I have a memory of crying so bitterly before a family photograph

taken prior to my younger brother was born. While growing up, I was always

possessed by the question of why I had been so sad before a harmonious looking

family photograph. Once, I thought that it was due to a complex specific to a

second daughter who tried to find the ideal of a family in a family in which

the younger brother monopolized my parent’s attention. And also, right after my

father had died in my elementary school days, I had a self-reproach presuming

that my cry might have been a premonition of his death.

Of course, after growing up, I realized that ‘the death of a

photograph’ preceded the real death of my father and every photograph pre-experienced

death the moment it was born. Now I know that the sadness I felt about that

photograph was associated with the above mentioned reasons, such as social

psychology, enchantment, and the basis of photography aesthetics. But not all

my curiosities have been answered. In most of the cases, the size of senses

felt in a photograph far exceeds the sum of all the explanations about it.

Indeed, numerous particles of signs constructing a photograph ceaselessly

refuse to be anchored and repeatedly yell, “realign yourself!”

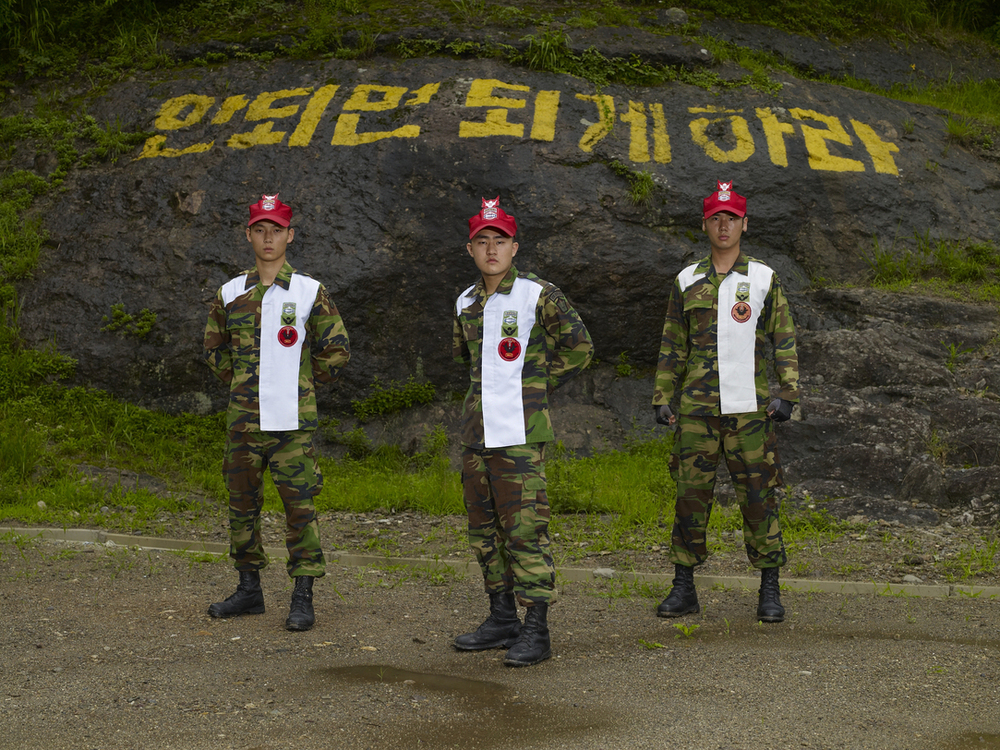

The reason why Heinkuhn Oh’s portraits look unfamiliar to us is

because his works begin where my original experience of the photograph deviates

from them. For a casual glance, he just seems to aim at azummas we usually

encounter on the street. They are social beings specific to Korea who are

composed of the combinations of the specific age, sex and class. Though they

just began to draw attention of a few researchers of cultural studies, they

still tend to carry a negative nuance. Especially for me who just passed my

mid-thirty, the moment I am called an azumma, I feel a little bit hurt. When

that appellation is affirmed to be grounded upon an objective choice without

any malicious intention, that hurt lasts longer. In other words, an azumma is a

category of an appellation that calls for evasion or dissimilation from it

rather than assimilation or sympathy toward it. This tendency is all the more

striking considering the ambiguous feeling attached to the appellation of

mother.

