Bae

Young-whan is someone who sees life without illusions. His compassion and

comfort, therefore, run deep. He weaves stories by intersecting sound and

spectacle, as in Popular Song. The Way of

Men features guitars made from discarded mother-of-pearl

cabinets and wooden boards, so they cannot produce proper sound. Once symbols

of youth and rebellion, these acoustic guitars have, in the “way of men” that

demands success, status, and patriarchal duty, become mute—guitars in form

only. This lineup of men expressed through such guitars is quaint yet evokes

pity. While The Way of Men retains only sight and

loses sound, Worries – Seoul 5:30 p.m. retains

only sound and loses sight. This piece plays only the sound of temple bells,

without showing the bells themselves. It combines bell sounds from twelve

temples around Seoul, rung between 5:30 and 6 p.m., a time when they toll to

console all beings. Yet we neither hear them nor remember that such objects

even exist. “Wouldn’t you look for a bell more desperately when you can’t see

it?” the artist says.

Perhaps,

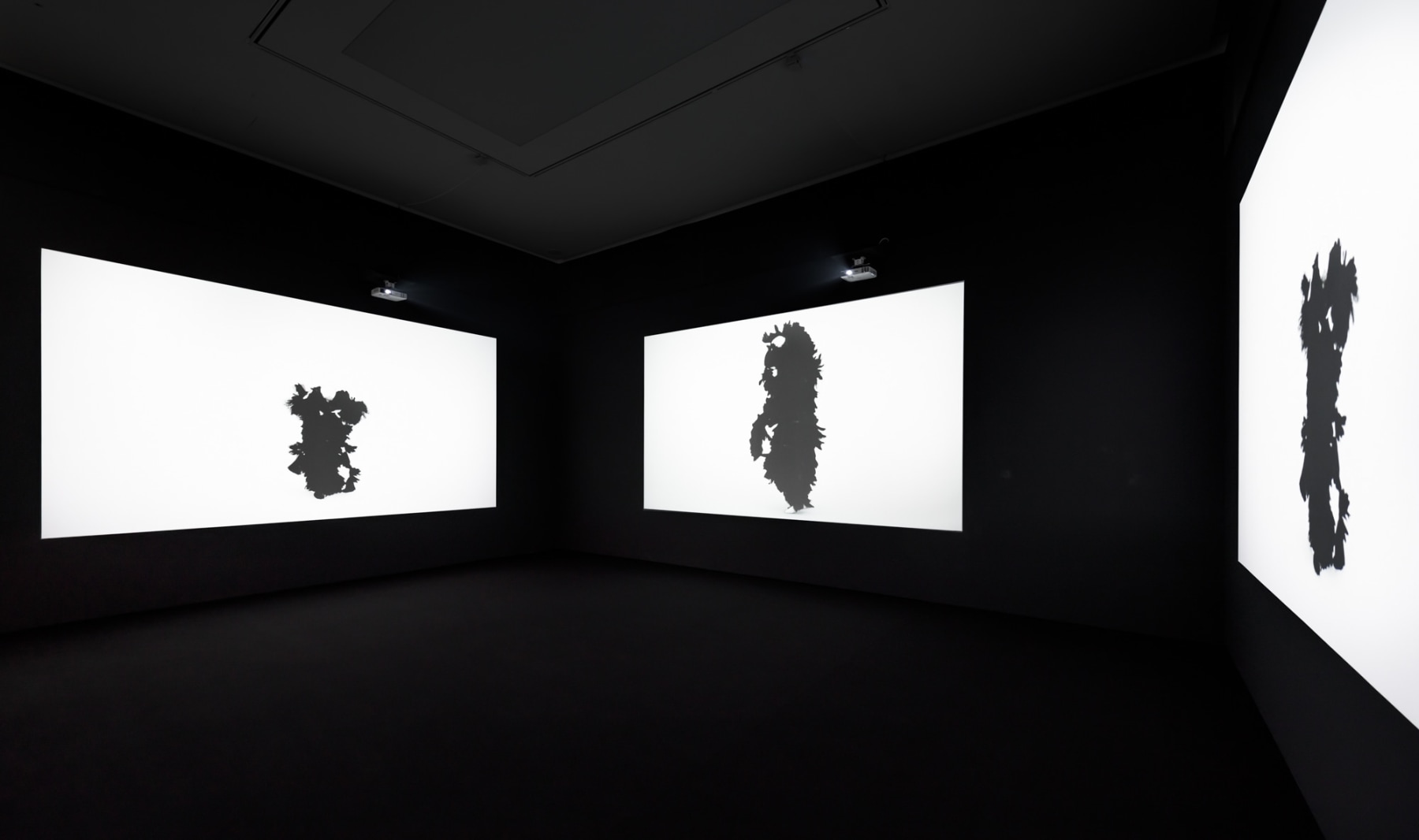

as he suggests, the answer lies within oneself. His work Autonumina—meaning

“self-sacred”—is an attempt to find that answer. In typically witty fashion,

Bae measured his brainwaves and kneaded clay by hand following the waveform,

shaping mountains. That the brainwaves take the form of mountains signifies, he

argues, that there exists within humans a “sacred part” identical to the

mountain’s form, long regarded as a symbol of goodness and perfection. As in

the story of “The Great Stone Face,” those who seek greatness eventually find

it within themselves. Such self-affirmation is the first step toward affirming

others.

“These

days, people don’t want to read uncomfortable novels or hear serious stories.

The breakdown in dialogue is severe. This exhibition, at the risk of

embarrassment, is meant to provide a ‘starting point’ for conversation.”

His

proposed methodology for communication is the concept of “abstract verbs.” Like

abstract nouns, they invite us to read the deep, unseen meaning behind actions.

“For

example, suppose a child locks themselves in a room. The true meaning of that

act is ‘I want to talk.’ We should look at the real meaning embedded in

actions. It’s not about slogans, but about action and practice. This is, in a

way, a definition of art. Art without genuine content is hollow.”

And

he acted on this. He undertook a project to build and donate libraries in

places lacking such facilities. For an artist to build and donate a small

library is, in itself, ironic. What matters is not the donation itself, but

that no one else was doing it—so the artist had to. In August last year, he

visited Fukushima, when the fear of nuclear disaster was still vivid, and later

presented The Wind of Fukushima, a work sharing his

reflections. Confronted with an event that was both a regional and a human

crisis, he realized how indifferent we are to the suffering of others, and how

we treat misfortunes that could happen to anyone as someone else’s

problem—prompting him to reaffirm an artist’s duty. For Bae Young-whan as a

conceptual artist, the most important thing is the sharing of thought.

“I

only say things that are common sense. But people find that strange. The fact

that common sense is strange shows how much we live in a false world. My

exhibition shows what everyone knows but chooses not to recognize.”

If

the golden ring at the entrance is to possess the true eternity and glory of

gold, it must be a ring not for competition and confrontation, but for

dialogue. Until the moment all wounded hearts find comfort, the bells will toll

without rest, and the popular song will continue to be sung. Everything is in

our lives—and Bae Young-whan’s work stands beside them.