Earlier this year, as the novel coronavirus spread worldwide, the

WHO(World Health Organization) declared a pandemic on March 12, and on March

25, the Japanese government and the International Olympic Committee agreed to

postpone the Tokyo Olympics. Around this time, a scene from the 1980s Japanese

animation Akira was circulating on the Internet with the saying that

it accurately predicted the future. It is a scene with a billboard

advertisement saying, “The 30th Tokyo Olympics. 147 days until the event. Let’s

make it a success” and graffiti that reads “Smash” and “Stop, stop!” below it.

Initially, Akira drew attention in that the setting of preparing for

the 2020 Olympics in the future Tokyo became reality, but by February 28, which

was 147 days before the actual Olympic event, its meaning was reversed as

predicting today’s situation which seemed impossible to hold the event

successfully. After the postponement of the Olympics was confirmed, this scene

was framed and propagated as not just ominous or disturbing, but as a

shockingly accurate prophecy.

Prophecy is different from prediction. For example, when a

Japanese artist interviewed by the artist Eugene Jung in her piece Pirated Future says,

“The Olympics are actually next year,” it is not strictly a prediction. Because

at that time, it was a known fact that the 2020 Tokyo Olympics would be held.

It was a decided future and the present was planned and executed accordingly.

That is why, at this point when that future is canceled, he does not sound like

he is simply saying a wrong prediction, but it sounds like he is speaking from

the other side of the time that is already slightly different from now. In a

slightly different sense from not being able to go back to the past, it is

impossible to go back to the time when the 2020 Tokyo Olympics were supposed to

be held. When the future changes, the present and the past also change

together. We live in predictions and plans that have not yet been realized but

that are regarded as confirmed facts. When scheduled events are canceled and

plans are repeatedly delayed, but even the minimal forecast required to plan

again becomes difficult, the present becomes as fragile as a sandcastle on the

beach when the future is unilaterally pushed in and out.

When the uncertainty of the future engulfs the present, prophecy

gains strength. Prophecy is more in line with planned predestination than

probabilistic prediction in that it clearly depicts the future. But a prophet

is not a planner, but merely a person strongly obsessed with a story or scene.

Such fiction can be seen as a ‘revelation’ of some almighty one who can

determine and realize the future, or it can be the ‘prayer’ of curses or

blessings as the intense and infectious aspiration of the most helpless without

such power. However, the so-called Akira prophecy was neither a

revelation nor a prayer. Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira depicts the

near-future Neo Tokyo preparing for the 2020 Olympics after World War III in

1988 which was caused by an unexplained explosion in Tokyo. Neo Tokyo is once

again destroyed by a flood of superpowers trained as war weapons. It was a

twisted projection of the time from World War II, which ended in Japan’s defeat

in 1945, to the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, which was the culmination of post-war

chaos and reconstruction plans. There is a memory of an indeterminate future

that is made possible by repeated history but not completely the same. It is

that dimension of the future that Pirated Future is attempting

to trigger and occupy.

Disaster in the form of shadows

Basically, Pirated Future is a

documentary film that intersects the Chernobyl nuclear power plant explosion in

1986 and the Fukushima nuclear power plant leak in 2011 from the present point

of view. In 2019, Japan was preparing for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics and the 2025

Osaka Expo as if equating the Fukushima accident with the atomic bombing in

1945 or at least trying to repeat the successful reconstruction of the postwar

ruins once again in the future. In response, the film proposes to reflect on

today’s time in Chernobyl rather than Japan in the 1960s or the catastrophic

sci-fi image of the 1980s. What does Chernobyl, the site of the most

representative and deadly nuclear accident, look like now more than 30 years

later?

Regardless of the cause of a disaster, the aesthetics of

reconstruction emphasizing its heroic overcoming, or the aesthetics of

catastrophe enjoying the possibility of extermination by it, both fetishize

power and mobilize images as monuments of such power. However, Chernobyl and

Fukushima, visited by the artist, remain in a slow and wide time that does not

revert to the spectacle of disaster. Remaining in those times does not mean it

is completely stalled. Everything on-camera moves and changes at its own pace. Invisible

radioactive substances, soil and building debris covering fields, thickly

overgrown grass and trees on top of them, and people living amidst these and

those who left them all meet face-to-face or connect from afar with their own

clocks moving at different speeds. The complex time formed by such networks is

not given in advance as a single total era but slowly emerges through a

mediating process, connecting the lines of different times as if knitting. The

film witnesses the pervasive shadow of the disaster, traversing Chernobyl and

Fukushima, but carefully examines the mottled traces of the shadow before

rushing to generalize it as a symptom of the era.

