Working as an independent

curator, she creates diverse exhibition programs and writes about art.

Additionally, she assists with public institutional agendas through corporate

and institutional consulting, outsourced research, and project planning.

Through her series of programs, she has maintained a consistent interest in

re-examining the formal characteristics and narrative methods that exhibition

media have preserved, as well as in altering/dismantling certain ingrained

aspects in the process of producing and arranging artworks. While supporting

artistic knowledge and aesthetic statements that resonate with the

specificities of contemporary art institutions, she maintains a slightly

critical mindset as she engages in dialogue with artists, examines the before

and after of exhibitions, and provides necessary responses and proposals.

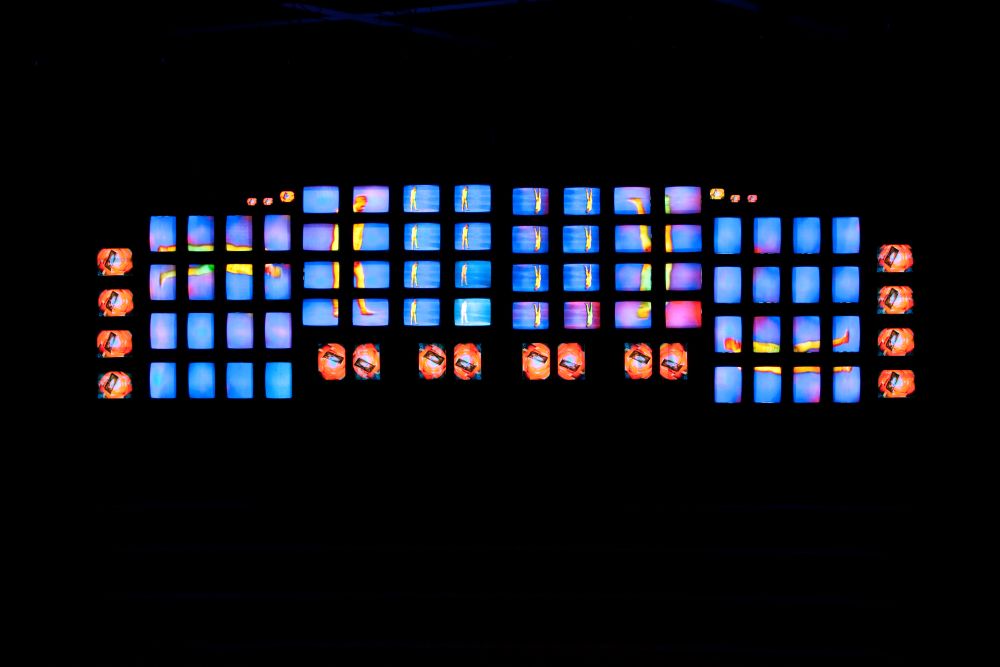

While Gijeong Goo employs the

universal approaches and special effects commonly used by today’s digital image

makers, it seems somewhat insensitive to discuss his work merely in terms of

effects or to broadly label it as media art. Depending on how they are arranged

and juxtaposed, Goo’s works function simultaneously as complete visual planes,

lower-level digital sources for something else, material masses embedding light

and sound, and products of experience design that shape the viewing body’s

radius. Despite the clear and explicit intentionality and self-articulation in

his works produced in recent years, Goo’s practice generates various questions

and implications about the production and reception of images. Goo’s point of

consideration appears to lie in increasing the complexity of relational

dimensions between technologymediated images and the body and the physical

world that encompasses the ecological environment.

The digitally transformed images

based on original photographs neither aim for realistic representation nor

converge into unreadable fiction. Though it may be a hastily coined term, if we

can apply the rhetoric of post to Goo’s series of images without particular

doubt, it doesn’t necessarily refer only to the productive aspects of digital

images related to manipulation and transformation. It’s a concept that

considers aspects of discrimination, division, and integration possessed by the

subject who senses the image. In this respect, if there’s something to be

gleaned from Goo’s work, it lies not in the uniqueness of the image production

process, but in how they actively imagined and designed the way it would be

received and read. It’s also worth noting with interest that this process is

based on sophisticated digital labor. Instead of acquiring cheap images

floating on the internet or purchasing stock images, Goo’s production method of

using ultrahigh-resolution macro camera shots and rendering them with professional

skill feels rather like intentional craft. While directing the computer

program’s interpolation and augmentation functions to create illusions of vivid

texture and depth as images transform from flat to threedimensional, from still

to moving images, they simultaneously maintain the contradiction of controlling

these results to prevent them from becoming typical images. According to the

artist’s shrewd intention, a small and subtle sense of foreignness seems

sufficient to widen the narrow gap between what is shown and what is seen.

Before a convincing spectacle, our task is to find these subtle gaps and fake

seams. We can either view the fragmentarily constructed screen as a

sewn-together whole or train ourselves in a mechanical viewing angle that can

appreciate it as is. We just need to remember that rendered images can be more

dramatic than reality. If we remember that the artist’s job is to intervene in

the countless processes of contraction and expansion that occur in transferring

images before our eyes, we can agree that the act of viewing is neither

autonomous nor active.

