Boxing has a noir-like

prehistory. Recalling the story of how shady, underground betting fights grew

in popularity before eventually being legalized, boxing without an opponent,

boxing outside the ring, seems to have lost some of its original power. In old

movies, comics, and pop songs, boxing was always framed by the narrative of a

climactic fight. In contrast, boxing as a choreographed dance—punches thrown in

the air, arms flailing—becomes a series of repetitive movements. The

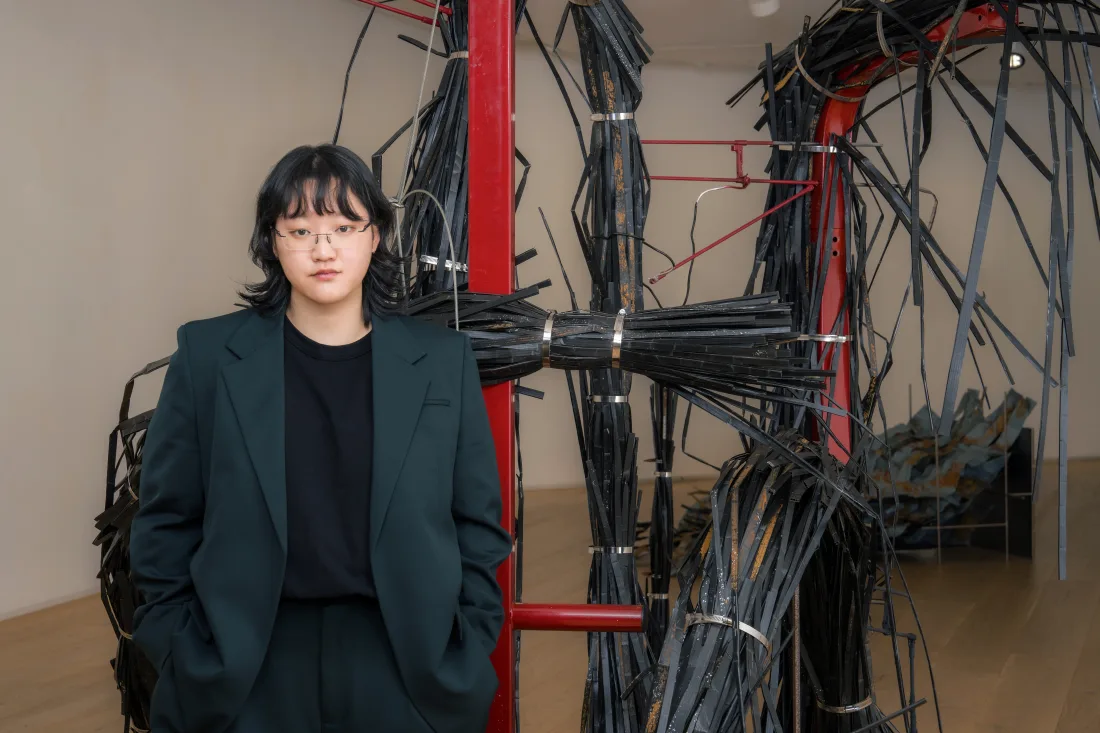

exhibition Boxing Sketch evokes this latter image

rather than the former. Through this exhibition, Eugene Jung reimagines boxing

as a gesture, embodying it in a sculptural (and theatrical) way.

Jung has been preoccupied with

contemporary issues surrounding disaster and image. Her representations, which

have been described as “ruin fantasies” (Hyo Gyoung Jeon), do not echo Western

aesthetic traditions that romanticize ruins as picturesque landscapes. Rather

than indulging in the comforting, familiar fiction of fantasy and its

domesticated community of taste—which inevitably appeals to the aesthetic

senses—Jung critiques the distorted present, where the image exceeds

representation. By referencing disasters framed as “memories of an

indeterminate future” (Yoon Wonhwa)—such as Chernobyl, Fukushima, and

others—she shifts focus to the present as something perpetual, rather than

consuming the future that creates anxiety of “We don’t know when it will happen

to us” or the past which allows for empathy.

It’s easy to say that disasters

are recurring. Similarly, it is all too simple to claim that images of disaster

are being shown too frequently, too intensely. It is devastatingly easy to look

at a vast mountainous collection of images and think of the lives swept away by

a tsunami or the heaps of ash left in the wake of war. Amidst this, Eugene Jung

reflects on the relationship between disaster and image, shifting focus away

from merely proving(attesting) or recreating the reality of disasters and tragedies.

In her work, the image itself

resonates with the status of disaster today. In other words, she juxtaposes

this with the notion of the “pirate” as the title of her work suggests.

