This exhibition stems from a continuation of the [No] series

presented at Gabeonkeugi at the end of last year. It began as a collaborative

process between artist Shin Min and a fellow woman curator, engaging in intense

conversations about both artistic production and exhibition-making, exchanging

energy as both comrades and creative partners. For Shin Min, making art is akin

to creating pieces of herself. As her body of work grew, we began discussing

the very real issues of storing and selling these works. Beyond the simple fact

that she had to take on outside jobs to pay the ₩2.4 million annual fee for

storage, I suggested that perhaps the artworks needed to be set free from her.

This led to the [No] project, in which we took the fragile clay

prototypes used to make her sculptures and distributed them to viewers—a risky,

deliberate act of surrender. The current exhibition follows in that spirit: as

the title ‘Flyer’ suggests, it began with the idea of distributing paper

handouts created by the artist, hoping that once dispersed, the individual

sheets would take on new meanings. As with [No], countless exchanges of “no”

occurred—two women with wildly different temperaments and instincts energized

and exhausted each other in cycles.

At that time, society witnessed a series of injustices. While

investigations into cases where women were victims showed little progress,

sensational media attention focused only on cases where women were identified

as perpetrators—such as a hidden camera incident. Massive protests broke out in

Daehakro, and the shocking Ahn Hee-jung case resulted in a not guilty verdict.

Against this backdrop, Shin Min began asking: Is there anything more powerful

than attending a protest? Could an artwork truly carry more impact than the

real-time voices echoing through social media? Confronted with the overwhelming

weight of helplessness, we were compelled to ask why, despite everything, Shin

Min continued to blister her hands working just to pour everything back into her

art.

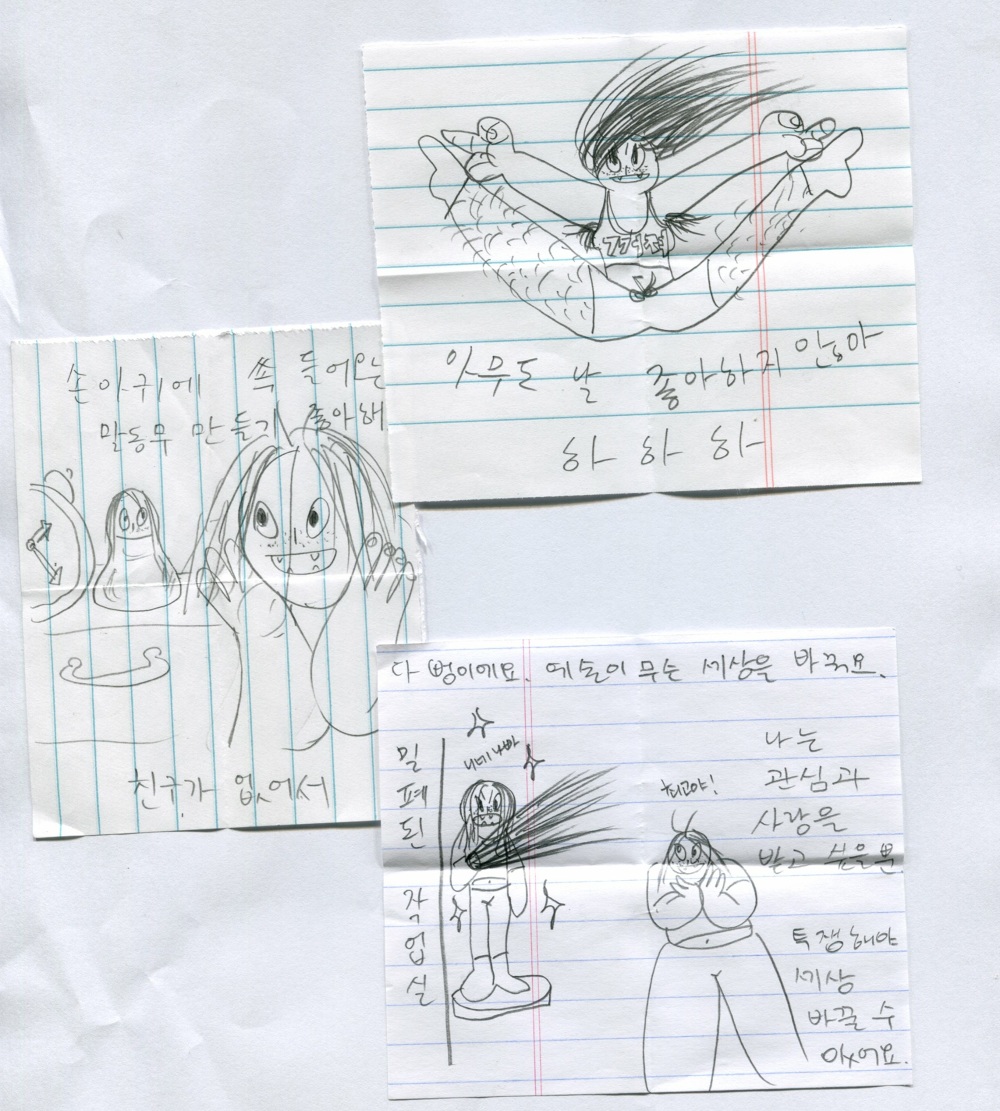

A ‘flyer’, by dictionary definition, is a piece of paper used for

propaganda, advertising, or agitation. Shin Min’s art, similarly, aims to

assert and persuade. Drawing on tiny sheets of paper or letters—often in the

form of doodles—and handing them out is her way of speaking to the world, of

starting conversations. In the gallery, she introduces these miniature versions

of herself, signs them, and meets people through her works. The exhilaration of

creating and handing out these intimate drawings gives her the courage to push

past her lingering insecurity about craft and dive back into art—an addictive

process akin to a drug.

