1

What does art mean to Minouk Lim? Or more precisely, what is the artist doing

in the name of art? These questions arise out of the nature of the relationship

between her works and the realm of what we commonly call art: the former often

seems to go off on a tangent or sometimes far off from the latter. The artist

has intervened in the social and political reality of ‘here and now’ and

everyday life within the context of the so-called political art. In particular,

she pays particular attention to the evils and disasters brought by financial

capitalism, consumerism, new town development, bureaucracy, and individualism

which have been formed and developed under global neoliberalism, taking themes

and motifs related to them from both mass media and subculture.

Nevertheless,

unlike the older generation of political artists who used art as a

revolutionary tool for social change and the materialization of ideology, Lim

not only pursues the aestheticization of political art through artistic

imagination and creativity power but also internalizes criticism and attack on

the contradictions of modern culture, social discords, a sense of historical

loss, lost memories, and human alienation with the continuing spirit of

skepticism and self-reflection.

Above all things, she approaches the most

controversial issues such as race, gender, body, representation, identity,

subjectivity, the Other, and multi-culture with an altruistic concern and eye.

Her exclamation of grief, “what should I do to live in your life?” — 2 is, in this

sense, an expression of her hope for the mutual benefit- and

relationship-oriented solidarity with others and the embracement of

disenfranchised people. If Lim ever has something that can be called the will

to depoliticization, it is motivated by her poetic sentiment to give artistic

form to the critical attitude toward politics and society and her feeling of

healing which aspires to bridge the social separation and isolation.

In

some respect, this will to depoliticization also parallels a dual or ambivalent

aesthetics which destroys or stands on the boundary between art and politics,

public and personal histories, society and individual, subject and object,

intelligence and sensitivity, and highbrow and lowbrow. It is a practical

ambivalence which definitely refuses to fall into a mere conceptual play or the

trap of ambiguity, but rather, is charged with the willingness for openness and

change, based on the Other-oriented point of view and concrete clarity. It is a

kind of weapon with which the artist challenges the unitariness, wholeness and

singleness of modernism and strikes a blow against the paternal discourse which

created the myth of success on the basis of developmentalism.

Apart

from these anti-modernist and anti-paternal implications, her ambivalent

aesthetics is also marked by non-visible tactility and non-fixed liquidity in

style. Within the framework of feminist criticism, tactility and liquidity are

feminine qualities which are opposed to visuality and fixedness and by direct

extension, to modernist masculinity. As if to reinforce the French Neo-feminist

argument that writing in mother’s milk, or white ink (Hélène Cixous) or an

erotic style that is tactile, fluid, and “already two―but not divisible into

one(s)” (Luce Irigaray) has an explosive power to overshadow or overthrow the

masculine mode— 3, it is in this fluid/tactile style that Lim finds the

creative inspiration to dissolve social and human conflicts. Soft and active

liquid, rather than hard and inactive solid, and tactile contact, rather than

scopic distance, are the reservoir to preserve the recuperative energy to

replenish the warmth of human life.

The

fluid/tactile style is non-systemic and non-visible like the pre-grammatical

language of the Imaginary. This pristine mode, which is not contaminated by the

paternal language, breaks out of the yoke of the rules and principles of the

symbolic. Lim’s signature formal strategies such as ‘jumping’ utterances and

the rhetoric of omission and leap are the most appropriate for constructing the

style. Here, in that her ambivalent aesthetics, fluid/tactile style,

non-systemic language, the rhetoric of omission and leap, etc. are at the

antipodes of modernism, masculinity and the Symbolic, it seems to be not only

possible but also necessary to understand her art in terms of gender politics.

However, this possibility and necessity is immediately blockaded by the nature

of ambivalent aesthetics which denies a single unitary one or univocality. What

lies at the center of her art, which continually strives to remain on border,

is the act of oscillating between two extremes such as femininity and

transcendental femininity, gendered and de-gendered, constantly frustrating

determinism.

2

Ambivalence, fluidity and tactility are also the properties of the medium of

video. Video images retain non-fixed fluidity caused by the flow of electronic

particles as well as a mosaic texture which involves both two- and three-

dimensions due to the intervention of time. Besides, her editing techniques of

omission and jumping create a non-systemic and non-visual video language. In

this sense, it is no coincident that she has used video as her main medium

since 2005.

Her

video works are documentaries. But these are not about the natural world or

specific events, but records of staged performances. They are sometimes

‘narrative documentaries’ with narrative structures and other times ‘poetic

documentaries’ brimming with poetic sentiment. As is suggested by the

adjectives such as ‘narrative’ or ‘poetic,’ her documentaries leave a deep and

ingenuous impression, while always dealing with a series of pairs of

contradictories: subject and object, public and private matters, history and

autobiography, and reality and fabrication.

