When we ask what a work of art contains, we are essentially

describing art as a kind of vessel. Naturally, the contents of the vessel are

then regarded as the artist's inner world or a message directed at the

audience, and there follows an assumption that the artist must always dutifully

fill that vessel. For audiences who prefer a vessel filled with rich content, a

bad work of art is thus considered an empty one—a hollow vessel—or,

simultaneously, one that merely “looks like something,” a deceptive vessel.

However, the fullness an audience experiences in front of a work

is not granted easily. It can only be attained through the act of thoroughly

wandering and circling the interior surface of that vessel. Expressions such as

“I read through the text carefully” or “I walked around that exhibition”

metaphorically operate as deep metaphors for such acts of exploration. Rather

than staring at the contents of the vessel statically and all at once, one

examines and traverses it over time—turning the experience into a journey on

foot. In this sense, an insincere viewer of art is one who may move around, but

does not firmly place their feet on the path. In other words, they are someone

who drifts aimlessly, or pretends to know without ever having explored—the

deceptive walker of paths.

In truth, much of everyday language is metaphorical, and as Lakoff

and Johnson argued in the 1980s, these metaphors are guided by a few

fundamental source domains. They proposed that human behavior is shaped by

powerful deep metaphors like “vessels” and “paths.” In this way, the vessel

(the artwork) and the act of walking (the viewer) strive toward fulfillment

through mutual effort. These deep metaphors appear across virtually all

languages. At the same time, we find that they also function as recurring grammatical

elements within the worldview of certain artists.

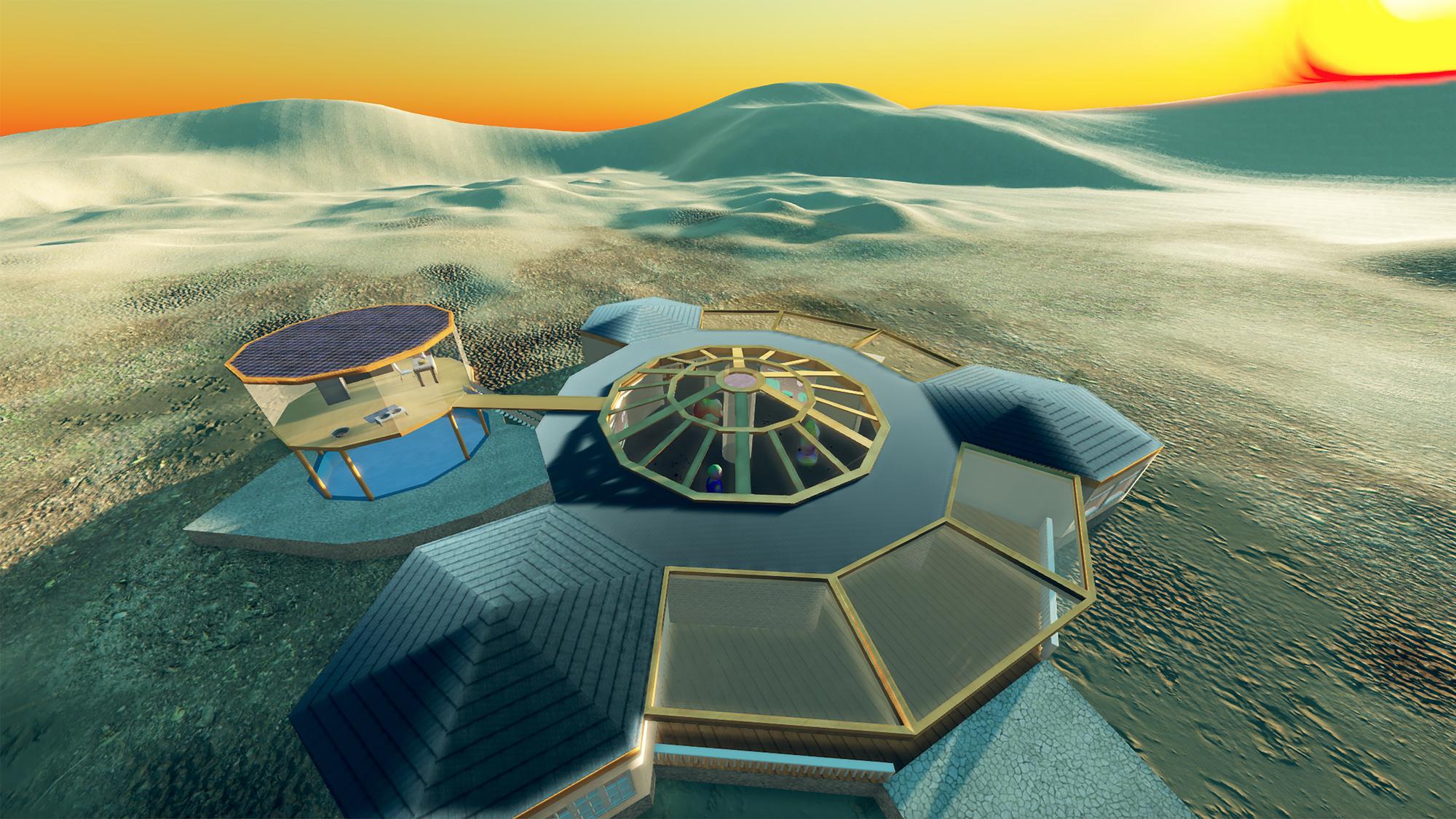

One of the most prominent features of An Gayoung’s practice is her

proactive adoption of game engines as a new kind of brush and canvas to

construct her virtual and interactive worlds through networks and code.