Risks are unevenly distributed. For example, even within

Chernobyl, the degree and color of danger felt differ amongst different groups:

residents who farm and live, refusing to move outside the restricted area;

local residents who develop relatively low radiation level area in the

restricted area as tourist destinations; tourists who visit to experience the

abnormal risk which they have only seen through the media; and experts who

demand countermeasures while informing people of the dangers of nuclear power

and the long-term effects of nuclear accidents. One could say that another

nuclear accident occurred in Fukushima because the Chernobyl accident has not

been properly explained, socially convincing, and thoroughly dealt with for

such a long time. (In this case, Chernobyl is the past of Fukushima.) However,

in the context of Japan, where the accident site of Fukushima is tied into a

no-entry zone to exclude it from society and seek a seamless reconstruction,

Chernobyl’s lively appearance can be read as a positive process in which the

accident area slowly recovers after a long period of isolation and reintegrates

as a part of society. (In this case, Chernobyl is the future of Fukushima.)

On the other hand, from the point of view of Seoul, where there is

no exposure to radiation, accepting the chain of disasters from Chernobyl to

Fukushima as images of reality that can be grasped, not as a one-time news

image or a disaster movie or game contents resembling it, in short, assuming

Chernobyl and Fukushima can be the future of Seoul becomes another issue.

Between disasters that have already arrived and the disasters that have not yet

arrived, explosive events that destroy a place, and the probabilistic death

that shortens people’s life expectancy, the dangers of the future stir the

present as undeterminable but impossible to overlook. Eugene Jung accepts the

air of today as a state in which shadow-formed disasters ominously blur the

vision, and the past and the future reflect each other indeterminately and

appear in the present like a mirage. In that air that cannot be easily shaken

off by hand, disasters sometimes seem to be very close and sometimes very far

away. The artist wants to point out that it exists there anyway and ask what it

looks like.

Living in Uncertainty

Pirated Future consists mainly of

videos and visual materials taken in Ukraine and Japan, and interviews with

locals involved in or embroiled in disasters in various forms. The film tries

to delicately show things that are not covered well or that are confined in a

certain frame with a specific meaning in the media dealing with Fukushima or

Chernobyl. However, rather than presenting it as real reality, it keeps

reminding itself that it is also in the chain of media images.

Films typically try to subtly show things that are not covered

well in the media dealing with Fukushima or Chernobyl or that are locked in a

frame of a particular meaning, but rather than presenting it as real reality,

they keep reminding themselves that they are in a chain of media images. The

meaning of the media image is not fixed in itself but flows with other images

surrounding it. For example, the scenery seen by tourists visiting Chernobyl

after encountering the game series ‘Stalker’, a game set in Chernobyl

developed by a Ukrainian company, is not natural in many ways. On the one hand,

the image and the actual scenery are imitating each other, and on the other

hand, the tourists themselves are looking at the actual scenery while

reflecting on the scenery on the screen. To accept the place as a reality, not

consuming the image of the reality as just a bizarre spectacle, but to

recognize it as a problem in the world to which one belongs, goes beyond simply

making an image well.

