At

the far right corner of the first-floor exhibition space stood a telex machine

on a pedestal covered in leopard print fabric. The telex had a slide tray and

deer antlers mounted on its head. It was clearly a metamorphosed telex. Then

what is the “body” of this transformed figure? After reaching the telex, the

audience could loop back and re-examine Small Art History,

proceed to the archive by the entrance, or walk behind the wall to view Citizen’s

Forest. Upon exiting Citizen’s Forest, one

again encounters the archive and can ascend to the second floor. On the second

floor, viewers encounter Bright Star, Chilseongdo, MoonWalk,

and finally The Way to Seunggasa in sequence.

Thoughts Stirred in the Heart

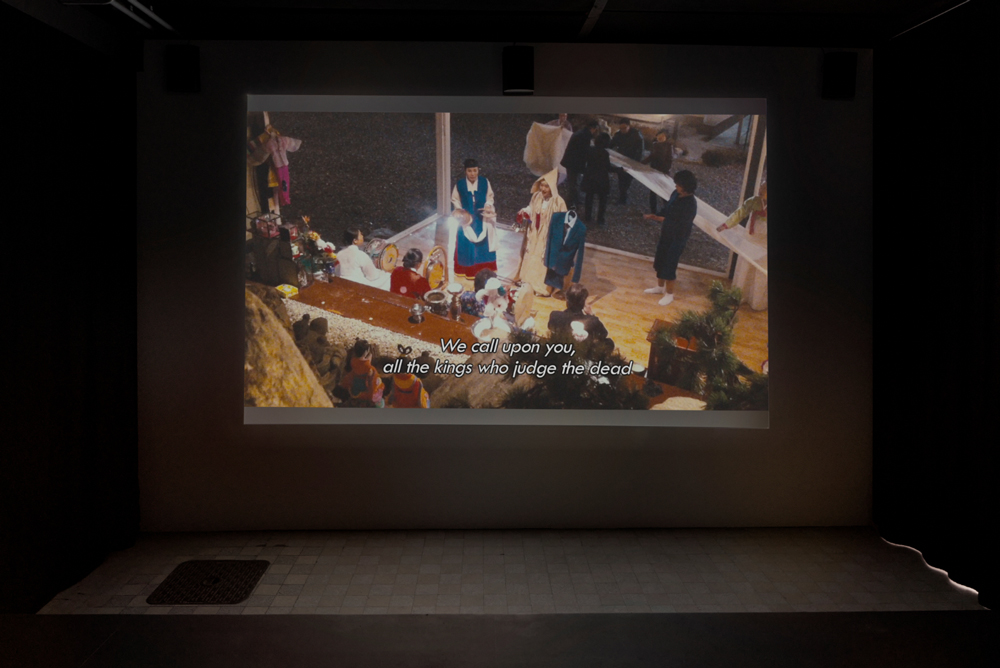

The

gallery was a gut-dang—a shamanic space—where the aesthetics of conjuring and

ritual intertwined, a vessel of prajñā

pāramitā ferrying one from the saha world to the Pure Land.² When the world and its people

are not at peace due to calamity, they are in a state of mi-an (未安)—unpeace—and

thus a gut must be performed.³ When peace returns, an-rak (安樂) is achieved, and that is the realm of purity.⁴ However, the

circumambulating walk from the first floor to the second and back again, like a

pilgrimage or participation in a dwitjeon (back shrine) ritual yard,

was mi-an. Because the ghosts boarding the prajñā pāramitā vessel and the shamanic gut-dang had not yet attained peace.

The

shaman with antlers—the great deer shaman of the gut-dang—was the slide TV. It

is said that the Buddha gave his first sermon at the Deer Park (ṛṣipatana), but another way to see it is that a deer-shaman gave the

sermon there—thus, ṛṣipatana as

a place of shamanic revelation. The message of the deer-shaman was media. With

San-shin (Mountain God), San-ryeong (Mountain Spirit), Sam-seong (Three

Saints), and Chil-seong (Seven Stars)—none of whom belonged in a Buddhist

temple—intervening in the ga-ram (temple compound), the shaman in

leopard print roared, bursting into a lion’s sermon.⁵ That sermon, mediated through

media, was projected onto the wall, delivering the “voice of heaven” [divine utterance or oracle]. In

truth, Small Art History (2014/2017) and Citizen’s Forest (2016) are languages of that sermon.

