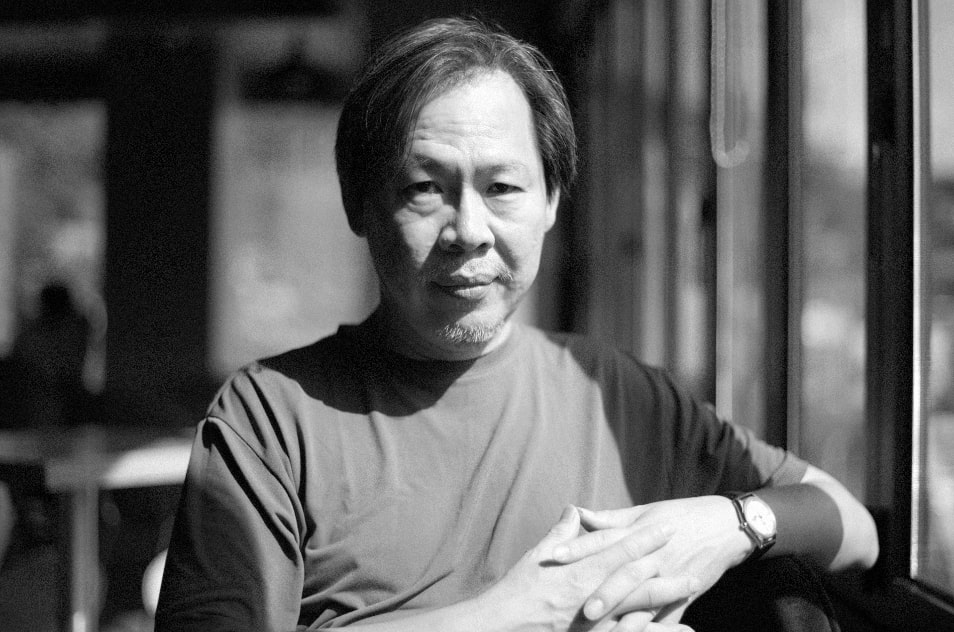

Park

Chan-kyong’s exhibition, composed of a 45-minute video as the centerpiece,

along with still photographs, architectural models, and a reconstruction of

archival materials that serve as explanatory supplements to the figures and

locations appearing in the video, is a genealogical inquiry into Mount Gyeryong

and the region of Sindoan located within it—places that one day delivered a

shock to the artist himself. The reason this work cannot be considered a

strictly empirical or historical documentary is because the tangible cultural

entity it explores, which until recently had survived as a living tradition,

has been largely lost due to neglect and distortion.

The

work analyzes materials related to Sindoan that were collected, classified, and

preserved by various groups holding either affirmative or critical views of the

place. It intertextually edits those sources together with footage and

interviews that Park filmed on-site to reconstruct a lost culture. The newly

woven text of “Sindoan” is thus tightly entangled with both empirical

historical records and mythological and religious imagination, to the point

where the two are inseparable.

Said

to have geomantic significance so powerful that Yi Seong-gye, the founder of

the Joseon Dynasty, once considered it for the new capital, the location is

today part of Gyeryong-si, Chungcheongnam-do. The name “Sindoan” has since

disappeared—its erasure implying the disappearance of the entity itself. The

Sindoan invoked by the artwork oscillates between past and present, imagination

and reality, revealing a hidden dimension of its existence.

Even

today, Mount Gyeryong retains a lingering association with hermits, recluses,

mystics, and eccentrics. According to Park’s research, the region had long been

considered a center for ideal society as imagined by geomantic prophecy

theories, ethnic religions, and new religious movements. Since the Japanese

colonial era, it had become home to hundreds of religious groups. Rather than

focusing on the superstitious irrationality and absurdity often associated with

such folk religions, the work concentrates on exposing the religious

unconscious of the lower classes—those marginalized and repressed throughout

Korea’s tumultuous modern and contemporary history.

The

Sindoan presented in the work is shown to have been persecuted and destroyed by

dominant cultural powers—first during the feudal era, then under Japanese

colonial rule, and later by foreign-backed authoritarian regimes. Yet it was

also a place where those driven out of mainstream society, whether voluntarily

or not, found refuge and renewal. Scenes of forced demolition under the

pretense of “purification” during the military dictatorships of the 1970s and

1980s dramatically illustrate how Sindoan was cast into the role of scapegoat

necessary to uphold the existing order.

The

so-called “purification” forces, appearing as if to drive out a deadly

epidemic, don armbands and Saemaeul Movement hats as they proceed to demolish

homes and religious sites. Compared to the obsessive and meticulous attention

paid by Japanese investigators who had recognized the cultural value of

Sindoan, this violence appears ignorant and barbaric. Nonetheless, even such

negatively biased documentation becomes crucial reference material in

reconstructing the place’s historical reality.