Commentary that has followed her work includes statements like: “Perception and

internet network environments are critical themes in contemporary art” (Jinsil

Lee, 2019), “[Her work moves between] cyber-determinism and cyber-contingency

in algorithm-constrained cyberspaces” (Eunsun Yoo, 2014), “Falling into the

labyrinth of ‘the network,’ and retrieving something within it” (Yoonhee Jung,

2016), and “A game-like space filled with non-human objects” (Junhyoung Ahn,

2021). What these interpretations share is the observation that her work

constructs virtual spaces through game-like structures and emphasizes

exploration within them.

Her 2016 work The Hermes’s Box marked a

definitive turn in this direction. The piece portrays the ironic narrative of

Hermes, tasked with delivering a parcel for Zeus, who ends up lost—and in the

act of getting lost, must begin a new process of finding a way. Unlike

conventional game mechanics that reward players only when they follow preset

quests, this work engages a paradox in which one must get lost in order to find

a path. The audience is invited to wander directly, using a joystick. From the

artist’s side, An Gayoung declares: “We were Hermes.” In contrast, Worlding

(2018) was a work that dreamed of a small open world designed to accommodate

more creative disorientation. This open-ended spatial design has evolved in

tandem with the growing computational capacity of improved game engines. At

this point, we must admit that we do not yet fully know what the artist intends

to express—because sometimes, it is technology that becomes the trigger

releasing the artist’s desire.

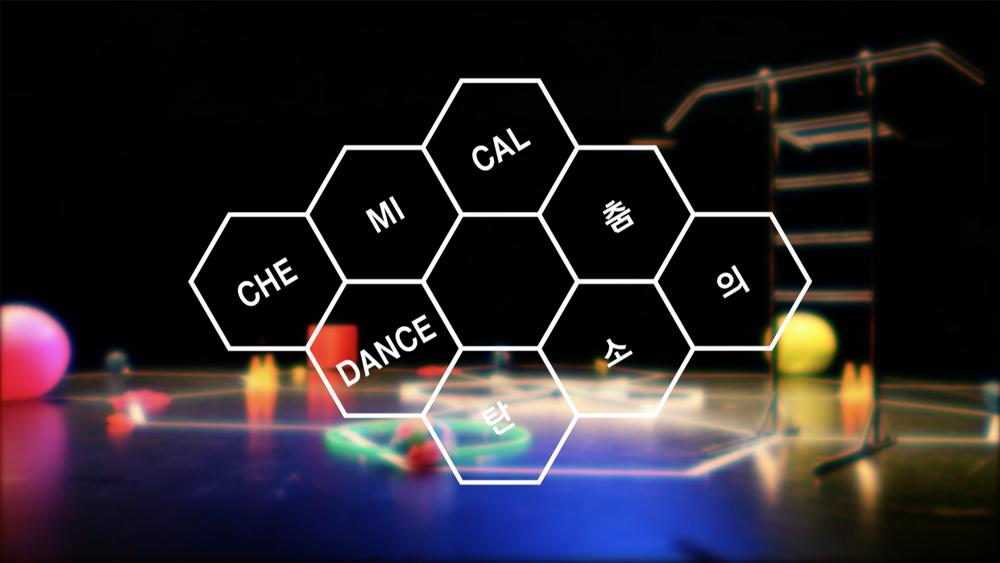

The KIN trilogy—KIN in the shelter: Beta

(2019), KIN in the shelter: Online (2021), and KIN

in the shelter (2021)—incorporates various technical elements such as

simulation games and multiplayer avatar chatting systems. At a moment when

daily life was shut down due to COVID-19 and solitary individuals began diving

into cyberspace, An Gayoung introduced a turning point via metaverse platforms

like VRChat: a transition from getting lost alone to getting lost together with

others. What do these players, who get lost creatively as a group, actually

look like?