Rather than solving this problem, the artist left room for the

audience to realize it on their own and to some extent to make their own

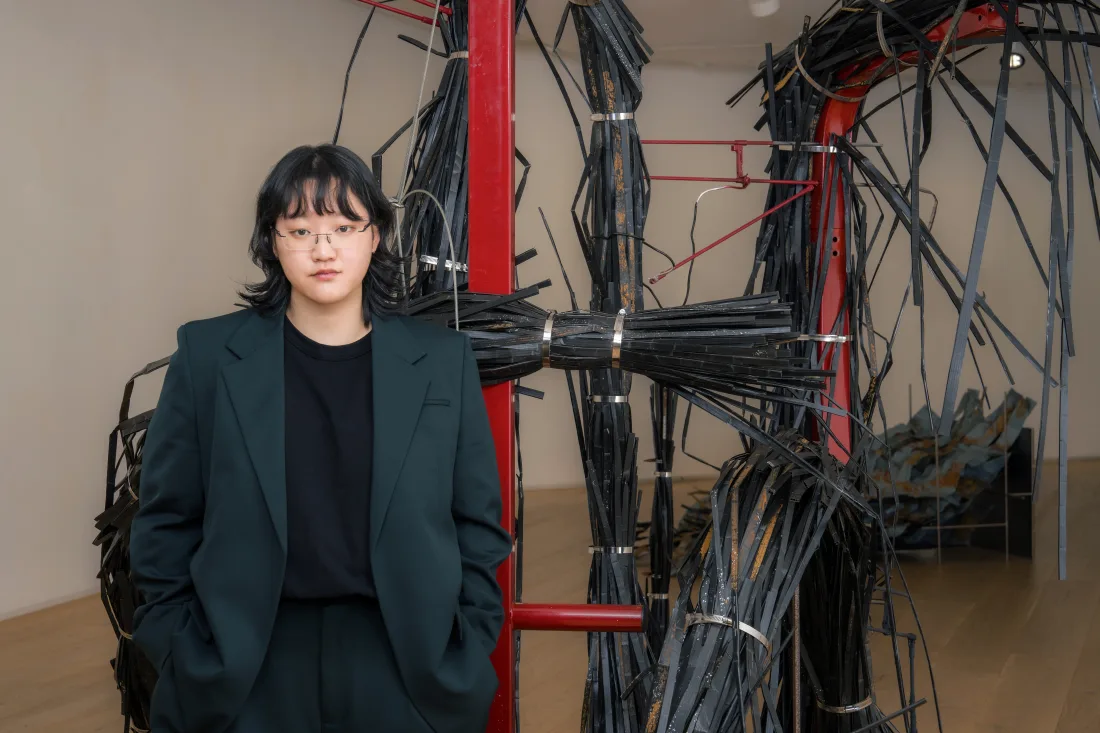

choices. Pirated Future was first screened

inside the installation work Doomsday Garden, which was

created like a movie theater after the extinction of mankind, covered with lush

artificial plants all over the stage and the seats. Who we are, when and where

we remain undecided as we watched the film together in a futuristic space where

if we say it’s fake, it seemed fake and if we say it’s real it seemed real.

This blank could lead the audience to a world of the post-apocalyptic genre but

could have also slipped into a space-time that would not be trapped in any

official narrative of Seoul in 2019. The shadow of disaster has sparked a new

terrain of time in which things contend: a series of timelines that consider

what has already happened to what has not yet happened as objective reality;

fragments of foreboding and memories that have not attained that degree of

certainty; and unexpected expression of non-visible things that have not even

been given such a hazy image. Pirated Future in Doomsday

Garden tried to amplify the sense of swimming through the opaque and

multifaceted flow.

At a time when film festivals and various festivals around the

world have been canceled and all screenings and conversations with artists have

been replaced by video streaming and remote conferences, the exhibition

landscape of Pirated Future + Doomsday Garden is

again dispersed into multiple layers of images that were unexpected at the

time. On the one hand, things that were difficult to get into the screen, above

all, the future of people’s bodies and spaces where they can gather together

became rapidly unclear. On the other hand, fighting the opaque and uncertain

has become an even more pressing and realistic issue. One might say that

maintaining an ambiguous attitude in art in such a situation where uncertainty

is already overflowing is either a tautology or an unnecessary surplus. But

when our own bodies were isolated individually as a place of danger and a place

of increased danger, all they could do was struggle with tentative words and

images that claimed their certainty more violently than ever before. In a world

where disasters in the form of shadows, which cannot simply be put as an end or

victory, unexpectedly come to the fore, Pirated Future exerts

a bizarre realism effect. It is not a “shocking prophecy of the future” and the

scenes in the film where people are gathered without masks already feel like a

bit of an unfamiliar past, but we are staying in a time that cannot be

confirmed.