Messenger/Angel/Media

In The

Legend of Angels, French philosopher Michel Serres evokes the world as a vast

array of flows:

“Winds

generate flows of air in the atmosphere; rivers draw flows of water across

land; glaciers carve hollows through mountains and valleys to make solid

rivers; rain, snow, and hail are flows of water through the air; currents are

flows of water roaming the seas; volcanoes thrust vertical flows of fire toward

the sky or into the ocean; lava and mud are lands of hot and cold liquids

traveling across the earth. Continents drift as carpets of land floating on

fire… One element passes through others, and conversely they pass through it.

Elements endure and transport. These correspondences of flows produce a nearly

perfect mixture, a kneading together, and thus there is almost no place that

remains ignorant of conditions elsewhere. Through messages, flows receive such

knowledge.”1

Serres

calls the beings that convey a place’s message to another place “messengers,”

or angels. Not only winds, rivers, rain, and hail, but humans—and the

institutions and technical devices humans create—also belong to these

messengers:

“The

word angel comes from the ancient angelos, meaning messenger. Look around.

The flight attendants and pilots, the radio messages, all the crew who arrive

from Tokyo only to depart for Rio de Janeiro, the fifteen planes lined up,

noses neatly aligned, ready for takeoff, the yellow postal trucks delivering

letters, packages, and telegrams, the calls on the PA system, the endless

procession of bags passing before us, the announcements that ceaselessly seek

Mr. X or Ms. Y just arrived from Stockholm or Helsinki, the instruction to

board for Berlin, Rome, Sydney, or Durban, the passengers crossing paths,

hurrying toward shuttle buses and taxis, the escalators that continuously bear

us up and down at their own pace like Jacob’s ladder… Iron angels carry angels

of flesh and blood, and angels of flesh and blood send signal-angels out on

broadcast waves.”2

I

have long thought of Minouk Lim’s practice as the work of angels in Serres’s

sense—a “media” practice of messengerhood. “Media” occupies the in-between,

mediating beings to let them flow toward one another: a medium that transmits

waves or physical actions from one place to another; a spirit medium that

mediates between the living and the dead; a medium that brings messages and

information into contact with our sensory organs. These words share the same

root, medium/media, for good reason. Lim is a “media” artist who creates

flows between here and there, between one being and another, to

mediate/mediate/bring them into encounter.

In an interview with curator So-Yeon

Ahn, Lim remarked, “What is called ‘media art’… intrudes upon the definitions

and boundaries we call ‘borders’ and raises problems.”3 Her media art summons a

community in which, as Serres says, there are “almost no places that do not

know the conditions of others,” by causing beings of nature, history, and

reality to cross borders and flow toward one another. In another interview, the

artist described her work as “tracking what has disappeared, what is invisible,

encountering them, and once again questioning them.”4 She chose art as the

method of encountering what is gone or unseen because art is “a way that can

flow, permeate, and vanish.”

“I

do not fix my identity as an artist beforehand, brooding over it, or make work

to enlighten anyone about an artist’s social duty. My ultimate concern is

existence; my questions point toward something more fundamental. Where did we

begin? Water? Fire? Some microorganism, a star, the universe? In the midst of

mysteries that refuse to be solved—sorrow, warmth, memory—I believe art is the

only language that protects rather than excavates. Unlike advancing only in

what we know, we must also proceed, practice, and struggle in the face of what

we do not know… Rather than judging, dividing, or presuming to know, rather

than trying to conquer because we ‘know a little,’ I wish to speak through

methods that can flow, permeate, and vanish—because I am an artist. Ultimately,

this is how we encounter what is invisible, what has disappeared.”5

Media as Flow

To

flow, permeate, and vanish—and thereby meet what is invisible or gone. There is

no shortage of evidence that Lim’s practice is a media practice in this sense.

Almost all of her video works feature flows. A truck carrying a rapper flows

through the city (New Town Ghost [2005]); a cab whose

driver defends the era of state nationalism flows through the darkened streets

(Wrong Question [2006]); a boat carrying viewers flows

along the Han River ((2009)); people’s hands flow across a singer’s body (The

Weight of Hands [2010]); and containers carrying the remains of

the dead flow along Korea’s highways (Navigation ID [2014]).

Speaking of the two-channel work The Possibility of Half (2012)—which

juxtaposes mourners at the funerals of Kim Jong-il and Park Chung-hee—Lim says:

“I

had been interested in movement, vehicles, and flows, and I reconsidered the

fact that tears flow from the body as a result of transference. What is it that

moves and melts? … A corpse feels no pain, sheds no tears, and does not move.

To be alive is to suffer pain, and pity arises as a facet of the

human distinct from animals. Yet what moves flows into somewhere else,

producing an unstable and uncertain state with subversive potential.

Tears are evidence of overflowing joy or sorrow; they function in both

directions. In the divided situation of North and South Korea, I saw,

paradoxically, that tear ducts are a joint zone. Those ducts surge up and run

dry from each other’s losses, perpetually battling to empty and fill. So I

wanted to compare the two kinds of tears and find what is common.

The

two-channel projection of The Possibility of Half formally

expresses a kind of fork in the road of tears. I wanted to imagine the moment

when the potential of tears is subverted and begins to flow. Unification is not

becoming one but rather the recovery of flow, is it not? That flow is closely

tied to beauty, and in tears that flow we can think of where we come from and

where we should go—hence the title The Possibility of Half. The tears of a

scattered community flow out of longing; in the future, I imagine those flows

breaking through what is blocked and overflowing with rejoicing.”6

The

artist’s belief that flows, by entering somewhere, create unstable and

uncertain states—and thus possess the subversive force to break what is

dammed—can be read elsewhere. In Portable Keeper (2009),

an object joins a feather to a fan propeller. A propeller moves invisible air

to produce a flow: it sends the air before it backward and the air behind it

forward, condensing the air to generate a stream in the unseen atmosphere.

That

stream sets in motion what is ordinarily still—at times even allowing things to

fly. Birds, for instance, entrust their bodies to currents of air via feathers,

flying from here to there. In Monument 300—Chasing Watermarks(2014),

a project to search for 300 people presumed to have gone missing during the

Korean War, participants circled snowy water facilities to find feather-objects

the artist had hidden. Sensitive to air currents, the feather served as a

medium seeking to receive the condition of departed spirits.

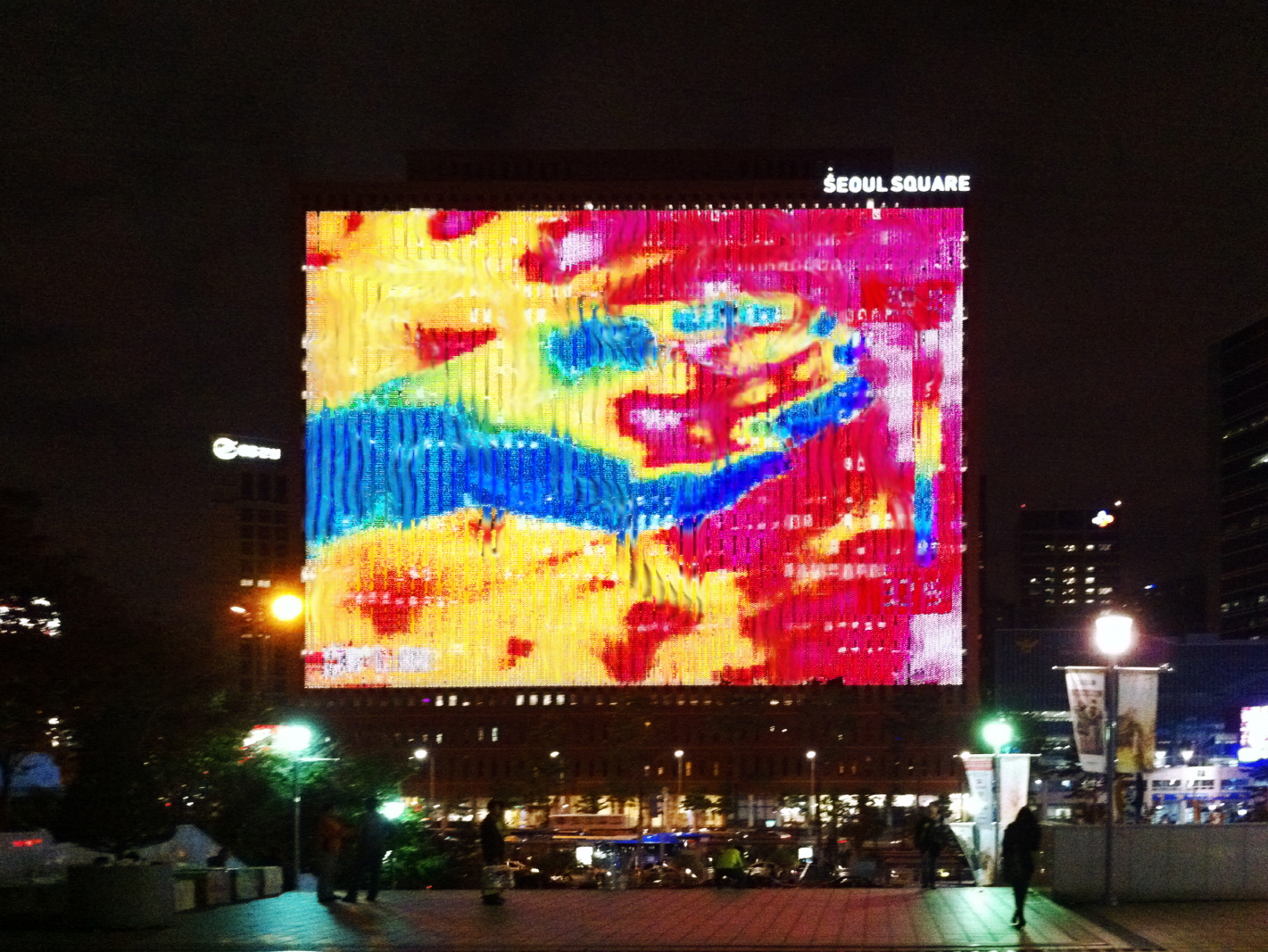

And

what of Lim’s favored thermal-imaging camera? It visualizes body heat unseen by

the naked eye. Body temperature is an invisible flow between people—and a

message that they are alive. Thermal cameras render this constantly changing,

easily vanishing heat visible through movements of color, allowing us to grasp

the state of bodies. The artist links this camera—which “captures omnipresent

yet unseen heat, converting into color the infrared energy emitted by every

thing and space, pixel by pixel”7—to art’s sensibility. Unlike the optical

technologies of scientific civilization and the media power of consumer society

symbolized by “light,” it is a medium that recalls a tactilely sensed

flow.8

Container

Anyone

who has followed Lim’s work will remember one object that appears with unusual

frequency: the container. In ‘Lost?’ (2004) at Maronie Museum, the

artist installed two empty containers beside the museum in succession. Through

these container—like field offices—she created a place where exhibition

personnel, passersby, unhoused people, and unplanned visitors could briefly

rest. In line with the show’s title, the container became a media that created

a flow (rolling) of people by offering an improvised resting space.

A

container is, originally, a thing designed to carry goods over long distances.

When I returned to Korea after studying abroad, I packed my belongings by the

cubic unit and loaded them into a container. Thanks to that, my things born in

Berlin crossed the sea to the customs yard in Incheon. The container is thus a

temporary dwelling for things that need to flow from one place to another. In

Korea, however, containers also serve a range of uses for people: on

construction sites, they often function as workers’ rest areas and canteens,

and at times as temporary field offices or living quarters.

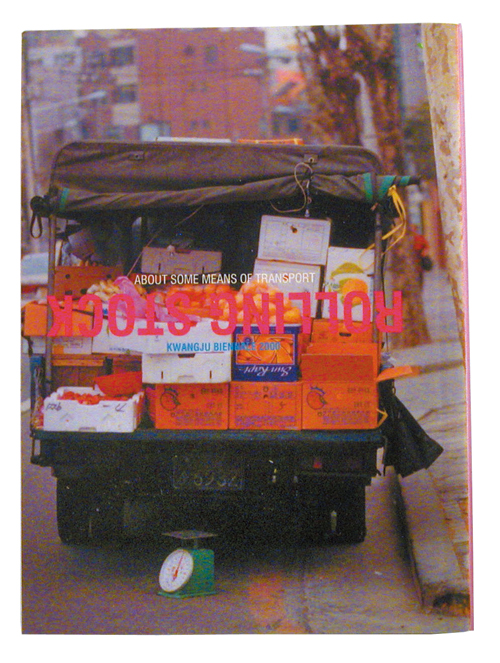

In Navigation

ID (2014) at the Gwangju Biennale, the temporary and mobile

nature of containers was central. Lim live-broadcasted via the internet the

scene of containers holding victims’ remains traveling the expressway to

Gwangju. It was a symbolic attempt to restore flows blocked by the residues of

history—ideological conflict, war, division—further knotted by regional

antagonism between Yeongnam and Honam. Upon arrival, two containers sat in the

middle of the Biennale’s vast plaza. Containers—temporary dwellings required to

move things from one place to another—now held human remains.

The bones,

unburied for lack of proper funerary rites, were stored in the plastic bins

used for moving household goods, placed with desiccants on steel racks. To me,

the containers appeared as a compromised rite. A container of remains, in

itself, profaned the ritual solemnity due to the dead. The container’s

temporariness and mobility made the remains look like items stockpiled on a

construction site or luggage bound elsewhere. What blocks the remains from

flowing toward their proper place? Here the container uncomfortably renders

visible the problems of our history and politics that obstruct the dead’s

passage. When will these yet-unnamed remains be released from their temporary

dwelling in a container to be properly mourned?

Broadcast Station

The

messenger-like media that let here and there flow toward one another—so each

can know and sense the other’s state—also exposes, and ultimately seeks to

overcome, what dams those flows, making visible and sensible what has vanished

or cannot be seen because of such blockages. I have called Lim’s practice

“media art” in this broad sense. It is not surprising, then, that the devices

we customarily call “media” stand at the center of such work. Cameras, for

instance, make images flow from one place to another, allowing what could not

be seen here to appear and enabling encounters between here and there—the

device of the “between.” In Navigation ID, alongside a

camera mounted on a helicopter, LTE mobile phones were used as media “to

console the wandering souls of the missing and the dead and to amplify hidden

voices.”9

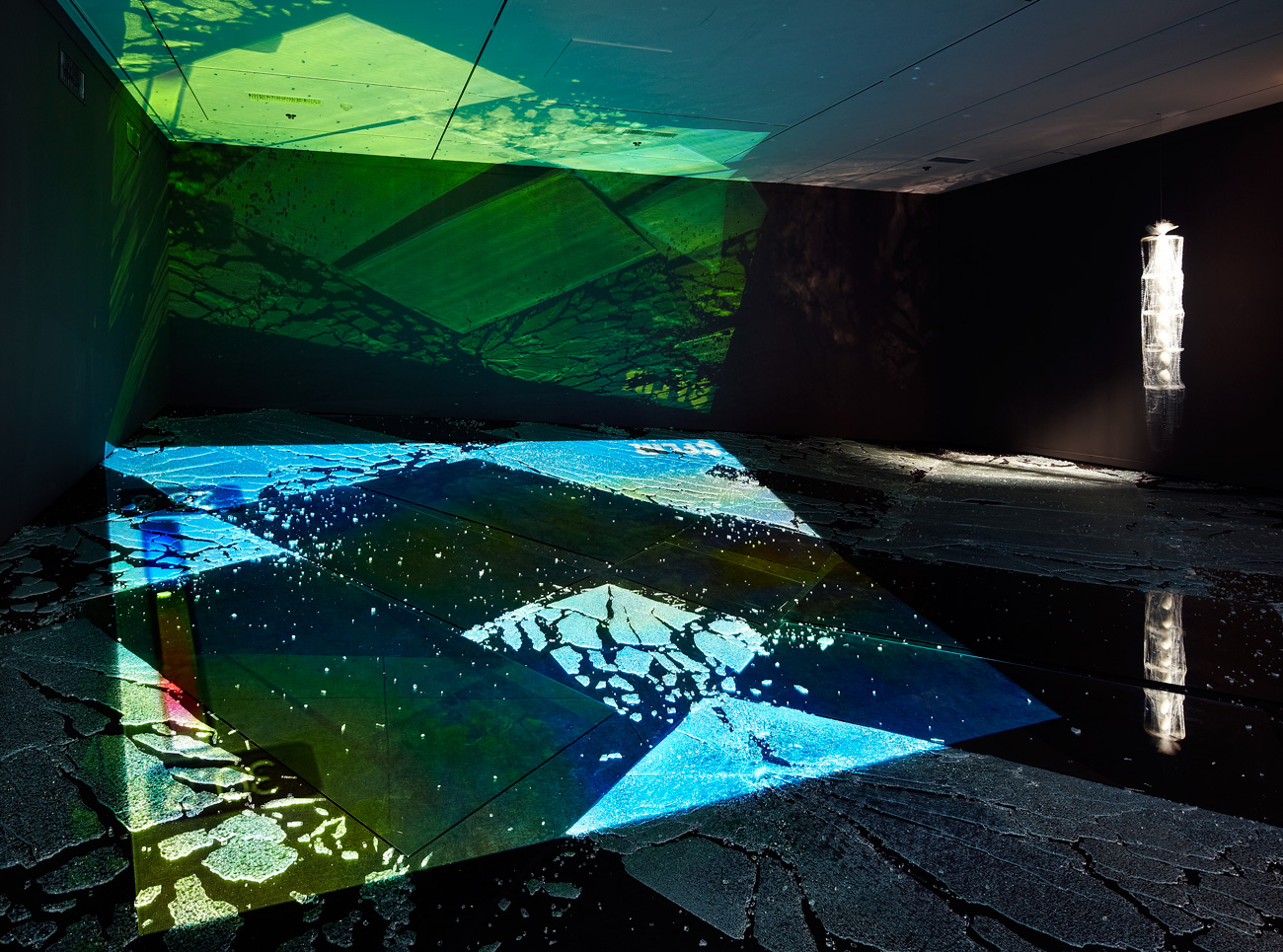

In

her new work Running on Empty, Lim installs a broadcast

studio with the camera at its center. A container whose volume has disappeared,

leaving only a facade, hangs precariously in midair, tied with white muslin

cords; a camera hangs from a timber jib, aimed at it. Around them, lighting

stands, boom microphones, and reflectors mingle with feathers, buoys, and nets.

What does this camera capture? Where do the images it frames flow? To glean an

answer, we must move into the next room.

There,

Lim projects The Promise of If, her edited footage of

KBS’s 1983 live broadcast Finding Dispersed Families, inscribed in

UNESCO’s Memory of the World in 2015. Along with the 1979 funeral broadcast for

former President Park Chung-hee and Nam June Paik’s 1984 satellite show Good

Morning, Mr. Orwell, it was among the most indelible media images for Lim.10

In Finding Dispersed Families, cameras panned across faces holding

placards at regional stations, sending them to viewers elsewhere. In the process,

there were moments when people who did not know even the names or ages of their

separated kin “recognized one another at once, by feeling and intuition, upon

seeing the screen.”11 It was a moment in which media

literally appeared as that which makes here and there flow into

encounter. It is natural that this broadcast remains a deep memory for “media

artist” Lim.

In Running

on Empty, Lim seems to recall this “very instinctive and sensuous,

paradoxical experience of media space.”12 A container—an object that creates

flows by carrying goods from one place to another—is, as the artist notes,

“currently the only thing that still moves between North and South Korea.”13

Yet the container suspended in Running on Empty is

flattened, unlikely to hold anything or anyone. Together with the human-shaped

objects made from tree roots and agar, it resembles an altar from a cargo cult.

