1. How to Read

“The word ‘derive’ scares those who believe politics must respect a set of

rules and that law must be the center of social life, those who think that

words have only one meaning, and that to understand one another in life it’s

necessary to use words according to their established meanings. This is all

wrong. When we speak, we don’t respect the meanings of words but invent

them….To understand is to follow the slides in the relations between signs and

referents…”1

The

above quote comes from Franco Berardi Bifo, an Italian Marxist scholar who

defined contemporary capitalism as “semio-capitalism” (capitalism of signs and

semiotic goods). This concept seems particularly apt today, when so much social

production and consumption involves financial derivatives or emotional labor,

while service industries frequently deal in subtle differences of signs. Such

practices are completely different from the industrial capitalism of the modern

age, which revolved around the production of material goods. In addition, Bifo

incisively points out that semio-capitalism has inverted the former autonomy of

signs, which were once used autonomously to invent forms of a new relationship,

but are now used to justify or even generate lies, swindles and scams. Bifo

used the word “derive” (to drift) to exemplify this inversion. For a while,

under the influence of postmodernism, “derive” had a positive connotation. But

under semio-capitalism, economic power routinely takes advantage of linguistics’

tendency to allow slippage between signs and referents in order to arbitrarily

manipulate the rules of politics and justice. Thus, “derive” has become

contaminated, and the contamination is spreading through the system like a

poison revealing the false politics and utter greed of economic power, which

operates above the law. As Bifo points out, the new interpretations of “derive”

are dislocated from the linguistic ideal of the invention of free, rich new

meanings. With the contemporary capitalist system, the deliberate invention of

meaning cannot compete with the rapid corruption of meaning or the mass

production of meaninglessness.

Bifo’s

critique of contemporary society, which cuts across politics, economics, and

humanities, can help to explicate the art of Yang Ah Ham in many ways, albeit

indirectly. These ideas provide an intellectual background and a useful

humanities and social sciences perspective for examining various aspects of

Ham’s art, especially Nonsense Factory, the project she has been

constantly developing since 2010, and which will be discussed in the final

section of this article. Furthermore, Bifo’s critique can also serve as the

foundation for interpreting Ham’s prevalent artistic themes in conjunction with

issues related to the transitory nature of social life, such as the freedom or

instability of relationality and the confusion of meanings or contamination of

values. Therefore, before starting the next section, I ask readers to take a

moment to again contemplate the ambivalent meaning of Bifo’s quotation.

2. Transition

Yang Ah Ham began her artistic career in the late 1990s, at a time when Korean

art, and indeed the entire Korean society, was swept up in the globalization

wave and thus moving towards greater diversity and plurality. She has since

become one of Korea’s most renowned artists, both domestically and

internationally, focusing primarily on video and installation works. Now, this

description may sound familiar, even cliched, to anyone who has read

contemporary art criticism. Exhibition catalogues, brochures, and bios

habitually tout the “international” status of the featured artists, usually as

a way of compressing information. Such phrases convey the impression that

artists deserve our attention simply because they have worked in various

places. But my brief summary of Ham’s career applies more directly to the

specific content of her art, rather than just the reception or scope of her

work. Although it may sound clichéd, Ham literally spent these years like a

nomad, living here and there, both “domestically and internationally.” This

lifestyle has been creatively crystallized in her works, which allow us to

simultaneously view opposing concepts, such as the interior and exterior of a

society, or the life of an individual and that of the masses. Of course, her

art is actually the cause of her “life in transit,” taking her back and forth

between antipodal aspects of life, such as familiar and unfamiliar spaces,

private and public spheres, and the visibility and invisibility of a society.

Ham

continuously observes contemporary social life, and her observations,

experiences, and contemplations inspire her to produce images of reality that

she then incorporates into her video and installation works. Her art

consistently focuses on the social reality where my life, your life, and our

lives are objectively revealed. With every work, her subjective contemplation

and her physical act of creation turn a spotlight on reality, critically

interpret it, and enact it into a different reality through the language of

video and installation media. But this “different reality” is not to imply that

her works depict a complete fiction or some innocent world of imagination.