The

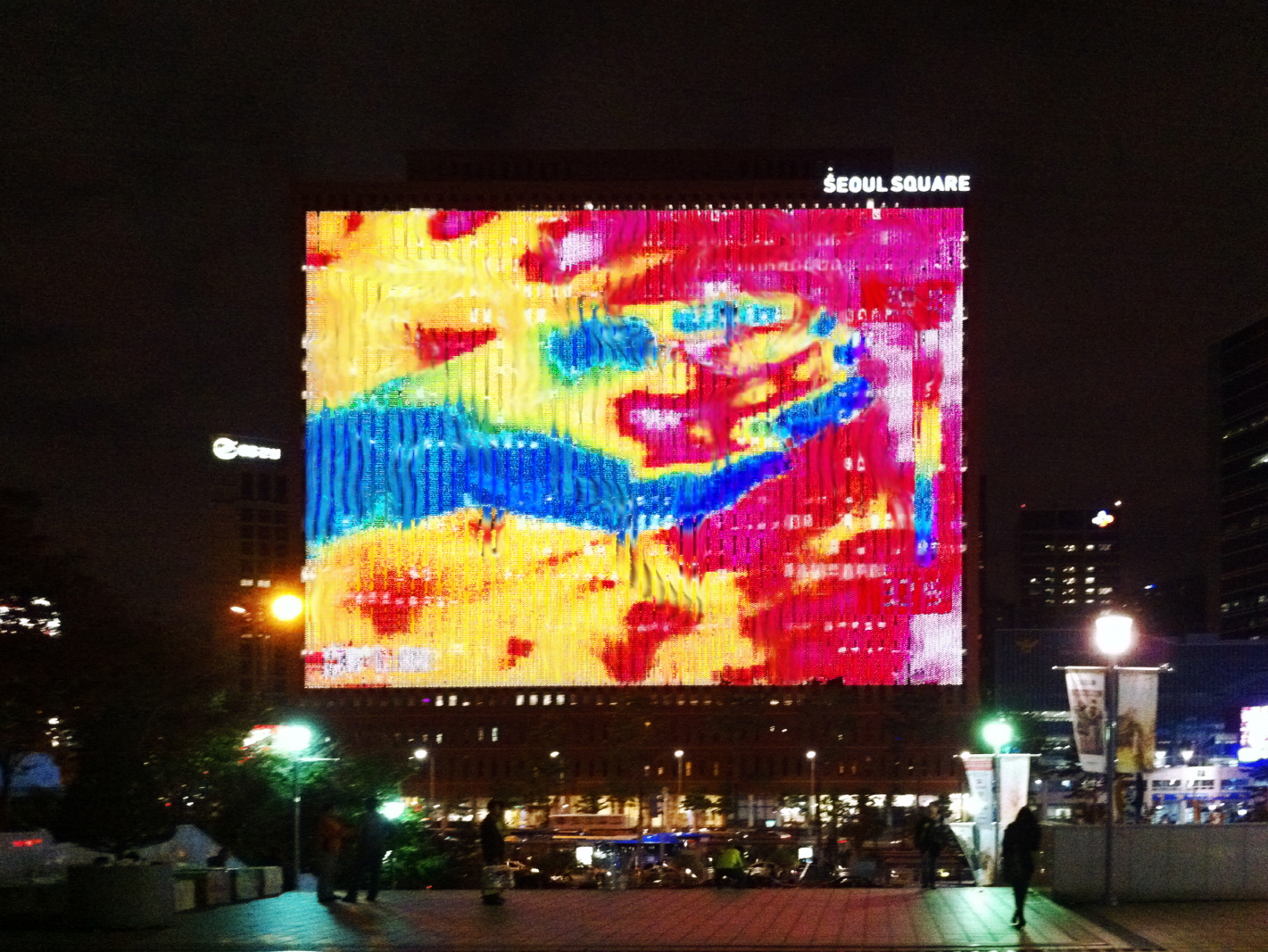

artist’s style is most vividly shown in The Weight of Hands (2010),

a documentary film which follows the conventions of the road-movie format. As

if carrying out an exorcising ritual on soon disappearing landscapes of

oblivion, destroyed and forbidden places, or spaces which are, as the artist

puts it, “already too late,” a person, beating a drum, makes a pilgrimage to

the closed ferry terminal at the foot of the cliff of Mt. Jeoldu, Seoul, the

vacant area of constructed-but-unsold housing units in Paju, and the Ipo Weir,

Yeoju, located on the basin of the Han River and laid bare by developmentalism,

etc. This pilgrimage is joined by a group of people who get off a tour bus and

begin to march in the dark. They all wear raincoats. The stream of movement

continues even in the bus: a woman who, holding a microphone, sobbingly sings a

song of farewell, is being lifted and carried by hand by the passengers. Lying

down like a dead body, or alluding to a funeral procession, she mournfully

flows through their hands like a river, like rainwater, or like tears.