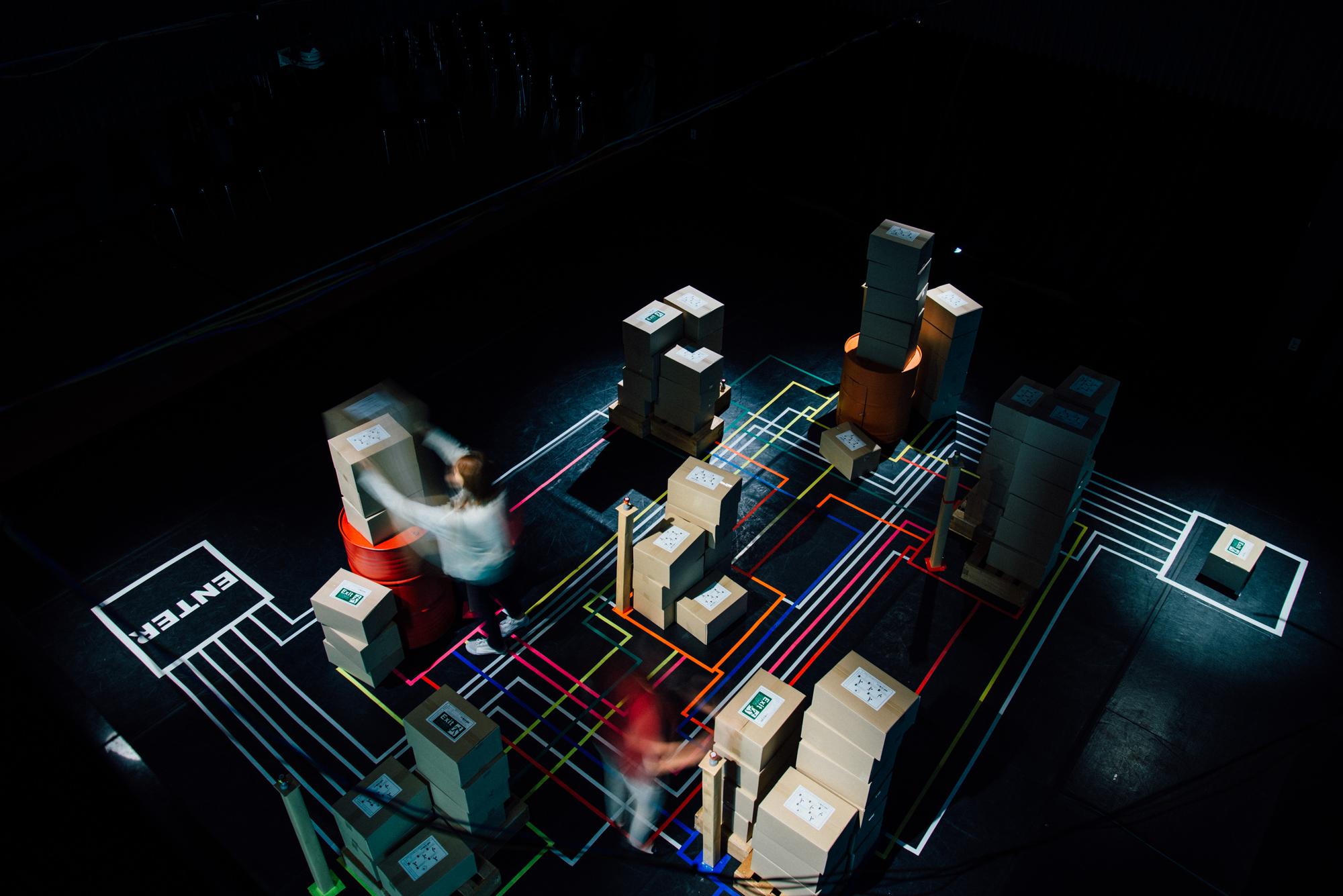

In KIN in the shelter: Online (2021), they are

in fact those who have been excluded or expelled from existing virtual worlds.

Ji-hye was designed with voluptuous curves to appeal to male gamers, but once

her commercial value was lost, she was discarded like data waste. Min-ji tries to

enter the virtual world from the real one, yet fails to even press the control

buttons properly—she is immobile. Hye-ji is a digital laborer whose carefully

crafted avatar is easily stolen by others. These figures are lost or even

exiled within online spaces that remain tightly bound to the realities of the

offline world.

But they are not merely taking refuge in the online shelter. They

are conspiring, planning a counterattack. Ji-hye eventually undergoes plastic

surgery in cyberspace, arming herself with enormous wings and missiles. This

image recalls Dr. Frankenstein, who sewed together a new being from scattered

body parts. But unlike Frankenstein—who abandons his creation—An Gayoung helps

this new being claim her twisted language not as an error, but as her own

voice. The 21C Cyber Body Liberation Manifesto (2020), which

the artist has long advocated, is not about escaping into cyberspace, but

rather about escaping from the current conditions of cyberspace itself.

KIN in the shelter (2021) features three

characters: Mei, a cloned dog sent from a drug detection unit to an animal

testing lab; Joon, an outdated cleaning robot who lost his job to a newer AI

vacuum; and July, a migrant laborer exposed to toxic materials at a power plant

whose skin has turned green like an alien. These three characters resonate in

parallel with Ji-hye, Min-ji, and Hye-ji from KIN in the shelter:

Online. The key difference is that while Ji-hye, Min-ji, and Hye-ji

represent cyborgian assemblages of humans and virtual technologies, Mei, Joon,

and July are non-human or nearly non-human beings.