Instead, her works aim to change our view and perception of the reality that we

typically ingest directly and unequivocally. Through her advanced artistic

capacity, she reconstructs this unequivocal reality by removing the

superficiality. For example, most of us are now well accustomed to life in the

era of globalization, and we automatically engage in daily activities such as

incessantly moving through virtual spaces via digital media, traveling across

vast distances of physical space via transportation vehicles, and toting our

belongings in suitcases through repeated departures and arrivals. Ham gathers

fragmented images of such activities in her video work Land, Home,

City (2006). By re-arranging real images into a “different reality,” she

evokes the essential aspects of contemporary life, which is marked by continual

flux, both online and offline.

The

primary impetus in Ham’s personal life and her art is the idea of “transition,”

which might refer to domestic and foreign spaces, a place to settle and a place

to pass through, different versions of reality, and the objective world and the

world as constructed according to an artist’s intention and execution. In all

of these dualities, the situation or movement of “transition” emerges. If we

are forced to remain fixated in one place and live one reality, and if we

cannot imagine any reality different from the one we know, then it is

impossible to conceive of “transition” as a “change into a different condition

or situation.” This helps to explain why globalism was so widely and rapidly

embraced in the 1990s, to the extent that it too became “globalized.” By

approving and promoting the cultures and values of diverse people, globalism

offered a way to overcome the homogeneity and obstruction of Western

imperialism and totalitarianism. As people everywhere eagerly embraced the

value of reciprocal exchanges and movements, globalism spread exponentially,

and contemporary artists played a key role in this trend. In actual terms,

artists contributed to globalization by participating in international

exhibitions and residency programs, but they further stimulated globalism and

transformed it into a social and political topic by producing

pseudo-ethnographic works that actively intervened in regional politics and

society.

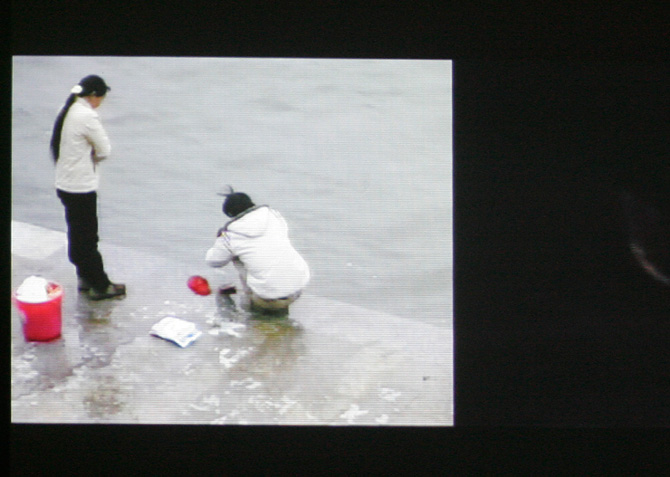

Ham’s

artwork from the early to mid-2000s exemplifies these aspects of

globalism. Illusion of Memory (2005) is a single-channel video based

on her research of small and medium-sized cities in China, which she conducted

while doing a residency program there. In Transit Life (2005), Ham

captures a nightscape of a ferry shuttling between Mokpo and Jeju Island,

representing our constant spatial movements, but also eliciting the unique

instability of the contemporary era. Dream in…Life (2004)

and Tourism in Communism (2005) revolve around similar tourist

carriages found in three different places (New York City, Chicago and Mt.

Geumgang). Although tourist carriages are an antiquated cultural form, they are

commonly appropriated by global tourism as an effective signifier. In these two

works, she forces the viewer to consider the differences between reality and

their dream of reality, as well as the political and capitalist ideology at

work in reality. These works represent Ham’s artistic responses to globalism,2 and

together they form a landscape of global-local transitions that she privately

captured in her “nomadic mode of life.”3 At the same time, they

provide opportunities to reconsider the meaning of the contemporaneous concept

of globalism.

