The 2018 F/W “Ready to Wear” fashion show by the Italian fashion

house Gucci generated much controversy on multiple fronts. The show was

overshadowed by a backlash surrounding a balaclava turtleneck sweater

resembling blackface—a symbol of anti-Black racism. Even Black rappers, who had

popularized “Gucci” as a synonym for stylish and cool, turned their backs on

the brand. While this instance of racial insensitivity from a high-end brand

drew public attention, less noted was the show's inspiration from Donna J.

Haraway’s A Cyborg Manifesto (1985), incorporating

genderless and posthuman approaches with icons from medieval mythology such as

dragons, demonic horns, and the eye of the Cyclops. Particularly striking was

the imagery of a model walking down the runway holding a replica of their own

head—a visual reminiscent of a cephalophore.

The cephalophore, meaning “one who carries their head,” is an

image with a long historical lineage. The headless horseman in The

Legend of Sleepy Hollow (1820) is a popular figure, whose origins can

be traced back to the Irish and Celtic myth of the Dullahan. In Christian

iconography, the cephalophore often appears in narratives of martyrdom and war.

Judith beheading Holofernes, David raising Goliath’s severed head, Medusa, and

the decapitated head of John the Baptist—these are all motifs frequently invoked

in moments of dramatic intensity. A key cephalophoric figure is Dionysius, also

known as Saint Denis, the patron saint of France. Around the 3rd century CE,

before Christianity was officially recognized, Dionysius was captured while

preaching in Paris and executed by beheading on Montmartre. According to

legend, after his execution, his decapitated body lifted his severed head with

both hands and walked approximately five kilometers before stopping—at which

point the Basilica of Saint-Denis was later built.

In Christian iconographic tradition, saints are often depicted

holding objects symbolizing their identity—keys to heaven, scriptures, or

instruments of their martyrdom. Bartholomew, flayed alive, is shown holding his

own skin; Saint Agatha, whose breasts were severed, carries them on a silver

tray. Dionysius, beheaded, holds his own head. Decapitation as a form of

execution was practiced in both the East and West; in Korea, during the

Byeongin persecution of 1866, Catholics were beheaded en masse on Yanghwajin,

later nicknamed the “Mountain of Severed Heads.” Yet this is not merely a

symbol of religious persecution. Searching “cephalophore” often reveals icons

with haloes in various positions—sometimes illuminating the severed head held

in the saint’s hands, sometimes radiating from the empty space left on the

neck. This suggests a range of interpretations regarding the relationship

between soul, body, and head.

Beyond religion and myth, the motif of the severed head has made

appearances in more recent times in Japanese animation, such as the cyborg

Count Brocken from the Mazinger series, and Zeong, a robot in Mobile

Suit Gundam, both of which emphasize decapitated forms.

The cephalophore iconography seems to have gained popularity for

its grotesque fascination and as a sign of saints overcoming death. However, if

we accept the condition of bodily separation, the head alone cannot function

independently. Is the head subordinate to the body, or the body to the head?

Since neither can function alone, the head must ultimately exist as an image—as

an icon. The first icon and image of God is considered to be the face of Jesus

imprinted on Saint Veronica’s veil. According to tradition, Saint Veronica

captured the face of Christ on her cloth, creating the first, most direct image

of the Son of God. Another example of the head existing as a complete form is

the cherubim—typically portrayed as a baby’s head with wings. Though grotesque,

it symbolizes a being close to the divine, complete in itself and not severed

from a body.

