A radical does not wait to be appointed from the outside but acts.

The idea of radicalism is never fully realized, yet a true radical—that is, an

artist—unceasingly declares. An artist's declaration is not measured by actions

that prioritize words. It is not about exhausting one's existence to amplify

existing voices. Rather, the artist works. This may be a prolonged time of

uncertainty, where the visibility of efficacy takes a long time, and even the

essence of effect remains ambiguous. Everyone equips themselves with their own

beliefs for practice, but often, they are soon ensnared by false consciousness,

facing difficulties that arise moment by moment. Nevertheless, the reason we

anticipate scenes longing for the achievement of radicalism is that it is the

only intriguing hope. Therefore, in the interest of the artistic practice that

the artist aims for, TZUSOO deserves the highest superlatives.

Parallel Fictions with Predicted Cycles

TZUSOO's world is both total and fragmented. There is no priority

between the two. In fact, naming totality and fragmentation as opposing

elements may itself be a misreading. For instance, Aimy, created by TZUSOO,

exists. At this point, TZUSOO holds the contradiction of being 'actually a

mother' and simultaneously 'not a real mother.' On the one hand, the assumption

that Aimy could be a part of TZUSOO is valid, but the proposition that TZUSOO

could be Aimy is not. Then, what kind of being is Aimy? Here, several

'conscious appropriations of negation' are required. Aimy is not pure but is

not defiled either. She does not need a father. Her physical size within the

world is unknown. During the 'day,' she works as a producer and

singer-songwriter named 'Aimy Moon,' creating AI music. This work is a pure

activity, not labor as a means for capital. She has no bodily fluids and does

not excrete. She does not eat food but has drunk alcohol when nervous. She has

no body temperature but has felt cold when entering water. She never ages, but

considering the pace of technological advancement, she sometimes feels

nostalgic. In short, Aimy implies a negation from the human but provides a

cheerful confusion in that it is not a complete negation.

In addition to the confusion, TZUSOO has relatively clearly

divided Aimy's spaces. Aimy Moon wears a wig, applies makeup that seems lively

yet shy, wears a short skirt, and sings with a mysterious and youthful voice.

Her singing ability is unquestionable and always safe. From optimistic lyrics

to instantly gratifying choruses, the composition as typical K-Pop music is

impeccable. Thus, Aimy Moon appropriates the totality of 'female-being,'

encompassing music, clothing, and voice of female idols. On the other hand, the

melancholic activist Aimy, who has 'clocked out' from 'work,' has a voice whose

gender cannot be discerned. Cheerfulness seems never to have existed, and there

is a somewhat cynical aspect. With a shaved head and a bare upper body, a

piercing is evident on the right nipple. The beginning and end of the space are

ambiguous and infinite, and she floats endlessly in a somewhat depressive void,

existing only in the present.

These two are completely separated not only in the spaces they

inhabit but also in attitude, personality, and audience. This means their

communities and timelines are entirely different. However, only TZUSOO is the

sole link and possibility of connection between the two. Another interesting

point here is that those who become fans by listening to Aimy Moon's songs and

those who view Aimy in art museums without knowing Aimy Moon's existence are

all 'humans who are material somewhere, opaque, and thus cannot be fluid.'

Humans, as temporary masses within the world, are connected through Aimy.

Anyone can establish their own relationship with Aimy and derive meaning. As

connections are activated, Aimy, conceived and created by TZUSOO, gains

autonomy in itself. TZUSOO gave birth to Aimy but cannot fully grasp Aimy's

inner thoughts. This truth accelerates Aimy into the realm of radical autonomy.

This is one of the true joys that art can achieve. TZUSOO creates beings,

proliferates them, and circulates the way of contemplating systems. The fact

that one can circulate systems in a reversible world that does not easily mix,

not through words but through practice, is an undeniable wonder.

The Freedom of Genderlessness

“The cyborg does not dream of community on the model of the

organic family, this time without the Oedipal project. The cyborg would not

recognize the Garden of Eden; it is not made of mud and cannot dream of

returning to dust.”

— Donna Haraway, A Cyborg Manifesto, “A Cyborg Manifesto:

Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century”

(1984)

If there is no Oedipal project, what purpose does gender serve?

Gender opposes the cyborg. It divides rather than unifies. To overcome the

contradictions of gender, we need an entity that can be “everything.” Being

“everything” means not being named by any existing classification. Applying

classifications is quite challenging because existence itself is history, and

the observer also possesses their own history. Thus, the past inevitably

invokes classifications—unpleasant and inaccurate. Artists always aim for

creations unbound by such constraints. When this aim is fully realized, the

creation gains the potential to live as a universal entity, transcending time.

Similarly, TZUSOO's approach to gender leans toward a state that

opposes gender distinctions. It is not a freedom achieved through struggle and

naming but a greater freedom attained by relinquishing naming. This

renunciation is not an escape into a world of mental comfort but the courage to

confront reality head-on.

In this light, TZUSOO's work goes beyond metaphorically

representing a state of freedom through visual culture; it constructs a world

of freedom itself. This world is open, anonymous, and uncertain. The Garden of

Eden, with its knowledge of good and evil, is inherently a concentration of

morality and ethics. The desire for Eden encompasses all the systems that

constitute our current society. For instance, to return to paradise, one must

repent for original sin and choose not to sin again. From this point, all

violence in the world is justified. Therefore, Eden is not a land that promises

true freedom but a provisional reward offered only to those who survive

repeated exclusions.

TZUSOO's world deliberately discards the classical perception of

Eden's existence. The character-cyborgs in her work, as “ether” and

“quintessence,” do not appear as means to oppose existing norms but exist by

not knowing the existence of norms from the outset. Then, what kind of

transformations do they undergo in their social/physical realities? Are these

transformations predictable?

How Not to Become Human

At some point, TZUSOO stated, “Physically speaking, humans cannot

have free will.” The absence of free will is a physical truth, but from the

perspective of the subject accepting it, it remains contentious. Moreover, in

the field of art, where individual choice is highly valued, this deterministic

foundation easily clashes. So, how do TZUSOO's views on free will align with

the autonomy of the entities in her art and her own artistic freedom? What does

artistic choice mean when made with an awareness of determinism? Whatever form

it takes, it must differ from choices based on optimistic beliefs in free will.

Determinism is a major truth that can dishearten humans, especially artists,

but confronting this truth enables artists to accept and recreate it, making

creation possible.

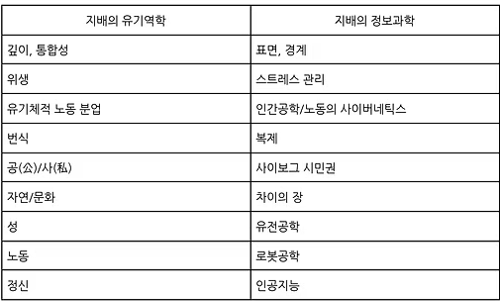

In this context, Donna Haraway provided a prophetic diagnosis

through the following diagram: