Rotating Video Prison = Me

Hyojae Kim’s 《Default》 (2019) presents a taxonomy of human beings. Or perhaps it

demonstrates how humans touch each other today? While screens—monitors and

smartphone displays—take care of how humans look at one another, the number of

centimeters we should set between each other’s footsteps has not been

determined. As a result, we’ve forgotten how to touch each other. Is YouTube

solely to blame for this? What’s clear is that long before YouTube and

smartphones began consuming our souls, there were already systems like the four

pillars of destiny. But the very way we sense human existence has changed. In

other words, it is a hypothesis that belief in the invisible was not always as

powerless as it is now. In Kim’s videos, solidified images dance rhythmically.

In a state of maximized motion and activation, the sound in Kim’s work serves

as a hallucinogen, never ceasing, striking the floor so it won’t harden. The

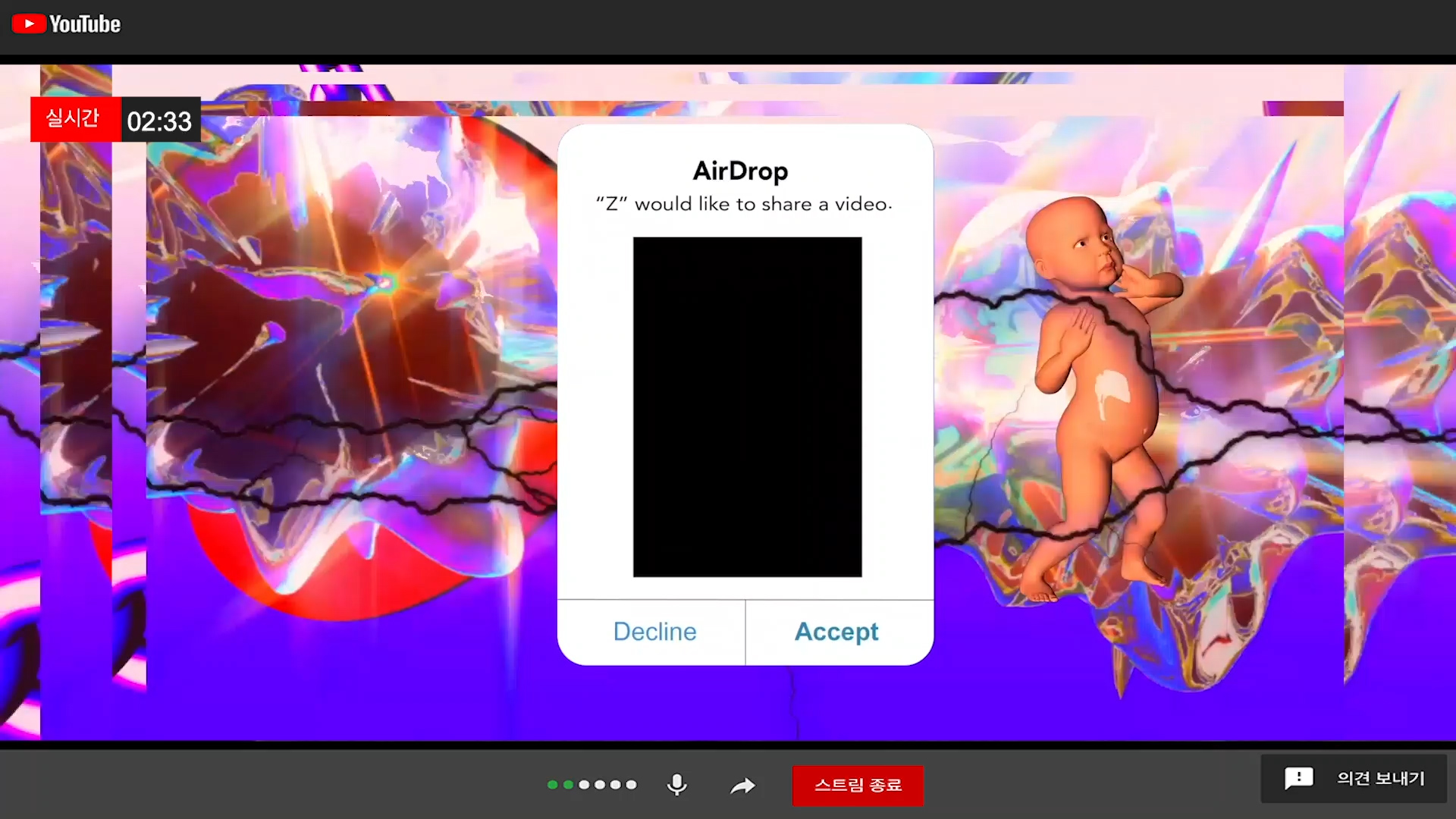

three videos—〈SSUL〉, 〈Z〉, and 〈UNBOXING〉—produced by the artist are “rebellious substitutes” for one