Publicly circulating “pirate” reproductions are (1) “real” in the sense that

they bypass authentication processes—the demand for pirate copies arises from

their realness, not their fakeness—and (2) inherently simultaneous, as they

circulate widely and pervasively. These images, as everyday objects, overwhelm

us before we have the chance to assess or determine their authenticity.

The “boxing” at the forefront of

this exhibition plausibly parallels the artist’s approach. The artist, who

trains in the boxing gym a few times a week, does not spar or hit punching bags

but instead focuses on learning the forms and repeating the movements. Rarely

does she engage in actual competition in the ring. In this sense, when Jung

shapes her body, whether as a physical body or as a sculpture, it is not viewed

as a preliminary step toward something else. Just as her boxing practice is not

about preparing for a future victory through punches, the disaster-image in her

work is not defined by its reference to a specific subject or reproduction. The

image’s manifestation itself becomes the central focus, where time is neither

suspended nor accelerated, and the image, as a present state of motion, is what

demands attention.

However, Boxing

Sketch should take a step further than merely continuing the

trajectory of works like RUN (2022, Museumhead,

Seoul), which explores the sense of running through a world without exit,

or Pirated Future + Doomsday Garden (2019, Art

Sonje Center, Seoul), which blends theater and reality in an inverted cinéma

total. In this new work, the artist confronts the question of what or which

image to rescue. Boxing Sketch imagines a new

image, one that shifts away from the disaster-image that have permeated Jung’s

previous works. It represents an experimental prelude to her broader inquiry:

Can the “disaster- image” which currently defines the fabric of reality, be

replaced?

Boxing Sketch is,

above all, an exploration of “sculpture.” (It’s worth noting that the

sculptural quality of Jung’s work has become increasingly prominent in a series

of new works such as Earthmovers (2024).) At the

center of a boxing ring, Friends

(One-Two-Hook-Upper-Weaving-Long) (2024) presents a series of

sculptures made from ready-made objects and materials echoing the artist’s

earlier works. Each piece has a sculptural volume that references the human

body as a unit and is based on the movements of boxing: jab, cross, hook, and

uppercut. In essence, the objects in Friends embody the form of a person in

motion, performing a sequence of boxing movements. These “human sculptures”

function as independent sculptural units, even though they appear temporary and

hypothetical, with the artist deliberately giving the materials a worn, used

appearance.

If the viewer can effortlessly

imagine movements such as raising an arm from below to above or lifting and

extending the body, it is because the work traces the trajectory of movement

with a line. This is more clearly evident in Square Jungle (2024),

which unfolds a cartoonish scene of fists flying. The three subsequent pieces,

each featuring different drawings wrapped around punching bags (Cotton

Fist Punching Bag, Water Fist Punching Bag, Fire Fist Punching Bag (2024)),

also seem to create images using a similar methodology. Here, while each image

embodies the graphic flatness and linear sense of speed, it is important to

note that the sculptural volume of the works, approaching human scale,

emphasizes presence and spatiality.

In Boxing Sketch, the sculpture

evokes the space between the body and bodies, actively engaging the viewer in

that gap, taking on a theatrical quality. Through her two solo exhibitions in

Korea, as well as her other installations, Jung has been constructing certain

sceneries by positioning her works “in a potential and complex relation to the

‘act of exhibition'” (Hyukgue Kwon). Even setting aside the fact that she often

worked with relatively long-duration videos/films, the aspect of cultivating

the theatricality of the site and presence, rather than the internal

completeness of a single work and the resulting immersion in the present, can

be said to be a characteristic of Jung’s sculptures and the expanded nature of

her installations.

The exhibition drew both the

works and the audience into a highly specific environment: a boxing gym. In

this way, the theatricality of the sculpture, heightened by the setting,

naturally encourages the body of the viewer or gym-goer to engage with the work,

thereby activating the understanding of the entire scene. A viewer, who

approaches the exhibition and works both casually and aesthetically, must

interpret what is before them as a “collective body” (Hyukgue Kwon), while also

experiencing it as an intensely personal body.

The presence of theatricality,

which subverts presentness, offers a clue for transporting today’s

disaster/image to another (somewhat anachronistic) dimension. In a neighborhood

boxing ring, a training ground for daily life, the gestures of the artist and

amateur boxers—jumping, throwing punches—are incorporated into sculptures and

scenes. Without a narrative, can these images reclaim the sensory appeal it

inherently carries? What is needed is a sense of “recovery”—not in the sense of

restoring a past state or reviving the ruins, but in awakening to the presence

of the here and now. This perhaps foreshadows what comes after the

disaster-image.