What do they await before this container-altar? Are they trying to grasp a

signal emanating from the container—so faint as to be barely detectable? To me,

the objects and camera encircling the container call forth the “paradoxical

experience of media space” that Finding Dispersed Families made

palpable. That experience, unsettling the impossible border of division, might

let different places flow toward one another.

The Promise of If

Lim’s

media art does not avert its gaze from the problems of our reality toward a

beautiful imaginary world. I believe this follows necessarily from her media

practice, which seeks to subvert what is dammed and congealed through flow. In

this exhibition, Lim focuses particularly on the condition of division. She

says the media image of the live broadcast Finding Dispersed

Families made her consider “what an artist is in a country still at war,

where identity is fixed through enmity, in a divided nation where tension

cannot be relaxed; what it is we long for; what media is.”14 Indeed, war and

division—and the physical and ideological enmities they produce—are the direct

causes of the missing in Monument 300—Chasing Watermarks; the reason the

remains in Navigation ID must still lie in

containers; and the starting point for why the tears in The

Possibility of Half assume a political charge.

Division keeps us

from “speaking as we think,” forbids the hospitality of those marked as “our

enemies,” and allows the imagination of communities “ceaselessly erased and

made invisible at the edges of linguistic, regional, familial, and national

communities”15 to subsist only as an “if.”

Unification

Contour imagines that “if” in a paradoxical form. Above the

facing contour lines of Baekrokdam and Cheonji (the crater lakes of Hallasan

and Paektusan) perch collapsing architectural fragments from South and North,

clinging to substitute the peaks. If we recall Lim’s remark that “unification

is not becoming one but recovering flow,”16 then the recovery of flow begins by

melting what is dammed and hardened and letting it run. In this sense, the

unification imagined by Unification Contour is

clearly distinct from the ideological unifications asserted by political powers

in North and South. They desire not flows that move toward one another, but the

absorption of the other into their own fixity.

It

is not easy to imagine unification free from the webs of suspicion, doubt,

subversion, and aversion that have clung to the word “unification” in Korean

history. If we wish for unification, we will have to reinvent it. That process,

in the end, is the imagination of a community capable of hospitality toward

those outside “linguistic, regional, familial, and national communities,”

willing to risk discord with “nonconforming beings.” The open doorway of Citizen’s

Gate, constructed from stacked container doors, appears to me as a

careful yet resolute gesture of welcome toward that as-yet-unrealized

community. In this way, art becomes a place of imagination where “if” can

be promised.

1

Michel Serres, The Legend of Angels, trans. Kyu-hyun Lee (Greenbee Life,

2008), p. 35.

2 Michel Serres, The Legend of Angels, trans. Kyu-hyun Lee (Greenbee Life,

2008), p. 15.

3 Artist interview, “ ‘The Promise of If’: A Community Bound by Sorrow,”

So-Yeon Ahn.

4 Artist interview, “Discovering the Past,” Emily McDermott, Interview

Magazine, May 2015.

5 Artist interview, “Dreaming of the Possibility of Half in the Ruins:

Installation Artist Minouk Lim,” Myung-sook Kim, Monthly Art, January

2013.

6 Ibid.

7 Artist interview, “Minouk Lim: An Adopted Incongruity Between Art and

Politics,” Hyejin Joo, Kyunghyang Article, July 2013.

8 Artist interview, “Dreaming of the Possibility of Half in the Ruins:

Installation Artist Minouk Lim,” Myung-sook Kim, Monthly Art, January

2013.

9 Artist interview, “The Belated Funeral as Performance: A Dialogue with Minouk

Lim,” Stuart Comer and Jenny Schlenzka, January

2013, http://post.at.moma.org/content_items/533-the-belated-funeral-as-performance-a-dialogue-with-minouk-lim.

10 Minouk Lim, artist’s note.

11 Artist interview, “ ‘The Promise of If’: A Community Bound by Sorrow,”

So-Yeon Ahn.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Artist interview, “Dreaming of the Possibility of Half in the Ruins:

Installation Artist Minouk Lim,” Myung-sook Kim, Monthly Art, January

2013.