I gaze at the exposed

cross-section with multiple layers of vision. The series of landscapes created

by Goo appear natural and concrete while simultaneously being artificial and

ambiguous. Despite the remarkable verisimilitude that captures the retina, an

unsettling ambiguity remains about what one has just seen. The essence of this

feeling stems from slight crudeness nestled between seemingly smooth surfaces,

a discomfort emanating from nature that isn’t quite natural. If the artificial

sensibility that connects to nowhere in this world has been detected early on,

there must have been a subtle error in Goo’s calculations; if one felt nothing

strange until the end, they might be somewhat insensitive. Or else, we must

acknowledge the powerful fiction of images that have deeply permeated every

joint of the world we live in. In this regard, it’s necessary to examine the

various points of fiction and error surrounding the work from multiple angles.

This is not so much to cross-verify the arguments described through the work

thus far and the effects articulated through exhibitions, but because actively

discovering and intentionally integrating the minute gaps embedded in digital

images as a whole can enhance our resolution for viewing a world marked by the

entangled images.

Meanwhile, we can consider the

period around 2020 as the point when Goo’s work began to gain attention

domestically. Various experimental studies during his stay in Switzerland

appear to have expanded visibly in both quantity and scale during the COVID period.

Recalling how we encountered art and life in general through screens and

communicated through images during this time, we discover the advantages of

Goo’s working method. To simply understand his production method, he has been

creating variations by specially photographing existing natural landscapes,

digitally reconstructing and processing them, and presenting the results in

formats ranging from prints and videos to mixed installations. Looking at the

series of natural landscapes that has continued steadily each year from a

broader perspective, the individual works collectively form a world (Gye in

Korean) that repeatedly reveals the difference between our schematized visual

framework of the natural environment and reality. In modern society, where primitive

nature and civilized individual bodies coexist, it is digital augmentation

devices like cameras, prints, various projection equipment, and VR that most

intimately mediate this gap or, conversely, widen it. For Goo, who is

accustomed to working at a computer all day, the connectivity between his

working body and integrated devices, and conversely, the disconnection from the

environment, are conditions of daily life. As mentioned earlier, there was a

notable increase in image experiments and installation styles dealing with

nature and plants during the COVID period. This can be understood as an

auteurist trend of contemplating non-human existence through various natural

species and objects, naturally emerging based on interest in new materialism

alongside Anthropocene discourse. While it might be valid to some extent to

accept Goo’s work as an example corresponding to these contemporary trends, we

need to examine the issues in his work more pointedly. What’s important is not

so much the amazement at digital sensibilities deeply infiltrated into today’s

human body and sensory organs, but rather how we can operate to examine without

misinterpretation the image of the world that such sensibilities restructure,

interpolate blank points autonomously, and recognize integrated parts through

differentiation. It’s about being deceived by visual illusions, actively

accepting their obviousness at times, and partially filtering them.

The artist has consistently

posited scenes, landscape, realm, and nature as spatial modules in his work

titles, and by adding rhetoric such as Exceeded, Synthetic, and Macro before

them, he has directly reflected that these are both portraits of today’s nature

and the reality of matter. The notion that exceeded nature can only be depicted

through exceeded technology, and synthetic nature can only be shown through

synthesis, seems honest in one sense yet feels like a broken solution

somewhere. The cross-sections of soil and earth, the breathing holes of moss

and grass, and the vibrations of what appears to be microorganisms encountered

through the work converge into an unfriendliness due to excessive detail,

approaching as an excessive movement opposite to the vibrancy that life

emanates. And these aspects constitute Goo’s intended rendering method for how

they gaze at and wish to show the world.

However, countless artists have

dealt with the complex relata surrounding nature, humans, and technology

through various visual languages, and it remains one of the most crucial topics

in today’s socio-cultural discourse. Naturally, questions persist about where

Goo’s work stands in terms of its distinctiveness or uniqueness within this

context, and about the true nature of visuality that defines our lives today.

If there is an interim conclusion that the artist has reached through their

work by alternately connecting the axes of digital nature and digital (-ized)

body, analog nature and analog body, it seems to be stating that their

respective data and textures are interconnecting or overlapping somewhere in

reality; ultimately in an indistinguishable state. And reaching this

recognition has involved a kind of visual struggle. I’d like to call this

process a form of artistic rendering. Render, one of today’s readily accessible

terms, carries a comprehensive meaning of transforming something into another state.

For instance, it refers to a performer’s process of translating sheet music

into music, the technology of processing raw materials into different forms

(like solid to powder), and the process of integrating effects—shadows, colors,

textures, etc.—in editing files to create final video output. The world

rendered collectively by Goo, his camera, and his computer programs markedly

differs from reality, but let’s consider whether this is problematic—or perhaps

not—in today’s world where images are becoming increasingly more expansive than

reality. While directions of direction, depths of depth, and intensities of

intensity split and merge to create certain images within the artist’s

displayed screen, let’s remember that in the world outside the screen, objects

can be more distant than they appear, nature can be shallower than it sounds,

and people can be lighter than they feel. This is because the screen is not a

mirror image of the world. The final authority to disassemble and re-render the

unevenly rendered world’s layers can only be oneself. That will be each

person’s mirror and way of rendering to control the world.