Art

history is a chronology of images. Chronology cannot escape the narration of

time. To renew that narration, one must either embed image algorithms into it

or fracture time and open the algorithm’s extensibility toward all ten

directions (śífang). Only by negating time can

a heretical language be born. Heresy is trickery. Let us not forget that the

word “art” (美術) originally meant “the

great deer shaman who performs magic.”⁶ When trickery of “meaning” is unfolded in all ten

directions and connected through images, speech is born on the first floor.

That speech could interact in real time with visitors to the gallery. The slide

TV was a telex. In mechanical terms, the telex was a teleprinter-based

communication service allowing direct dial-up between subscribers for data

transmission. Even without a recipient, the telex could automatically print

incoming messages on paper tape. The archive table at the gallery’s entrance

and the deer-shaman telex together had “printed” the image algorithms of Small

Art History as if they were revelations from spiritual

resonance.

One

cluster of “image-speech” (畫語) in Small

Art History relied on a myth of wells that connects foreground

and background. In such a time, where the past and future coalesce, this world

and the next are opened in a single continuity—a twilight hour when “the sound

of the temple bell rings through the cloister, and suddenly / all the men of

the capital vanish, and the world is transformed / into one of only women.”⁷ In France, it is called the hour

of dogs and wolves; in Korea, it is the hour when goblins emerge. It is the

hour when shadows vanish from the well. When the shadow disappears, the depths

below are illuminated. The abyss connects seamlessly with the world above; the

well becomes a singular aperture without sides. The tale of an egg rising from

such a well is told in the Samguk Yusa. Park Chan-kyong draws upon this

and weaves together nianfo rebirth, the verticality of East and West,

celestial ascents, and the “one true mind” of immortality by juxtaposing works

by Kim Hong-do, Ed Ruscha, Hieronymus Bosch, and illustrations from the Chinese

mythology compendium Classic of Mountains and Seas. Min Joung-ki’s Ten

Thousand Pinnacles of Mount Geumgang (1999) is a masterstroke

that brings these mythic and religious perspectives of the well into the plane

of reality. Min not only transforms conceptual narrative into a realism-based

aesthetic but also reveals that a landscape itself can be an image of a “bright

whirlwind.” This whirling landscape corresponds to the feng shui geography of

Sindoan—a circular form of Ja Mi Won Guk (Purple Forbidden

Enclosure), said to be the most auspicious site. This is none other than what

Laozi referred to in the Tao Te Ching as “the gate of myriad

wonders.”