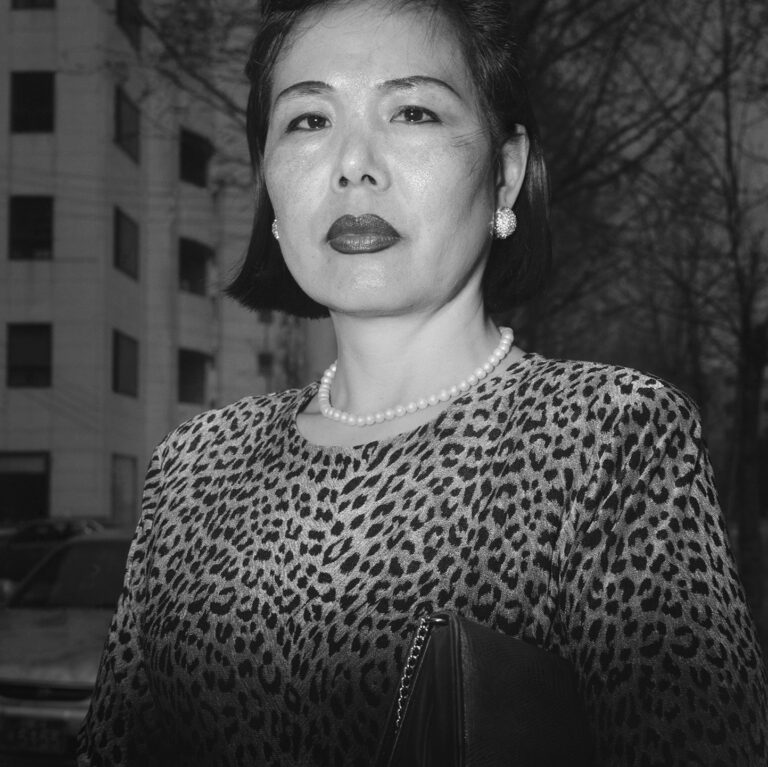

On the other hand, when I find an azumma among Oh’s azumma

portraits who looks exactly like the mother of one of my friends, I realize

that the azumma is an appellation used to call a relative or an acquaintance.

‘Aunt’ as an appellation for a close friend of a mother, or ‘mother’ as an

appellation for a mother of a close friend, in other words, a fake aunt and a

fake mother, surely reside in the spectrum of the azumma. We have agreed to use

the appellation of aunt or mother even when it referred to a relation which was

not a blood relative in order to shed a negative connotation of the appellation

of azumma. The shrewdness of Oh’s photographs lies in his decision to look at

all these azummas who must be surely someone’s mothers as azummas, not as

mothers. Through an azumma picture, not that of a mother, and through an

acquaintance, not a family member, Oh comments on a ‘fake photograph’.

Furthermore, he decides to say anew about the photograph.

The photograph in our daily lives, in itself, is synonymous with a

family member or the memory of a family member. Especially for us, who

experienced the disintegration of a large family and its displacement to a

nuclear family in the process of modernization mottled with rapid demolition

and shaky reconstruction, nothing can take the place of a photograph as an

effective substitute of memory. Ranging from a multiple picture frame in a

country home to a lavishly bound wedding picture album which is a necessary

item of a wedding, the photograph does not only enhance the sense of belonging

but also functions as a support of everyday life. And also, ranging from an old

black and white photograph on top of a signboard looking for a lost family

member to family portrait displayed at a commercial photography studio, the

photograph enhances the sense of community and offers an ideal

type for it. It is also difficult to deny that the strong experience of a

family photograph defined the way in which the photograph in general is

received.

In that sense, the saying, “what is left is only the photograph”

is our honest confession about photography. In Korean context, the photograph

is the record of an everyday life and at the same time, reversely, a kind of

cement that fixes our reaction toward the entire world. Perhaps in no other

region in this world is the bondage between the photograph itself and the world

facing it so bragged. Sticker pictures occupying the back cover of kid’s

notebook are nothing but the proof of this bondage.

At this juncture, once again, Oh’s pictures come to us as

something unfamiliar. In his azumma pictures, the kinds of sentiments we

thoroughly practiced through family photographs such as the sadness of

perceiving ‘the moment of death,’ the nostalgia for the time of the past and

natural compassion and sympathy toward the life of a specific person are

excluded. More exactly speaking, such sentiments have already been withdrawn.

Though the trace of such sentiments still remains, Oh is masquerading himself with

the distance toward them and intended coldness. After all, Oh’s azumma pictures

reflect his attitude of calling a fake aunt or a fake mother. Indeed, while we

call her in a very familiar manner, we still keep a certain distance toward her

so that it does not matter very much even if we could not recognize her on the

street in the future. Because of this internalized distance, the azummas

‘represented’ by Oh are wearing very familiar, deja vu faces. Yet overall,

these faces take on a strange, grotesque and even surrealist mood. This

internalized distance might especially differentiate Oh’s azumma pictures from

portraits by other Korean photographers.

However, the fascination of Oh’s photographs does not only lie in

his picking of hitherto unnoticed being in our society that was not brought

forth as an object of photography and offering it in his own style. Above all,

he does not differentiate between the matter of what to take picture and how to

take picture. When we find out that his pictures are not about the azumma but

about her signs, these matters will be spontaneously dissolved.

A closer look at his pictures tells us that Oh is an avid

collector of all the components that enable us to call a woman an azumma, such

as accessories, pattern and texture of her clothes, hair style and makeup. It

is also revealed that Oh is a keen physiognomist who can let us guess an

azumma’s character, family relationship and occupation by classifying wrinkles

and looks of her face. He even resembles a fortune teller with a high hitting

ratio who can work off her grudge and somewhat predict her future. Of course,

there is no confirming whether the azumma Oh ‘took’ picture really belongs to

the social category he classified or not, whether ‘the insurance saleswoman

type’ really is working in that field or not. His works are persuasive insofar

as he decides to look at the azumma in such a way and she actually looks so. In

this context, his works aiming at fake aunts and fake mothers are surely fake

photographs.

