An Eroded Past, A Sedimented Future

Not long ago, I came across news that the seed vault located in the Arctic had

been flooded due to an unusual heatwave. Meanwhile, in the Alps, as the eternal

snow melts, debris long buried within is beginning to surface. While climate

change has made it possible to discover legacies of the past, from a

preservation standpoint, it also presents another kind of threat. When

something that has long been frozen in glacial ice is suddenly exposed to

sunlight at room temperature, it deteriorates rapidly. Such unexpected

phenomena made me ponder what should be buried and what should be excavated,

or, in the event that all of human civilization were to be reset, which point

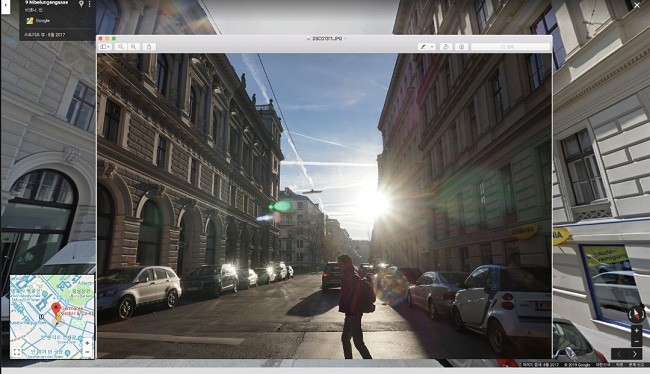

we should choose as the basis for recovery. Given that my attempt to visit the

World Archives in 2020 was canceled due to border closures, this felt like a

symbolic moment for me, prompting me to explore how one might respond to such

signs of change.

Amid

crises such as disasters, pandemics, and conflicts between nations, this

project begins with the question: “Can an uncertain future truly be compatible

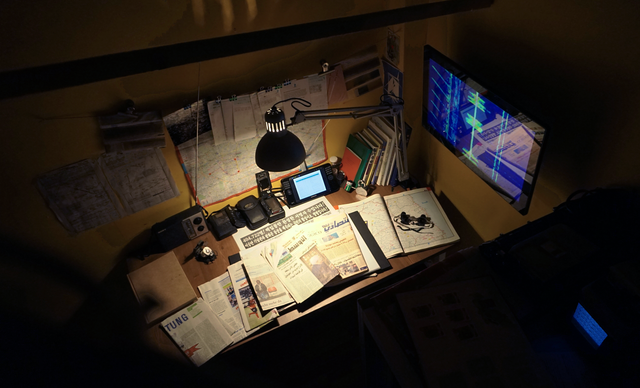

with the present?” To explore this, I looked into various preservation methods,

including visits to museum storage facilities and specimen rooms, and conducted

interviews with data managers, time capsule designers, and researchers of rare

book surrogates. From there, I identified three key preservation techniques

that reference existing forms and carried out procedures related to each.

The

first focuses on the boundary between an original and its duplicate created for

long-term storage, questioning the value of such surrogates. The second

involves observing how specimens or taxidermy works are prepared and stored,

presenting the surfaces in which the trajectories of objects are condensed. The

third examines the temporality of buried pasts and deferred futures, by

focusing on the procedures and forms encountered while observing time

capsule-related events. Perhaps, among these overlapping yet diverging backup

formats, we may be able to discover a valid clue to protect the records of the

present.

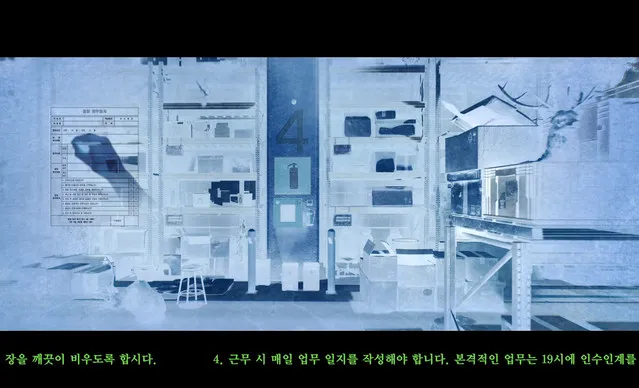

Where the World is Assembled, How We Leave Ourselves Behind

A cache refers to a temporary location or a hiding place where frequently used

data is copied. By storing data in a cache in advance, one can access it more

quickly without going through additional processes—thus avoiding the need to

recalculate values. Reflecting this functionality, selected objects were

rearranged in a virtual space. The site, set up like a film set, is filled with

multiple cameras filming different corners, while the arrangement of sets,

lights, and props is exposed just as it is—raw and unfiltered. This is a

deliberate exposure of the system behind the process of constructing a scene,

rather than showing only the final outcome.

Thin,

layered temporary walls suggest the operational logic behind the backdrop,

allowing for a vague inference. In this constructed archive-cum-film set, once

the cue is given, things that had remained still begin to vibrate. It re-enacts

a scripted scenario while revisiting relics that may one day be discovered and

prophecies that may one day be fulfilled. The elements casually arranged within

the space remain still, then move (as if alive), repeatedly switching between

states of pause and motion—tracing an invisible line somewhere between standby

and action.