another. They don’t perfectly replace each other, but they become each other’s

broken mirrors, shattering the old metaphor of inversion or backside, and

forming a triangular composition. Rebellion (betray)—the fact that people can

screw each other over so easily, leave comments, and log out to cut ties—has

become a cliché of everyday life. Depending on what coordinates are inserted

into the horizontal and vertical axes of this triangle, the objectified human

form rushes toward a 360-degree revolving perspective. What recurs in Kim’s

work are stream terminations, button frames, and the phrase “Ad will play

shortly.” While the video says it will “start after the ad,” this temporal

pause is not so different from the time that actually follows. That is to say,

ads replace reality, and reality replaces the unreal, causing the criteria for

judgment to wobble, regardless of generation, era, or physical ownership of a

human body.

Where is the standard? This default short clip persists, and in

the videos, we see Baby Z doing a robotic dance (〈Z〉), and hear the distorted narration of

influencer Kim Nara (@naras._) (〈SSUL〉). The crucial point is that background and figure are no longer

distinguishable. The humans summoned by Kim undergo continuous transformation,

moving between subject, possessive, and objective cases. If transformation

occurred only once, it might carry meaning—but once it becomes repetitive and,

as Kim warns, clichéd, what proliferates is only the empty shell of a stand-in

subject, like a figurehead. Who owns whom? Each speaks of their state and keeps

moving, but nothing seems to truly matter. What the artist presents is a

spiral, revolving temporality and spatiality. I replay these videos multiple

times on my home computer and smartphone, thinking about Hyojae Kim, the artist

I’ve seen in person. More than anything, I expect her to once again write a

kind of manifesto—something like her earlier piece titled “Why Doesn’t Zara

Sell Masks?”—a 108th declaration mingled with anguish and resistance, starting

again from there. It sparks the notion that a manifesto worth writing today is

not about political agendas or social issues, but about “visibility.” The

belief that, because everything is visible, there must still be something

meaningful—soul, mind, essence—in the invisible realm is superfluous. Thought,

it seems, has vanished from online platforms. What once began in newspaper

opinion columns—individuals articulating their voices—has now filled every

blank space in the world with ads. Thought itself has become excessive,

unnecessary—philosophy, let’s say. Once that’s stripped away, what remains are

selfies and tutorials structured with narrative guides in online space. The

question then becomes: what kind of gesture or voice should be embedded in

these selfies? What’s needed is a specific “preset.”

Something to Consider

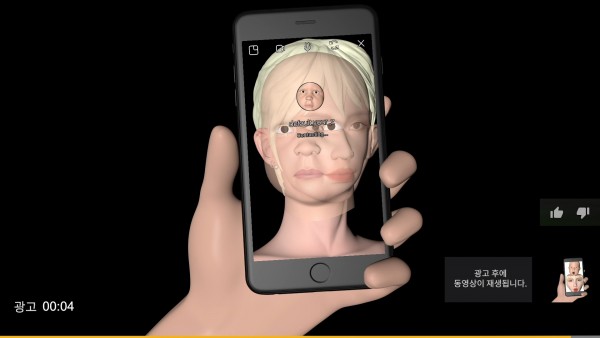

1. In Kim’s videos appears a future figure: Z, the Ooga Chaka

baby. But in reality, how many centimeters is the average fetus? From the

moment of birth, a baby grows. A human’s size in centimeters changes every

moment. There is an average—they say about 45 centimeters. A thick yellow book

titled The Birth of the Mother examines the scientific

process of how motherhood is formed. If you pay attention to one particular

plate containing an image of a primate, it shows how a baby animal,

specifically one that has lost access to its mother’s breast, gives up on

growing. The black-and-white photo shows an animal whose facial expression

seems to prove that this choice of resignation was made voluntarily. The baby

in Kim’s 《Default》 is neither old nor young. In its fragmented, digitized, unnatural