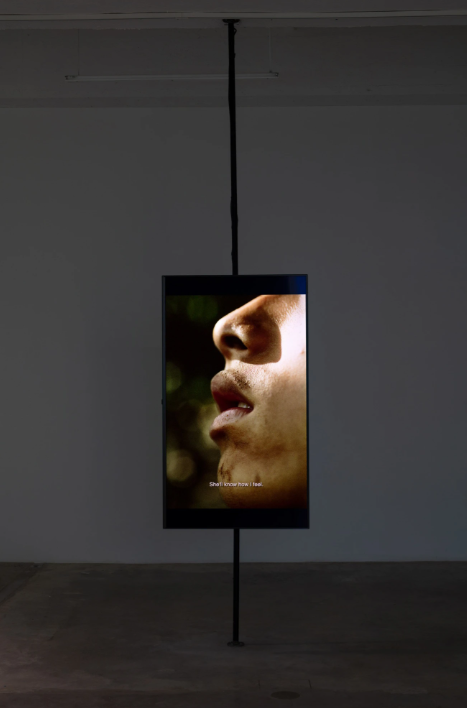

The

video is composed of six independent yet interlinked thematic segments. The

background music, with its repetitive rhythm, exerts a strong immersive effect

and tugs at the viewer’s nerves. The introduction begins with a dense cluster

of signboards for religious facilities situated beneath a large tree in Mount

Gyeryong. Faint black-and-white archival photographs are interspersed with

brief captions and interviews provided by the artist, while the camera’s

zoom-in and zoom-out techniques form a visual narrative. Past and present,

black-and-white and color, still images and video footage are seamlessly

interwoven—allowing the previously silent materials to finally speak. Fragments

of data, created in various times and spaces, are absorbed into the narrative

structure of the video, allowing a topic that is both old and new to be

reimagined for modern audiences familiar with moving images. As Park Chan-kyong

stated in a newspaper interview, his exploration of the religious unconscious

of the lower classes connects with the themes of “mutual life-giving”

(sangsaeng) and “resolution of grudges” (haewon) found in Minjung Art.

The

first work, Three God Shrine (Samshindang),

depicts the story and daily life of a female practitioner who claims to have

received a revelation from a “heavenly maiden.” Her speech may sound erratic

and tangled within the internal logic of the doctrine she believes in, but the voice

with which she describes her bodily experience of spiritual energy entering her

is full of conviction. The religious experience of Kim Jeong-sim, the head of

the Samshindang, is an irruption of the Other that tears apart the boundary of

ego identity. It is at once violent and mystical, terrifying and euphoric, and

carries strong contagion.

The

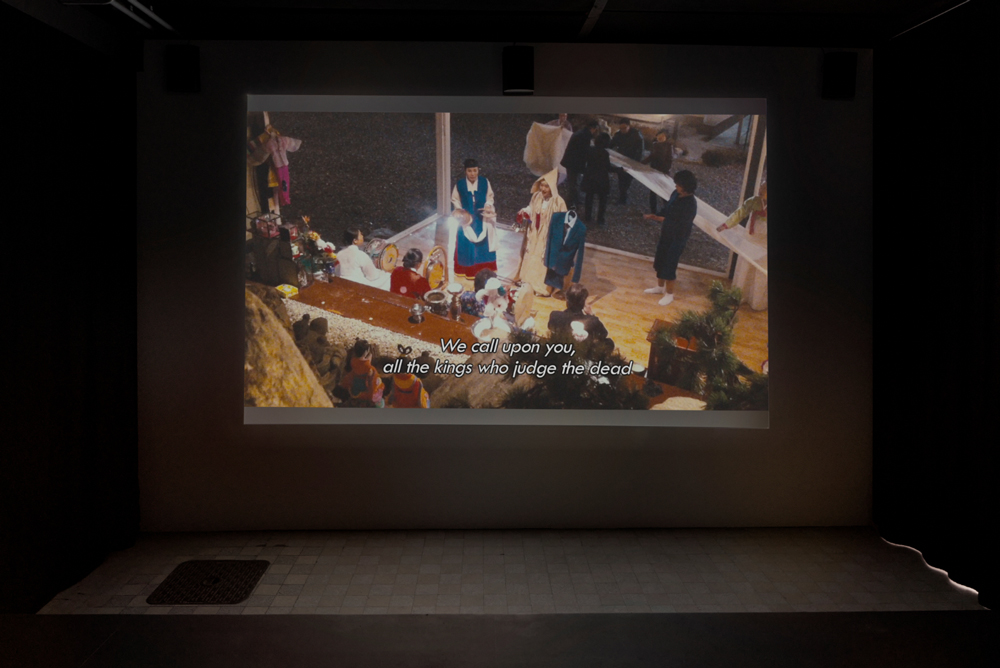

second work, Ritual Dance for the Departed (Yeonggamudo),

features performers demonstrating ancient chants and movements in a shabby room

with an old mother-of-pearl wardrobe. The camera captures without adornment the

earnest expressions of ritual dance practitioners Song Soon-gi and Na Sang-hyun,

who are entirely immersed in the sound and movement. These figures are not

merely objectified as exotic subjects—they represent the universal condition of

human beings, who are, by virtue of their mortality and limitations, inherently

religious.