The

images like nightly rain, a running tour bus, pilgrimages of a drummer and

tourists, and the lateral drift of a singing woman have liquid qualities,

symbolic of the process and energy of movement, current and mobility.

Furthermore, the artist imbues these damp liquid-like images with warmth and

heat by using an infrared thermal camera. As soon as heat or temperature

captures an object, its image goes into the ‘warming’ or ‘heating’ mode,

quickly losing the sense of substantiality and being converted to illusionary,

immaterial one. These melting, distorted forms and their translucent

colors―reminiscent of watercolors― not only contribute to enhancing the

fluidity effect but also evoke the tactile sense, inviting viewers to touch

them.

While

video images by definition have a mosaic texture, Lim’s use of thermography

maximizes their tactility by transferring realistic forms into abstract colors

and textures. Thus, the title, the “weight of hands,” could be interpreted to

mean the heaviness perceived not by eyes but by hands. As the artist suggests a

new terminology of “sight touching” for “sightseeing”— 4, she aims to recover

the spectacular scenes, which were all built upon deadly destruction, through

contacting and touching. So, instead of the hand of construction, she

introduces another one, that is, the hand of ethics whose weight in no way

measurable. If the gigantic excavators frequently appearing in her videos

represent the hand of destruction for construction, the hands of the passengers

who hold up the weak and feeble woman and try to ease her grief are those of

salvation and healing. The striking distance between these two hands which

could be respectively regarded as paternal and maternal explains the sensory

difference between sight and touch and the perceptive difference between visual

and tactile sightseeings.

—

1 The title is borrowed from Jacque Derrida’s “Living On/Border Lines”

(translated by James Hulbert, in Deconstructionism and Criticism, edited by

Harold Bloom et al., New York: Seabury Press, 1979, pp. 75-176).

— 2 Works, www.minouklim.com

— 3 Chris Weeden, Feminist Practice and Poststructuralist Theory, Oxford: Basil

Blackwell, 1987, pp. 65-68; Luce Irigaray, This Sex Which is Not One (1977),

translated by Catherine Porter with Carolyn Burke, Cornell University Press,

Ithaca and New York, 1985, p. 78.

— 4 “Here, the term ‘Sightseeing’ is replaced by ‘Sight Touching’ and the video

record of the performance becomes a medium to perceive temperature and

weight.”(Works, www.minouklim.com)