On the other hand, Oh’s typology in which the general and the

individual, the specific and the universal intersect in turn are related to the

dialectics of difference and identity well versed in photography. For instance,

one of Oh’s works Two azummas 1 ) is positioned exactly at a

point opposite to Diane Arbus’s Twins. While Arbus’s picture is trying to

revive the voice of difference hidden inside the category of identity by

putting a scar to biological symmetry of the twins(footnote 1),Oh’s azummas,

who are not related with each other yet look like sisters, let us discover ‘a

social genotype’ that lies across the difference. Jittery eyes, wrinkles around

the mouth and glittering makeup that these azummas share who are in an

asymmetrical relationship with each other in terms of the age, body and their

characters are clues to the career of their common lives. If we put an

azumma wearing glasses and an azumma wearing glasses with

thick black frame and then put another pair of azumma

pictures next to them, these clues will be increasingly strengthened.

The association of these images exposes the ideology of typology

that nullifies the particular personality and at the same time instantly

condenses some common social experience beyond the competence of an individual.

Unlike azumma pictures, ajussi (the generic term for man) pictures have a

higher risk of failure because they are more likely to be read as an expression

of personality rather than as an interpretation of stereotypes. The category of

agassi (the generic term for young lady) is difficult to establish because the

trace on a human body left by social time and a shared experience decipherable

from it have not yet been formed in her.

Unlike with agassis, with azummas, the tension of confronting this

world, especially the aesthetic tension, is totally loosened. “The tangled hair

in permanent wave, loose skirt and dragged slippers” are the signs refering to

the loss of this tension. Oh reconstructs those azummas who lost their

aesthetic tension into aesthetic objects. Especially, while eliminating the

individual context in which each azumma is located, Oh brings them forth in

full rig.

In most of his works, as the background and lower half of the

image are blackened and a strong flash of light is cast on the face, an

unnatural dividision of an image occurs. So, the overall scene is flat,

partially fragmented and also ambiguously overlapped. This space demands us to

grasp it in an ‘analytic’ perspective rather than in a ‘synthetic’

perspective.(footnote 2) azumma’s half-body portrait abruptly rising above the

background in fade-out above all reveals the lonely and desolate sense of being.

On the other hand, the glitter of fake jewelry scattered here and there all

over the scene expresses azumma’s naivety. The nap left on a jacket, pattern

and texture of a dated blouse, just like wrinkles around the neck that could not be camouflaged by makeup, remind us of the power of

dailiy life.

But as my eyes come across azumma’s eyes floating over the image,

I feel momentarily stunned. I don’t know how the photographer could ‘disarm’

azummas, but they are exposing their whole being without any exaggeration. We

can never feel the tension of confronting a camera or firm will to resist the

captation of one’s identity by the lens. They are also posed in a manner

completely distanced from the effort and awkwardness of young brides being

taken picture for wedding ceremony, or from the struggle to efface even such

awkwardness. Without any regret about their young days, jealousy toward other

young ones, or shame at their own face getting older, these azummas are boldly

getting rid of their own self-consciousness.

As I am in confusion regarding how to interpret azumma pictures,

along with the collapse of social aversion to azummas, the composition of the

image gives me a clue. The flat composition of the image that does not suggest

any three dimensional volume corresponds exactly to the depthlessness of

self-consciousness, the darkened outer rim looks like another frame within the

frame. These pictures look like a meta-discourse to azummas, ot still image of

a film.

Susan Sontag remarked that the relationship between the

photographed world and the real one was as inaccurate as that between a firm

still and a film. The photograph is defined by important details captured in a

moment and fixed for good, whereas the life is not.(Footnote 3) In a different

context, Oh’s photographs are similar to film stills. They are film stills of

actresses appearing in an imaginary movie produced only inside the imagination

of the photographer. These actresses are of course far from ‘stars’ who end up

overacting from too much self- consciousness or are always stressed by elements

other than their own performance. They are, rather, extras, amateurs or persons

with real jobs. Without distinguishing their role in the drama from reality, azumma

actresses in Oh’s ‘still images’ perform in a realistic manner and leak out the

reality of life.

Finally, it has become apparent that Oh’s azumma pictures are not

‘azumma’ pictures but azumma ‘pictures’. So, when confronting his pictures, I

am caught by a zestful energy that is not experienced when looking at a family

photograph. In many cases, a family photograph is, rather than a family

‘photograph’, a ‘family’ photograph that puts one under a psychical burden. To

the contrary, Oh’s azumma pictures free us from this sentiment of kinship

experienced in the real world. Nevertheless, no one can say for sure to where

the power of cultural identification that we have practiced through these fake

photographs of fake aunts and fake mothers will lead us.

Footnotes

1. “Biology, Destiny, Photography: Difference According to Diane

Arbus”, Carol Amstrong, October 66/fall 1933

2. “Photography’s Discursive Space”, The Originality of the Avant-

Garde and OtherModernist Myths, Rosalind Krauss, MIT press, 1986, p. 135

3. On Photography, Susan Sontag, 1986, P 105