“Carrier” refers to something that can hold or transport. It may

signify a pregnant woman, a vessel for transfer, a service worker, a

bloodstream, a container, or a mode of transportation. As a verb, “carry”

encompasses meanings such as “to be pregnant,” “to harbor disease,” “to conduct

liquid or electricity,” “to bear weight,” or “to attempt an idea.”

Mire Lee has been working with sculpture and installation using

simple mechanical systems and tactile materials. For Lee, whose sculptural

practice centers on the physical act of touching, the world is apprehended

through the most material clues. In this exhibition, she conceptualizes the

body itself as a “carrier”—a term that describes both the physical condition of

a human body and, perhaps, a larger conceptual framework that encompasses all

of her sculptures.

Lee’s “carriers” may be understood more concretely through the

concept of “vore,” a subcultural genre and shorthand for “vorarephilia”—a

fetishistic interest in devouring or being devoured whole. In a conceptual

sense, “vore” collapses the idea of distance by situating the subject inside

another body or drawing an external object inward. Taken to an extreme, this

fantasy conjures a return to the mother’s womb—a genderless, abstract state

evoking the primal conditions of human existence.

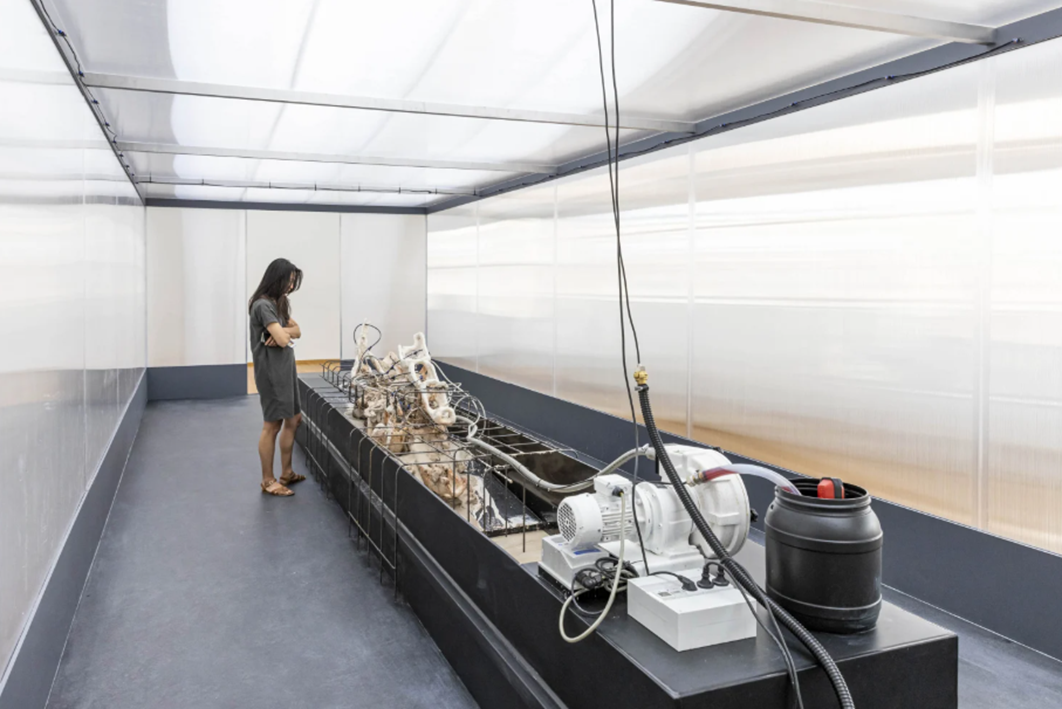

This notion is figuratively embodied in the titular installation

Carriers (2020), a new large-scale kinetic sculpture that

resembles an animal’s digestive system. Built with a hose pump mechanism, the

sculpture rhythmically sucks, transports, and expels mucous substances. The

viscous matter travels along the structure, accompanied by erratic sounds

generated by its movement—evoking the moment something living bursts through a

narrow cavity. For Lee, this energy is a sculptural extension of life itself.

Movement is not an accessory but essential; the machine is a motorized

extension of the material body she touches and activates.

In contrast, other sculptures in the exhibition adopt a markedly

different stance. Concrete Bench for Carriers (2020), a

cast-concrete sculpture, invites viewers to sit and observe the exhibition.

Works like Lying Forms (2020), situated low on the floor,

appear inert and passive, mirroring the quiet presence of the projected video

Sleeping Mother (2020). Among various bodily positions,

“lying down” requires the least energy. It is a state that, unlike death,

presupposes life—an open-ended and vulnerable condition. Lee draws attention to

this ambiguity: to lie still is to be susceptible, yet fundamentally alive. Her

dialectical juxtaposition of kinetic and static forms articulates the

ambivalence of human existence.

In some indigenous rituals, it is said that a shaman’s skin is

removed to heighten sensitivity and mediate the emotions of others. Skin, as

both a barrier and a receptor, mediates our perception of the world. Removing

this membrane collapses distance and minimizes misalignment between the self

and external stimuli. Lee draws inspiration from this tale to explore a

subversive potential: her sculptures, like skinless shamans, act as heightened

sensory agents—carriers that perceive the world on our behalf.

For Lee, sculpture is less about intellectual interpretation than

about physical and intuitive encounter. 《Carriers》 metonymically evokes the primal

movement of substances inside the body—blood, embryos, viruses,

nutrients—offering an experience where one becomes fused with the world through

the most intimate and corporeal dimensions of perception.