movement, the newborn is not a “baby” but a genetic composite. It is not a cute

baby figure designed to sell things, but a cultural artifact replaceable by a

number of chips. Meanwhile, during her presidency, Park Geun-hye once told

young people to “go abroad.” The K-MOVE project. Park, who initiated the K-MOVE

Project, essentially encouraged Korean youth to leave the country for jobs

abroad to such an extent that “Korea would be emptied out.” In a world where

digitality is the default dispersed setting, those born in the early to

mid-20th century are actually the newborns. And those who will be born in the

future are newborns with regard to the past. Amid the dematerialization of

overwhelming data possessed by each, material things may bid farewell to one

another—but the digital residues that accumulate and vanish instantly cannot be

dealt with. That Kim, through 《Default》, poses questions about who is to come is deeply significant.

Because people rarely afford time or space to think about others, Kim’s

hypothesis and occasional advice to unknown interlocutors may appear as

hard-edged black humor, but they are also a feminist voice projected by a

post-1990s artist toward the online screen. How can the internet be broken or

rebuilt? Where are the new materials to replace the yellow eggs hurled in

anger, the slogans from political films, or the choreographed dances of

protest? Because the enemy is not visible, the methodology of a baby’s first

steps in learning the world must await reconfiguration.

2. What could fill in the blank in the sentence “All that remains

is □□□” when written anew for each era? Walter Benjamin wrote about the decline

in the value of experience in his essay “The Storyteller and the Novelist.” He

reflected on how, compared to people of an era where “only the body remained,”

those who had lived through World War I and were bombarded every morning with

newspaper reports from around the world experienced a collapse in the value of

lived experience. Writing in the mid-1930s, Benjamin noted that previous

generations had only their bodies left, while his own era was flooded with

overwhelming information. “When someone goes on a journey, he has something to

tell.” “What arouses the readers’ interest most vividly is dry material.”

Hyojae Kim’s Theory of the Image

Dry material, and the idea that one has something to say after

going on a journey. For those who commit to online tours every minute and every

second today, “dry material” is a matter of sacrificing oneself and clumsily

channeling others. Hyojae Kim speaks directly to the screen, narrating the

story of the influencer “Kim Nara,” a new kind of human, and the image-product

that emerged from her—one that traveled through Harajuku in Japan and returned.

The story, like a boomerang, keeps coming back and plays in real time, never

concluding. For a generation that tells its own story as if it were someone

else’s, the issue of “how to manage the body” demands a new literacy for

decoding images. But no one is there to teach it. Learning, by all means, is a

good thing. Jean-Jacques Rousseau said that no human can become human without

learning. As Hyojae Kim has drawn out, as long as there is still a world to

learn about, the tools of speaking must take the form of a question. Perhaps

the artist is interested in the rhetoric of the world. Rather than fragments,

she is more drawn to the whole; more than her own interiority, she is invested

in a network of hearts.

Here lies the work 〈Do Mandolins Really Have a Physical Form?〉(2017),

and a short essay she wrote titled “Why Doesn’t Zara Sell Masks?” In the

former, Kim’s video shows her as an ambitious figure of a generation that

treats both video and online aggregates as mediums, or as one who casts a cold,

suspicious gaze at numerous beings suffering from boundary disorders—where the

border between offline reality and online fluidity is never 100% present.

Meanwhile, in “Why Doesn’t Zara Sell Masks?”, she addresses the aesthetic void

of Seoul. What plays a key role in this essay, I believe, is its title—and

perhaps the title is also its conclusion: in an age when fine dust and hate

were the most flapping issues of the 2010s, the mask emerges as a dual object.

A necessity for filtering pollutants, yet also a regurgitated object not purely

utilitarian. It does not merely cover the mouth—it can cloak one’s entire

material identity. In this sense, the mask becomes camouflage. Ultimately,

Hyojae Kim delves into urgent methodologies for existence in a world where the

invisible seems not to exist at all due to the frames of the visible. Why?

Really? These are not questions to find answers to. Kim’s questions aim to

observe and disturb the entire system. Rather than becoming a well-behaved,

clever player trapped in a fixed frame, she gazes at slightly foolish babies.

In this way, Kim is bolder—she doesn’t hesitate to jump offline from the center

of the online world. Her decoding and reading practice is a broad gesture of

rescue, one that seeks to compose a shared world by perceiving and coexisting

with others of the contemporary era.

“Don’t hate the player, hate the game” –〈UNBOXING〉