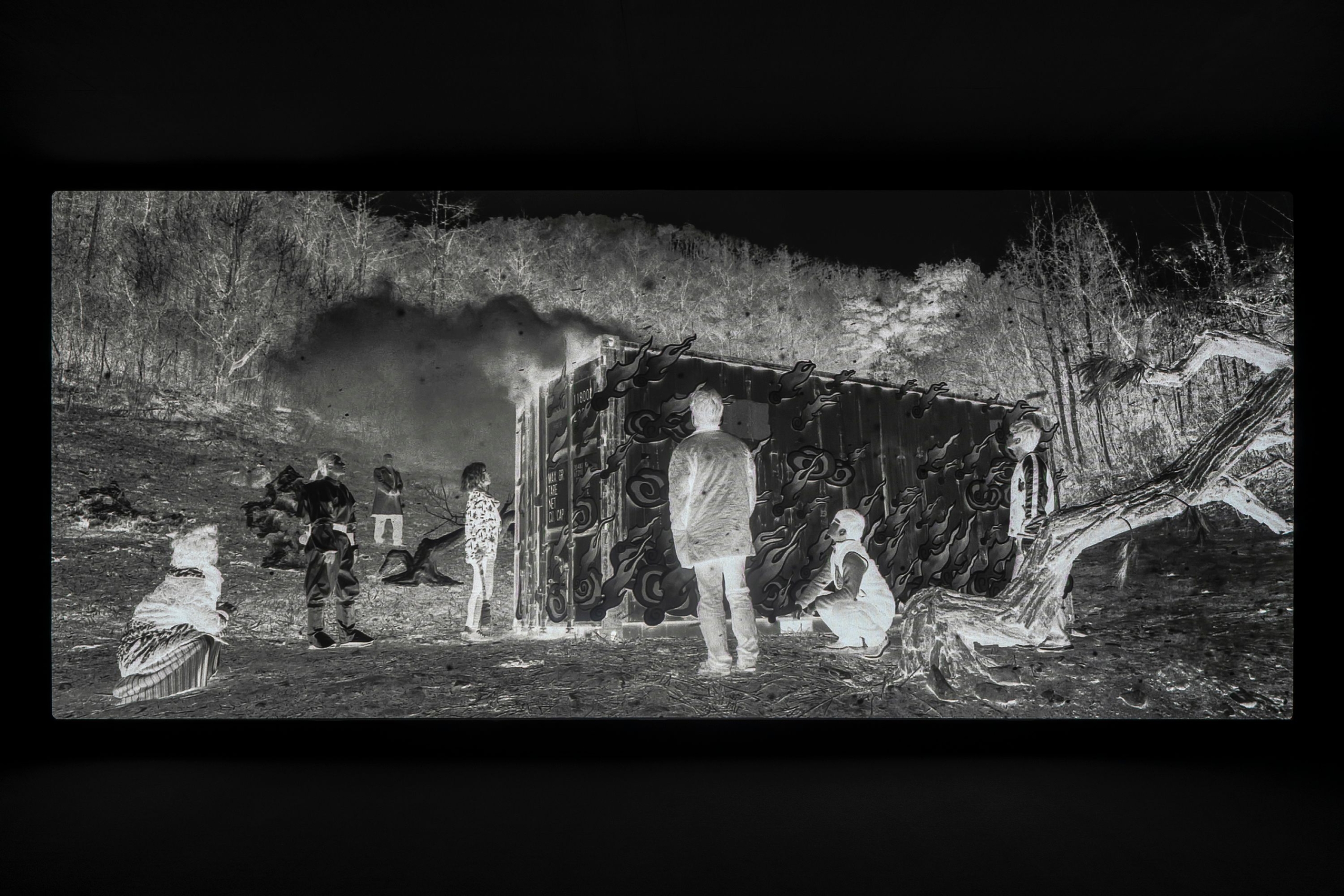

Back

Shrine, 100 Scenes of the Korean War That Made Me Cry, The

Lemures, Military Immortal Crossing the River, Sindoan, Portrait

of Filial Piety, Portrait of Songho,

and Embrace, along with the rest of the plates, are

phantom images of a moment when this world and the next collide upon the

surface of the well. The unfolding of those phantom images into a montage is

precisely what Citizen’s Forest becomes. “No

matter how filthy the mire, it is fine,” said Kim Soo-young. “No matter how

filthy the tradition, it is fine. No matter how filthy the history, it is

fine.” When such mire, tradition, and history are clothed in the imagery of Oh

Yoon, the result is a video composed of fragmented narratives of “countless

reactions.” During the 1970s and 1980s, when Western modern aesthetics had

reached their peak in Korean painting, Oh Yoon created The

Lemures as a gothic counterpoint—much like how Bosch, in the

Renaissance era, parodied the optimism of reason and science through his

paintings of medieval pessimism.⁸ Park Chan-kyong has already referred to this as “Asian Gothic.” For example, in his keynote

lecture at 〈Media City Seoul 2014〉, he emphasized that the world and Asia cannot be viewed through the

framework of the “nation-state.” He proposed observing unexpected

relationships between peripheries beyond Asia and added:

“Like

Claude Lévi-Strauss’s bricolage, Asia is itself a process of transformation

that reconstructs itself through shifts in time and perspective. Chinese

philosopher Wang Hui, resurrecting the postwar Japanese thinker Takeuchi

Yoshimi’s idea of ‘rewinding the West,’ argues that Asia must fulfill the

positive values of Western modernity—such as democracy and equality—more

thoroughly. Wang Hui expresses this with the oxymoronic phrase ‘modernity

against modernity.’ Once freed from the frame of modernity, Asia will become a

space overflowing with ‘strange modernities.’”⁹

Slipping into Tradition, into the Real

Not

only in Korea, but across the foundation of Asian modernity, a complex mixture

of concepts such as colonialism, the Saemaul Movement, anti-superstition

campaigns, tradition, ideological conflicts, Red Army/South Korean Army,

West/modernity, fake reality/actual life, fantasy, modernization/urbanization,

contemporary history, self (individual/subject) and others (the Other),

modernism, and capitalism persists. All of these concepts of modernity

(including “modern” and “modernization”) may be ideological by nature. The sad

shadow of this male-centric and violent ideology is etched deeply into The

Lemures. The fragmented and discontinuous scenes of Citizen’s

Forest revive this shadow. As a cinematic device to pacify the

restless spirits roaming the nine heavens, the gut performed in the film

becomes a shamanic rite—both jin-ogwi gut and shigim-gut. The

extended video, like a long scroll of time, loops from beginning to end. The

conclusion of this appeasement is a Milky Way of Park Chan-kyong-style objects

replacing the symbolic relics of Kim Soo-young’s “countless reactions”—objects

like chamber pots, headbands, long pipes, ancestral tablets, bullets,

copperware, herbal medicine signs, shrines, leather shops, pockmarked faces,

blind eyes, infertile women, and the ignorant.

However,

there is a major difference between The Lemures and Citizen’s

Forest. Oh Yoon’s painting, by deploying a gothic visual grammar

across several frames, drenches the viewer in an emotional state of empathy

with the horrors of modernity. Whether through pathos or resonance, once a

viewer is drawn into the image, they cannot easily escape. In contrast, Park

Chan-kyong’s video does not demand emotional immersion or cinematic absorption.

Viewers may even find themselves expressing discomfort through a sense of

detachment or alienation. This alienation—this estrangement—is as coldly

cynical as the water Bertolt Brecht once poured over his audience. Yet without

such distancing, it may be impossible to gaze directly upon “modernity.”

The Bright

Star and Chilseongdo series,

created in collaboration with Kim Sang-don, originate from the shamanic tool

called myeongdu (明斗/明圖). The symbolic meanings of the myeongdu, a brass ritual

mirror, are dual. The convex front is a mirror, while the back is uneven and

engraved with the sun, moon, seven stars (Chilseong), and Sanskrit characters.

Usually, a string is attached through a loop at the center. The artwork

includes three front-facing and three back-facing versions of the myeongdu,

presented on birch panels painted with dancheong patterns, alongside

works where artificial leopard print fabric is substituted for the center, and

others showing both front and back sides. The inscriptions on the back read:

North Star (北斗), Star-Mirror (星明斗), Seven-Star Mirror (七星明斗), and North-Star

Seven-Star Mirror (北斗七星明斗).

The

National Museum of Korea houses a “Bronze Mirror with Dragon and Cloud

Patterns” from the Goryeo dynasty. Dragons and clouds are shamanic symbols

associated with rain. In Jeju shamanism, the Chilseong god appears in the form

of a snake (dragon). The seven stars are also the seven sons of Princess Bari,

who became stars upon their deaths—this links to the origin stories of

afterlife deities in jin-ogwi gut and shigim-gut. The space

of Bright Star and Chilseongdo corresponds

to a celestial realm, connected to the antlered shamanic telex on the first

floor. Siberian Tungusic shamans wore massive antlered crowns and bronze

mirrors during their sacred rites. Just as prayers are offered to Chilseong,

the shaman acts as the medium of the Seven Star deity—and it was through

the myeongdu, as the corporeal manifestation of that deity, that the

divine face was glimpsed. A viewer ascending to the second floor after

seeing Citizen’s Forest might encounter the bright

spirits of the pacified souls in these “bright stars.”