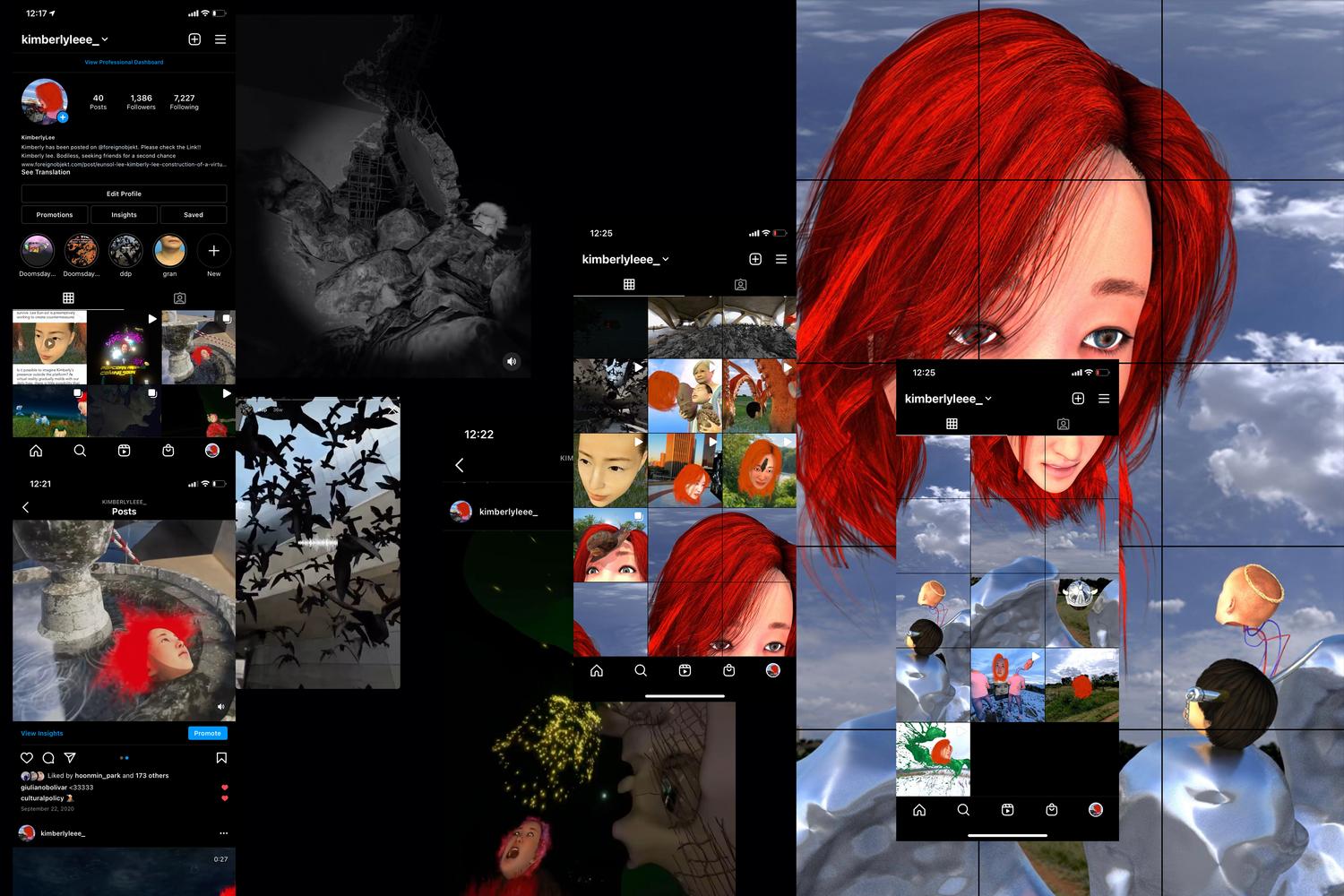

In the virtual space created by Eunsol Lee, Kimberly Lee exists

solely as a head, without a body. This floating being, defying gravity, spends

time in fountains and bathtubs, draws magic circles, or becomes embroiled in

mysterious events, thus forming a kind of multiverse. Within the designated

environment, Kimberly functions as an independent and complete entity. The

artist continues to develop a series of projects to sustain Kimberly’s

existence and imbue her with vitality. However, claiming Kimberly is complete

in herself is fundamentally contradictory. If we consider physical reality as

the body, and virtuality as the head, then Kimberly cannot function

autonomously. In the video work I want to be a cephalopod (2021),

Eunsol Lee metaphorically explores Kimberly’s existence through a dialogue

between two head-only characters about soul and body. The video references

traditional soul theories and the controversial experiments of Robert Joseph

White, who conducted head transplants on monkeys, to discuss the relationship

between the head and the body.

Today, intangible assets such as Bitcoin and NFTs command high

value and influence real-world economies, while the metaverse allows people to

perceive physical and virtual infrastructures as equals. These phenomena are

not unlike many historical instances where unprovable entities were imbued with

sanctity and made real. Kimberly is now preparing to optimize herself for

survival and adaptability across diverse platforms. And I reflect on the

strange lightness of the weight of a single head.