3. Meaning and Non-meaning

For the last ten years or so, Yang Ah Ham’s artistic intentions and practices

have moved beyond simple visual collages that traverse oppositional aspects of

reality or hover between various social spaces and living landscapes. All of

the abovementioned video-installation works eschew a definitive, unitary

meaning in favor of neutrality and ambiguity that allow each viewer to form

their own interpretation. The scenes of these videos seem to be composed

according to the intermittent movements of various incidents, rather than the

expected narrative structure of an introduction, development, turn, and

conclusion. Furthermore, instead of directly proposing a message or moral, they

produce meaning through the multi-layered quality of the images, which

encourages the free derivation of meanings. We can infer that, at least at that

time, Ham’s works were more akin to an “image−mirror” that reflects reality, which

possibly extends its meaning in the process, rather than an “image−text” that criticizes reality or

provides further insights on society.

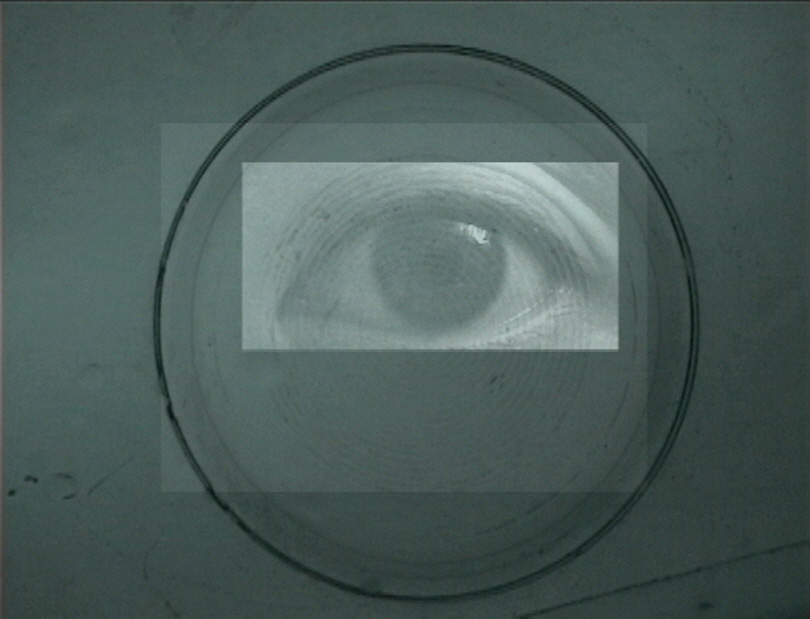

This

trend is exemplified by Adjective Life − Out of Frame, a

video-installation work based on performance that Ham introduced in Amsterdam

in 2007, which has since been featured at many major special exhibitions in

Korea and abroad. This work isolates the moments of our senses, perceptions,

desires, and appreciations, exploring how we relate to the things and people in

the world around us, physically or psychologically, directly or indirectly.

First, Ham sculpted a chocolate bust of a European curator who is well known in

the international art field, and then she hired five dancers to interact with

the chocolate bust on video. Rather than directing the dancers with specific

instructions or choreography, Ham gave them complete liberty to do anything

they wanted with the sculpture based on their own impulses. The resulting video

is a documentation of the flow of human will or desire, as the performers

indulge their impromptu whims to caress, lick, bite and embrace the bust,

simultaneously formulating both a physical relationship with the statue and a

symbolic relationship with the curator. We observe a wide range of interactions

between the performers and the sculpture, from subtle glances to sensuous

movements of hands or a tongue enraptured by the tender texture and sweet taste

of the chocolate. An interesting contrast emerges between the seemingly solid

chocolate and the living bodies that touch the head in a very primal and sexual

way. Furthermore, the behavior of the five dancers evolves throughout the video,

as they first circle around the unfamiliar statue somewhat apprehensively,

before gradually becoming more open and intimate with their gestures and

interactions.

Through this series of actions exhibits, we witness the

progression of feelings that a subject feels toward an object, demonstrating

that familiarity is not an abstract concept, but a parade of very detailed and

subtle senses. The viewers come to feel that they can unknowingly interfere

with and share in a range of different perceptions: the delicate interplay of

acts as people become entangled with one another; the progression between

feelings that are discerned by very minute differences; the exchange of keen

sensations. As such, the video provides a cross-section of the dynamics that go

into forming “social intimacy.” Adjective Life − Out of Frame visualizes how

our instinctual desires unfold and change in certain ways within the open space

of society or a community of coexistent people. For the audience, this work

serves as a communal stage where their own perceptions are interwoven with a

wide variety of sensations, including curiosity, eroticism, longing,

possessiveness, love, and hatred. All of these feelings and many more are

embodied by the dancers’ physical and emotional expressions with the chocolate

sculpture, the signifier of a person with some secular power. On this communal

stage, the audience’s perceptions add more layers to the complex system of

sensations that formulate our relationship with the world, such that the work

and the audience become entangled in another of the infinite relational

networks that constitute life.