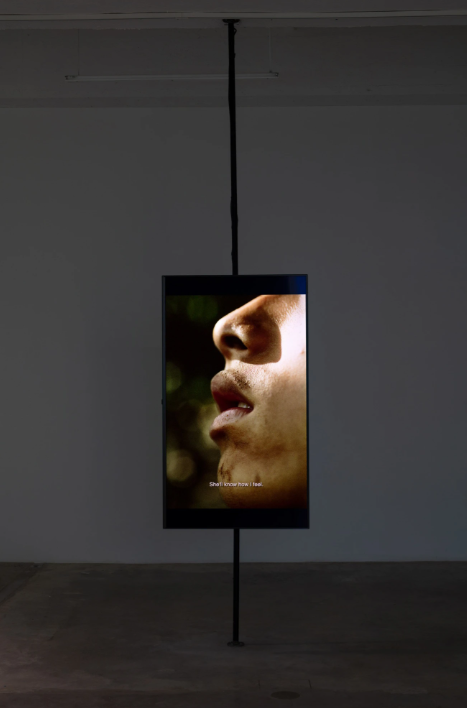

The

Way to Seunggasa reads like a series of steps taken by the

viewer, who has internalized the bright star, along the ascetic journey of a

living Buddha (saengbul). Seunggasa is a temple that enshrines Seungga-daesa,

known as the “living Buddha.” Sitting in a blue or red chair beneath a parasol,

the viewer watches the slide projections. The “I” who chases these images

eventually meets eyes with those on the journey. It is the moment when reality

and unreality intertwine. Under a parasol arranged like

a dwitjeon (back shrine), one prays with makgeolli for blessings,

draws a myeongdu, and interprets the fortune based on the number of grains

of rice. In that instant, “I” become them, the viewer, the Seunggasa monk, and

the shaman—a curious transformation.

Come

to think of it, we forgot MoonWalk by Michael

Jackson. Why, then, did Park Chan-kyong suddenly insert MoonWalk so

incongruously? Perhaps it was to suggest that, after that strange experience,

time no longer moves toward the future, but rather slides into an invisible

real—called tradition.

Published in the Fall 2017 Issue of 〈Hwanghae Review〉

—

¹ Based on the press release distributed by Kukje Gallery.

² The boat of prajñā pāramitā is also

known as panya-yongseon (般若龍船). The main hall (daewoongjeon) in a Buddhist temple compound

(ga-ram) symbolizes this boat.

³ In classical literature, “an-nyeong” first appears in The Book of

Songs (Shijing): “When war is pacified and peace (an-nyeong) arrives…”

In Zhuangzi, it is written: “Desiring peace for the world, he saved the

lives of the people.” It was not originally a greeting, but a word meaning

“peace.”

⁴ When one is not at peace, one is in a state of mi-an (未安). An-rak (安樂) means peace and

bliss—equivalent to Anyang Pure Land (安養淨土).

Park Chan-kyong presented I Want to Be Reborn, in Anyang as

part of the Anyang Public Art Project in 2010. The city name “Anyang” (安養) is itself borrowed from the Buddhist term for the Pure Land. Park

interpreted the ideograph “An” (安), where a woman stays

at home, wears a hat, and when inverted, appears to be hanging, as melancholic

symbolism of Anyang as a city of mi-an, an unpeaceful modernized town.

⁵

During the indigenization of Korean Buddhism, Mountain God Halls (Sanshingak)

and Mountain Spirit Shrines (Sanryeonggak) were incorporated into temple

complexes. The Mountain God (Sanshin) is typically depicted with a tiger.

⁶

The character 美 (“beauty”) is derived from

“great deer antlers,” symbolizing the ancient shaman. 術

(“art” or “technique”) originally referred to magical skill and those who

wielded it—called bangsa (方士)

or jin-in (眞人).

⁷

Kim Soo-young, 〈Colossal Roots〉 (1964), from Colossal

Roots, Minumsa, 1974.

⁸

Bosch was criticized by Renaissance contemporaries as a “Gothic Revivalist” or “Medievalist.”

⁹

Park Chan-kyong, “Ghosts,

Spies, and Grandmothers—Theme

as Pattern,”

keynote lecture, Media City Seoul 2014.