The

third work, Commemorative Photograph, uses group

portraits of religious communities in Sindoan taken between 1924 and 1975.

Groups in bizarre uniforms stand out. What is surprising is not only the

diversity of religions represented but also the sheer number of their

followers—this is where the documentary character of the piece is most

powerfully revealed. It informs us that even at the time of demolition by the

military regime in 1983, 5,400 religious followers still remained. The culture

they had built was erased in the name of “environmental cleanup” and replaced

with new military facilities.

In

this segment, the hazy black-and-white archival photos are abruptly replaced

with vivid computer graphics and jarring English narration. This mirrors the

inclusion of Japanese dialogue in archival footage from the colonial era. Over

time, society has become more rationalized and systematized, but also more

destructive and aggressive. Among the works in the exhibition, the

juxtaposition of a traditional folk painting of a tiger and a tiger hunter in a

Western suit powerfully underscores this point.

The

work introduces numerous examples of folk beliefs that suffered under Korean

modernism’s alliance with foreign powers. Yet it paradoxically reveals that the

newly constructed octagonal military facility—built upon the ruins of

indigenous culture—was also not divorced from religious origins. If the

mechanism of creating scapegoats to reinforce the dominant order is itself the

origin of religion and society, then the conflict between religion and science,

or tradition and modernity, is not one of fundamental opposition but rather a

lateral transition from one religion to another.

If

we accept that beliefs which are now held by a few can later be held by the

many—and vice versa—then shedding light on the religious unconscious of the

lower classes, long excluded from modern and dominant cultures, carries

profound significance. Scenes from the old film Mount Gyeryong are

inserted, showing a self-proclaimed messianic leader and a crowd of

torch-bearing worshipers, creating the sensation of watching a film within a

film. There is no clear boundary between reality and imagination here. While

this is an effective method for examining a subject from multiple angles within

limited conditions, more fundamentally, it reveals that reality itself is a

product of human belief and will. This tendency is reflected most clearly in

the lives of the ascetics portrayed in the video—individuals who live entirely

within their own symbolic worlds.

The

fourth piece, Serving the Indwelling Lord (Si-cheon-ju),

features a practitioner of the Donghak-derived Si-cheon-gyo religion, which

existed from 1924 to 1983. The video transitions from black-and-white archival

photos to the present, showing a neatly dressed man in a suit standing alone in

an empty room. Moon Gyeong-jang, the leader of Seongdogyo, explains at length

the meaning of Si-cheon-ju (“the Indwelling Lord of all creation”), saying “All

things in the universe are Si-cheon-ju.” Though his discourse is lengthy, the

speech is delivered to no one, on a formal stage—symbolizing the current state

of his religion.

As

he chants the name of Si-cheon-ju in intonation, sits cross-legged, and writes,

his monologue continues. Most of what he says consists of religious doctrines,

but when scenes from his mundane present-day life appear, a sense of

incongruity emerges.

The

fifth piece, Kuvera, is a “believe-it-or-not” tale

linking Kuvera, the Sri Lankan god of wealth, and the claim that Buddha’s true

relics (jinsinsari) were transferred to Mount Gyeryong. An Indian woman,

mysterious and exotic in atmosphere, appears. Scenes follow in which characters

from earlier works gaze up at a celestial energy shooting across the sky like a

comet and landing in Mount Gyeryong.

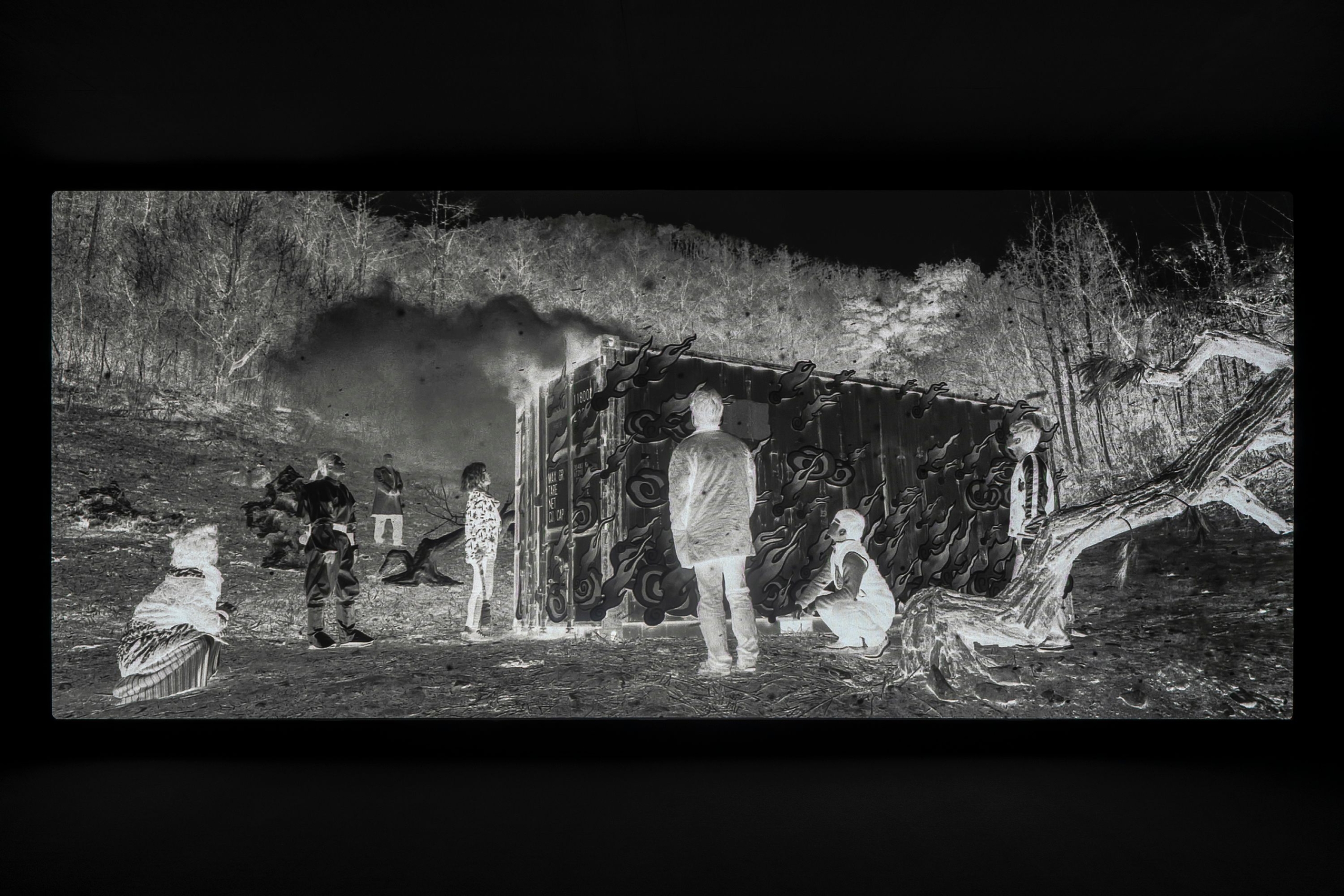

Lastly, Yeoncheon

Peak, Mount Gyeryong tells of a story in which young people who

survive an apocalyptic future gather at Mount Gyeryong. As the six episodes

unfold, fictional elements become increasingly prominent. A young man dressed

in a tiger costume takes the place of a divine tiger guardian; a scuba diver

emerges from a great flood that hastened the end; a girl in a fluttering dress,

oddly out of place on the rugged mountain; a figure in a school military

uniform with a black plastic bag over their head; and surreal, bodiless clothes

that move on their own—all come together on Yeoncheon Peak to perform a strange

ritual while holding hands.

The

work proceeds with solemnity only to end somewhat absurdly. But isn’t this

duality itself a trait of religion? The fundamentalism of religion plays the

role of the Other, reflecting back upon a modern society consumed by hollow

uniformity. The characters portrayed are, on one hand, marginalized figures;

yet on the other, they are transcendent and sacred beings.

Historically,

the diverse folk religions centered around Mount Gyeryong—often scapegoated by

the ruling elite—have functioned both as conservative forces reinforcing the

established order and as mythic centers of resistance seeking to rupture that

order. The artist points out that Sindoan historically gained vitality whenever

Korean society fell into disorder. The folk religions of Mount Gyeryong, long

suppressed as heresies, resemble Western eschatologies that, though

marginalized in ordinary times, sometimes emerge to offer revolutionary

visions.

Throughout

history and across cultures, religion has served as a foundation more

fundamental than society, history, or art. Religiousness exists deep in our

unconscious precisely because we do not fully understand it—yet it exerts

persistent and decisive influence. Concepts such as reason, interest, and

social contract are merely surface phenomena resting lightly upon the vast

ocean of religious unconscious. Thus, the role of art may be to draw out a

moment of liberation—not from blind faith or regression, but from within the

very irrationality of religion itself.