The

title of the work is also worthy of interest, as Ham innovatively uses the word

“adjective” as an adjective to modify “life.” But the phrase also works like a

predicate, declaring that “life is an adjective.” Ham seems to view life from

the perspective of an adjective, rather than a noun, verb, or adverb, which

means that her art does not attempt to recreate or develop life as it is, but

instead acts to indirectly mediate and generate meaning, like an adjective. In

a positive context, this might be considered her way to “derive meanings.” Very

few people, if any, consider life to be a closed or complete system, but Ham’s

view of life as an adjective is still quite unique. As modifiers that can only

function by being attached to nouns, adjectives have a relatively unstable

linguistic status, since they can be replaced or nullified by other rhetoric.

As such, adjectives carry some implication of negation. But through her theme

of “adjective life,” Ham attempts to show that the essence of our lives (if there

is any) cannot be comprehensively surmised by a noun, verb, or adverb form.

Unlike nouns, verbs, and adverbs, Ham believes that adjectives are most

suitable to life, because adjectives can express the nature and condition of

life and, above all, existence. This perspective can be traced back to her own

somewhat transient lifestyle, and the unique values of that life that cannot be

deferred. Her oeuvre has emerged from her will to elevate that life into a work

of art.

Adjective

Life −

Out of Frame continued to evolve in 2010, when Ham created an entirely new

Korean version of the work. Audiences who encountered this updated version

experienced a completely different set of perceptions from those who saw the

original, again highlighting the “adjective” nature of our lives. Adjectives

are much more than innocent modifiers; they are capable of forming whole

expressions that are ineluctably deduced from the experiences and recognitions

that we accumulate, both socially and culturally. Indeed, certain social and

cultural conditions make it almost impossible to devise an adjective life. For

the 2010 work, Ham recruited ten Korean performers, who responded to the

chocolate head in a much different way than the performers in the 2007

Amsterdam performance. As opposed to the original performers, the Koreans’

interactions with the statue were rather peculiar, even a bit crude. At first,

they simply hang around the statue, making some curt, indifferent gestures.

Over time, however, they start to derisively snicker at the chocolate head, and

treat it explicitly as food to be eaten. Eventually, they stomp on the statue

to break it apart, as if seeking to vent their wrath against it. Viewers might

be reminded of an actor trying to maximize a certain emotion, but the more

subtle ways that the young Korean performers react and relate to the object

equally express their desires. Both form and content are crucial to determining

how we shape our lives, and in the case of the Korean performers, the unrefined

“verb” that spontaneously emerges is the content of the violent and rough

cultural background that serves as their form. Hence, their verb takes on

various rampant forms, as they “do” things without first probing the situation

with subtle perception; they “end” the relationship by “destroying” the Other

due to their inability to endure the delicate strain of their relations with

the Other; and they “exaggerate” their carefree attitude about the incident,

even though their actions are still swayed by their basic instincts. Thus,

interestingly, the 2010 version of Adjective Life − Out of Frame depicts a verb

life, or a life composed of actions that are somewhat absurd and nonsensical.

Thus, we must modify our earlier assessment that Ham’s art defined life as an

adjective by adding the following prerequisite: “not all lives are like an

adjective because of the structures of social consciousness and psychological

environments.” The 2010 Adjective Life − Out of Frame reveals the

possibility of a nonsense life, defined by the utter absence of meaning and

impossibility of self-awareness.

4. Derive ≠ Relation

If we are able to communicate about even the most subtle aspects of

sensibility, then we can achieve true freedom and beauty. Similarly, if the

meaning of a word is liberated to fully embody all the diverse possibilities of

perception, then we can achieve true empathy and communication between

ourselves and the Other. On the contrary, if the meaning is sterile or

stillborn without any variegation, due to our dull consciousness or violent

actions, then we willingly submit to the bridle that restrains us and forces us

to keep living in the same manner and mental state.

However,

there is a third possibility wherein rhetoric is corrupted, such that meaning

is supposedly liberated under the false guise of freedom. This leads to

embellished wordplay that inevitably devolves into lies and gibberish that

insinuate themselves into the legal, political, and economic discourse of a

society until the moral and ethical ideals have been completely subverted.

Bifo’s meditation on “derive” connotes such a case. Today, meaning has drifted

away amidst a flood of confusing new jargon: subprime mortgage, Free Trade

Agreement, derivatives, floating assets, Creative Economy. “Because of the

intrinsic inflationary (metaphoric) nature of language,”4 meaning

has drifted into a strange new realm where it can somehow be used to justify

the astronomical salaries of financial capitalists, to rationalize the unequal

trade conditions that multi-national companies thrive upon, and to enthrone the

chimerical concept of capital, based on numbers with no genuine assets behind

them, as the only value for us to revere. Is this negative development merely

an isolated case, among the almost infinite possibilities? Most people would

say no, because this rhetoric has been so loudly and consistently drummed into

our ears throughout the global network of the 2000s. Rather than an exception,

this phenomenon represents the cruel yet undeniable order of the reality that

we currently observe, and which we feel compelled to tacitly accept, either

voluntarily or involuntarily. In this reality, the “derive” of a meaning is

realized restrictively, in a way that is qualitatively different from the

freedom of relationship.

In

the past, we overcame oppression, uniformity, rigidity, obedience, closure, and

unilateralization with concepts like freedom, pluralism, fluidity, creation,

transition, and interaction, but today, the true value of these concepts has

been lost. Where has it gone? Simply put, those words are now adrift in a

purgatory between meaning and nonmeaning, such that their inherent value is

getting increasingly contaminated. Through Nonsense Factory, which took

her more than four years to produce, Ham offers a compelling artistic

consideration of this confusion of contemporaneous meaning, with particular

focus on how our values have become polluted to the point where we can no

longer hope to grasp their identity.

5. Nonsense, Factory

Adjective Life − Out of Frame represents a turning point in Ham’s career,

dividing the work that came before it from the work that came after it. In

terms of form and style, her work after Adjective Life − Out of Frame incorporates

various genres and media—video, painting, sculpture, performance, text and

audio—combined into a single work or project. While she did make video

installations prior to Adjective Life − Out of Frame, the earlier works

are primarily limited to the single-channel video format, while her works after

2007 utilized video in more complex, pluralistic ways. Notably, these formal

changes can be seen as reflections of the deeper cognitive and internal changes

that Ham was experiencing, as she matured as an artist and began to examine

contemporary life and society from a more critical perspective. As such, her

work always conveys a slight sense of aesthetic ambiguity, refusing to simply

settle into a neutral zone of a meaning. Her intentions for the work

are always very legible and communicable, allowing viewers to perceive and

judge it in a more detailed way. After Adjective Life − Out of Frame, Ham shifted her

priorities away from merely trying to cultivate artistic appreciation. That is,

rather than working within the typical relationship between artist and viewer,

wherein one of the two parties is always absent, she began exploring ways to

enact a much richer, more intimate relationship between artist and viewer. The

allegorical social critique of Nonsense Factory serves as a common

ground, allowing Ham to probe both the structure of our lives and their

internal dynamic function.

Nonsense

Factory started out as an allegorical short story that Ham wrote. For her

2010 solo exhibition at Artsonje Center, she printed the story in a large font

on contact paper, and stuck it to the glass front of the second floor of the

exhibition. Thus, rather than representing one of the visual elements of the

exhibition, it functioned more like a description that the viewer had the

option of reading. She also printed the story on regular paper so that viewers

could pick up a copy and read it. So what did she expect the audience to gain

from this story? In the current plans for the 2013 version of the project, she

explicitly identifies the “nonsense factory” with society. Hence, it is fair to

say that the meaning of Nonsense Factory is the meaninglessness of

contemporary society.

Nonsense

Factory depicts a factory set in a fictional location, adopting the

novelistic device of “coverage by a reporter for a company newsletter.” The

factory has six rooms: “Central Image Box Control Room;” “Welfare Policy Making

Room;” “Coupon Room;” “Artists’ Room;” “Factory Basement;” and “Blue Print Room

for Future Factory.” Those names—especially “control room” and “welfare

policy”—certainly ring true, as if they were culled directly from

reality. Nonsense Factory comes to resemble a microcosm of our

society, and those names are a big reason why. But beyond the titles, the rooms

themselves are eerily familiar to us, evoking various elements and functions of

our society.

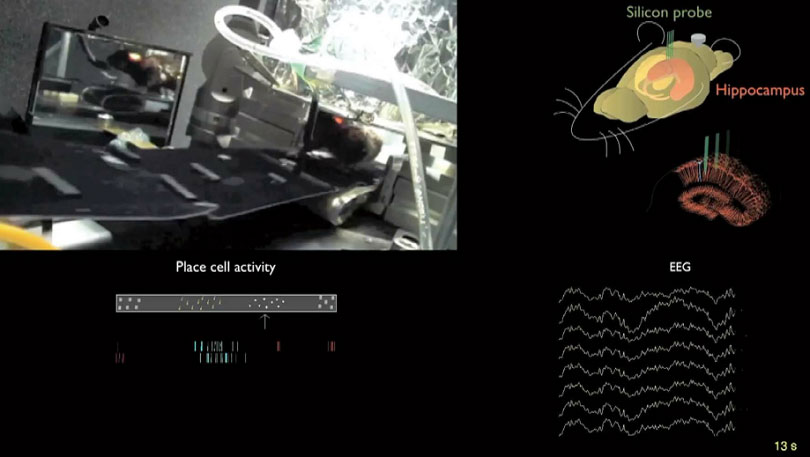

The

first room, “Central Image Box Control Room,” is both structurally and

functionally reminiscent of the ubiquitous surveillance and control of

contemporary society, where every detail of our lives is constantly recorded,

managed, and regulated under the omnipotent umbrella of cutting-edge digital

technology. Over the last decade, one of the prime topics for debate around the

world has been the increasing amount of surveillance and data-tracking enabled

by digital and video technology. In the years leading up to Ham’s creation

of Nonsense Factory, discussions on the dangers of such social controls

were becoming increasingly fervent, with more and more people referencing “Big

Brother” from George Orwell’s 1984 (published in 1949). Today, in 2013, as Ham

presents an even more highly developed version of Nonsense Factory, the ominous

predictions made by social critics have become a frightening reality that goes

beyond even Orwell’s fiction. In June 2013, Edward Snowden, a computer engineer

and a former employee of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), revealed

to The Guardian that the United States National Security Agency (NSA)

had been using computer technology to monitor and collect a wealth of

information from around the world. Specifically, the NSA used a computer

surveillance program called PRISM to monitor Internet users, including American

citizens, while also hacking into other countries’ computer networks to steal

confidential information. These types of activities are happening constantly

around the world, even though the majority of the population is blissfully

unaware of it. In Nonsense Factory, Ham uses the allegorical device of “Central

Image Box Control Room” to expose how the people of the world remain oblivious

to the state of surveillance.

In

the second room, “Welfare Policy Making Room,” a young factory employee is

buried by an overwhelming workload, such that he cannot take time to even lift

his head and catch his breath. The worker’s exhausting plight is contrasted by

the displayed slogan “Happiness for Everyone!,” recalling a pencil drawing that

Ham made and displayed in the entrance of Artsonje Center for her solo

exhibition in 2010, which was entitled I Came for Happiness/Submission.

Here, “I” might refer to the artist, but it could also be anyone who reads the

sentence. The overwhelmed employee might be a portrait of “I,” or it might be

the portrait of all of us who senselessly (non-sense) “surrender” to the empty

promise of “happiness” ideologically propagated by power. It might be a

portrait of Snowden before he became aware of the grave absurdity of his

society, and realized that he had to blow the whistle against his own country’s

illegal surveillance of people under the guise of world peace and security.5

In

the third room, “Coupon Room,” Ham satirizes the monetary economy of

capitalism, an analogy that is even more evident in the short story upon which

the piece is based. In physical terms, the coupons are simply pieces of paper,

but in reality, they are precious materials that make everything else seem

irrelevant. In her story, the managers and workers of the Nonsense

Factory use the coupons to accumulate wealth and gamble, while taking

advantage of the people’s psychological need for the coupons to lead them

around by the nose. The most significant room in Nonsense Factory is

the fourth room, “Artists’ Room,” which is occupied by a master artist who acts

very inhumane towards his assistants and anyone he feels is inessential to his

work. However, the artist spuriously tells the reporter of the company

newsletter that the most important attitude for an artist is the “understanding

of others.” Of course, hearing such a response from someone who treats people

so carelessly symbolizes the absurd snobbishness of some people, particularly

within the art world. But from a more macroscopic perspective, Ham’s explicit

reference to art based on the “understanding of others” illustrates a deeper

contradiction within the themes of artists. She is criticizing the structure of

public discourse, and its rhetorical deceptions, for reducing huge and complex

issues into themes for popular culture or talking points for political

elections. The “Artists’ Room” reflects the duplicity of artists and others who

latch onto trendy themes (e.g. “human rights,” “consideration,” “relationship,”

“communication,” “healing”) and appropriate them for their own use. This

duplicity that superficially addresses genuine social problems only serve to

confuse and conceal the real causes and effects of those issues, inevitably

paving the way for more economic inequality, manipulation, violence, imbalance,

non-communication and fragmentary relationships.

Thus

far, using a fictional factory as a stage, Ham has tried to reveal the

underlying structure and hidden attributes of contemporary life, as well as the

systematic relationship between people and society. But where is she going with

this endeavor? Perhaps she simply wants the audience to share her awareness of

the problem, and therefore recognize the serious forms of oppression and

restriction that are concealed by acclamatory names such as “Free Trade” and

“Creative Economy.” If the lives of the people are dictated by the will of the

system and the capital of those in power, then that is not freedom; it is

fascism. And it will remain fascism, despite the disguise of specious issues

such as flexibility, pluralism, horizontal exchange, networks of human and

material resources, as well as the supposedly rich meanings that are invented

and attached to such issues.

Nonsense

Factory concludes with the sixth room, “Blue Print Room for Future

Factory” where a “promising architect” is tucked away, covertly re-designing

the structure of the factory in order to create a “system to maximize

productivity.” When Ham developed Nonsense Factory into a full-scale

installation work in 2013, the first space was called “Factory Basement,” where

a group of anonymous people bumped into one another and energetically mingled

on a big platform shaped like a halfmoon or a ship. Due to the shape of the

platform, the motion of the people caused it to rock back and forth like a

cradle or seesaw. “Factory Basement” and “Blue Print Room for Future Factory”

seem to mark the beginning and end of the Nonsense Factory, allowing us to

tacitly recognize the two-faced nature of the society, as Ham intended. For

here we have an intensive system that purports to maximize productivity

connected to a structure of constant disturbance. The clandestine nature of

planning and policy-making is contrasted with the openness and visibility of

dynamic actions. I do not believe that Ham intended Nonsense

Factory to be a direct analogy of our actual society, but more of an

initial response or a warning sign. It seems unlikely that viewers who see the

moving platform and video of people mingling will suddenly start to imagine

freedom and a more intimate social relationship. But more importantly, visitors

to the Nonsense Factory might take time to reconsider our strange contemporary

times, when the lives of people around the world are dominated by instability,

and exchange and communication have become a global obsession.

1.

Franco Berardi Bifo, Gasry Genosko & Nicholas Thoburn (eds.), Arianna Bove,

Melinda Coope (trans.), After the Future (Edinburgh: AK Press, 2011),

105.

2.

For more detailed discussion of these works, see Kang Sumi, Wonderful

Reality of Korean Art (Seoul: Hyunsilbook, 2009), 164 -175.

3.

Reader’s Note: hereafter, direct quotations without reference come from Ham’s

own notes.

4.

Bifo, Ibid., 100.

5.

Snowden’s interview at The Guardian:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2013/jun/09/nsa-whistleblower-edward-snowden-why