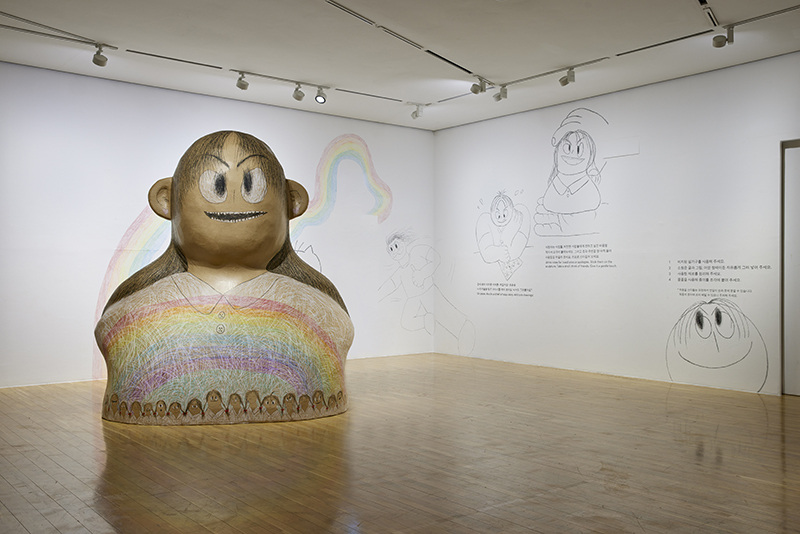

‘Flyer’ is a performance-style exhibition, centered on

distributing small sheets of paper made from delicate materials like notebook

paper and pencil. In fact, nearly all of Shin Min’s sculptures, large or small,

contain some form of paper scrap. Like the childhood belief that writing a wish

on a piece of paper and stuffing it into an empty pen would make the wish come

true, these flyers represent both a form of communication and a site of comfort

for the artist—a starting point for her practice.

In this exhibition, Shin Min cuts up common ruled notebook paper

and draws on them one by one with pencil, offering each drawing to viewers.

These flyers, fragile and easily smudged, could fade or disappear at any

moment. She has tried redrawing them on sturdier paper, switching to pen for

stability, or even considering mass production through printing. But the

combination that felt most true to her was the pencil-drawn flyer on ruled

notebook paper. Shin Min did not attend art school and was never academically

trained in sculpture or drawing. Thus, the standards and boundaries of

contemporary art have often felt especially rigid and inaccessible to her,

giving rise to her own artistic insecurities. By embracing the raw, unfinished,

even rough qualities in her work—and rejecting the polished perfection often

demanded by the art world—Shin finds her own way of overcoming these

insecurities.

The thousands of flyers she created may appear crude or unrefined,

but they reveal her care and sensitivity. The women drawn on these sheets defy

socially mandated standards of beauty and grooming. Harsh standards around

female appearance—present not only in the labor force but also in daily

life—perpetuate the idea that unadorned appearances signal a lack of discipline

or even diminished competence. Against this backdrop, Shin’s drawings depict

women with freckles, uneven teeth, and soft bulging flesh. In stark contrast to

the flawless women shown in the media, her characters proudly reveal armpit and

leg hair, shouting: “I don’t shave! I’m fine as I am!” Their awkwardness,

rendered with humor and charm, makes their defiance easier to embrace.

The quirky characters and scrawled, punchy messages written

alongside them create a strong resonance when paired with her modest

materials—pencil and paper. Through this, we catch a glimpse of Shin Min’s

unique form of resistance to societal scrutiny and judgment.

The ‘Flyer’ series, a kind of self-duplication practice, is

scattered throughout the books displayed at the front of the exhibition space.

These books include patriarchal literary works, essays, and poems we were

taught to admire in school—works whose values we were never encouraged to

question. They also include novels Shin once loved but later found betrayed by

the male-centered perspective she eventually came to recognize.

The sources of Shin Min’s anger remain as urgent as ever. In a

world where victims of sexual violence still often find no legal protection,

and perpetrators walk away without consequences despite media attention, it’s

easy for her artistic outcry to feel powerless. And yet, for her, the simple

act of handing out fragile, easily discarded flyers—objects that blend

seamlessly into everyday life—has become the most honest and powerful form of

protest she can offer right now.

Written and curated by Choi Ji-hye

Design by Matggalson

Supported by Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture