSMIC SENSE: XR Simulation for Humankind of the Future》 (Coreana Museum of Art, Seoul, 2022), 《Iridium

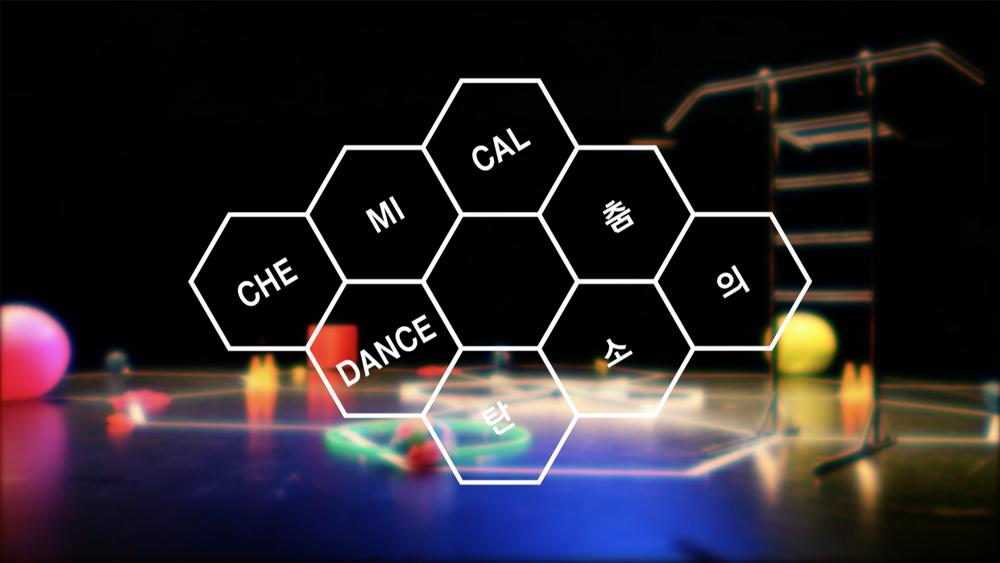

Age: Making New KIN》 (Seongbuk Children’s Museum,

2021), 《KIN in the shelter》 (Artist

Residency Temi, Daejeon, 2019), 《Lazy teleport》 (Art Space Jungmiso, Seoul, 2016), and more.

Group Exhibitions (Brief)

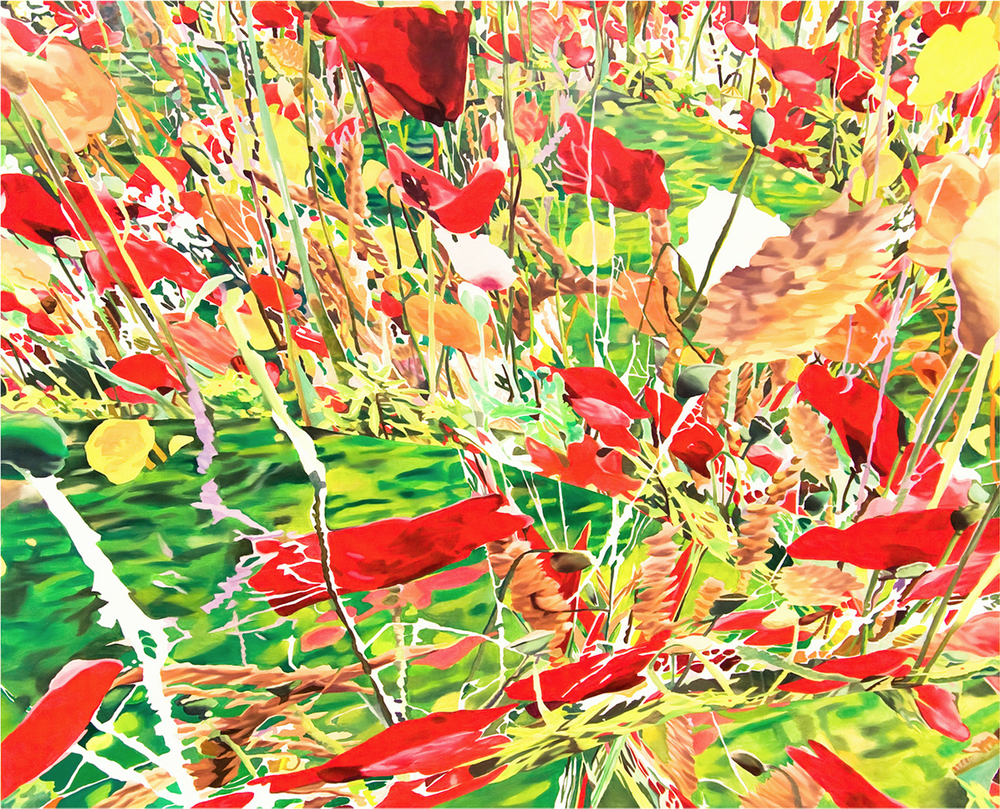

An also has participated in numerous group exhibitions, such as 《Project Hashtag 2023》 (National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea, Seoul, 2023), Digital Art Festival Taipei 2023 《A-Real Engine》 (Digital Art Center, Taipei, 2023), 《Future Fantastic》 (Art Center Nabi, Seoul, 2022), 《The Most Brilliant Moments for you》 (Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, Ansan, 2022), 《ONOOOFF》 (Busan Museum of Art, Busan, 2021), and Gwangju Media Art Festival 《Algorithmic Society》 (National Asia Culture Center, Gwangju, 2018).

Awards (Selected)

An has received a prestigious awards, including

the Emerging Female Artist, 15th Gender Equality and Culture of the Year

Award in 2022.

Residencies (Selected)

An has been selected as an

artist-in-residence at the SeMA Nanji Residency (2025), MMCA Residency

Changdong (2023), MMCA Residency Goyang (2022), and more.

Collections (Selected)

An’s works are part of the collections of the Daejeon Museum of Art, the Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, the Seo-Seoul Museum of Art, the Embassy of the Republic of Korea to the Republic of South Africa.