3

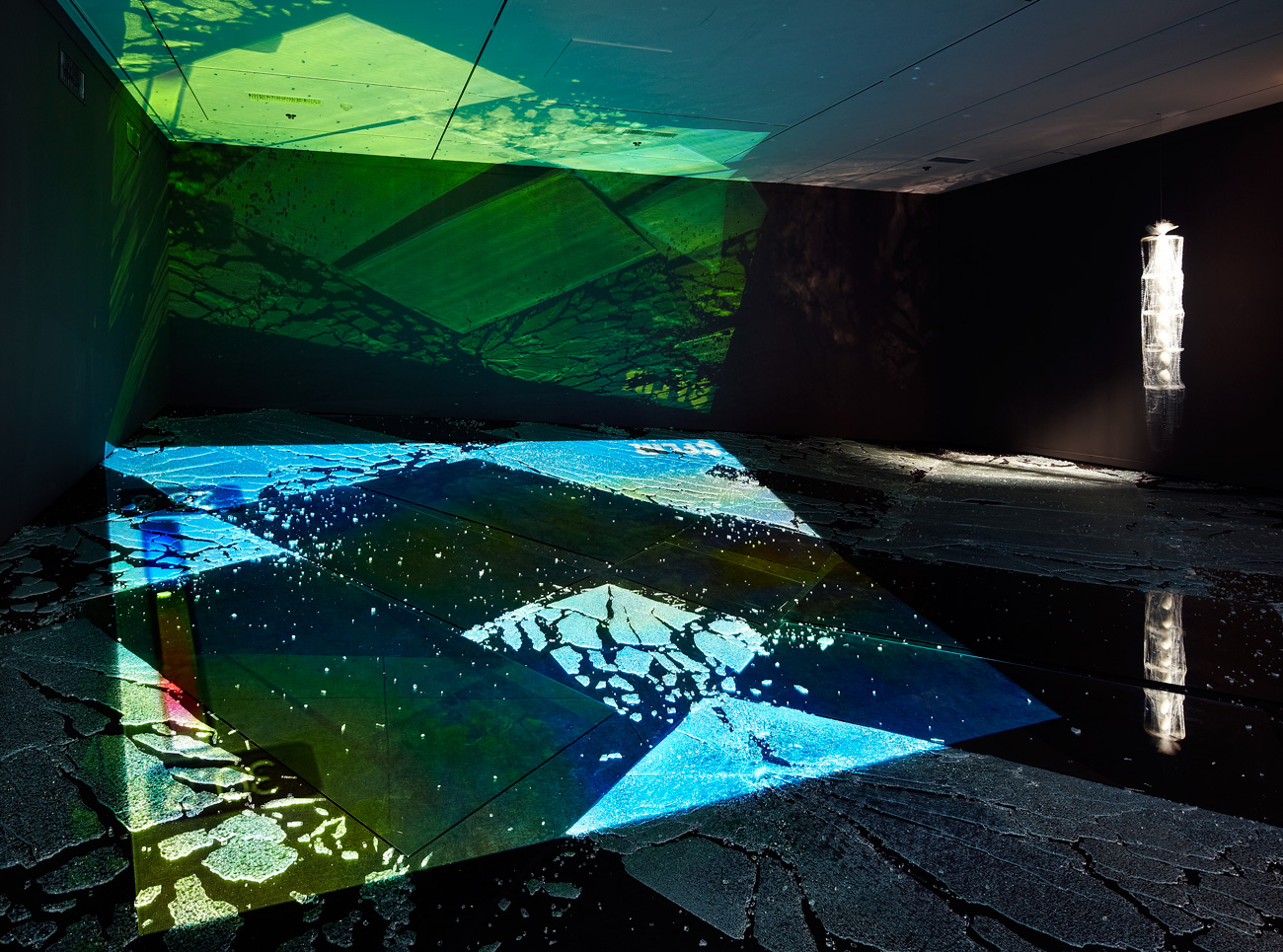

In S.O.S.– Adoptive Dissensus (2009), a documentary video of

a participatory performance given on a cruise ship along the Han River, Lim

explores the transition from visual sightseeing to tactile one. Here,

passengers on the ship are invited as the audience of the three episodes which

are being played on the riverbank. Like a story-within-a story, the film

comprises three inner narratives within a frame of cruise tour, with which it

unfolds a multilateral outer story, “S.O.S.” The artist poses questions to the

viewers by adopting three episodes regarding on the following issues: the

temporal and spatial disagreement with the ever accelerating world, the

dissensions occurring within the developmentalist desire, and the memories of

and resistances against “what we have already seen and what we have already

lost.” The audience becomes a momentary community who shares the situations and

memories of the three episodes and thereby “experiences a Möbius loop where the

role of object and subject is reversed.” — 5

The

first episode is a united demonstration of young people who rise against

developmentalism and call for “nameless places,” the second is a dramatic

farewell ceremony of two lovers who are reclaiming their refuge for love, and

the third is a lonely monologue of an unconverted long-term prisoner. All of

them send S.O.S. messages with a mirror, or by making a gesture, or through a

walkie-talkie, but the ship’s searchlight does not answer them, only to scan

the facade of the city. Though a real S.O.S. rescue did not take place

actually, the artist’s questioning about the “Han River Renaissance” leaves a

long-lasting impression both to the passengers on the cruise and to the viewers

in the exhibition room.

Here

again, as might be expected from the fact that it was a waterborne performance,

aquatic images and the motif of movement remain prevalent. All the passengers,

let alone the ship itself, join in movement and the light of the searchlight

and the synchronous sound heighten the excitement and tension of the cruise. If

the sensations of liquid and movement are evoked by tactile images in The

Weight of Hands, it is an omnidirectional, multisensory environment

that creates the same sensations in S.O.S. Adoptive Dissensus.

The artist becomes both a writer and director of this environmental total

theater, actors and audience being the Han River, the lifeline of Seoul, the

cruise ship, the captain and passengers on board, and the performers of the

three episodes on the three sites on the riverbank. This kind of a large-scale

collective performance which occurs real-time in a specific place for two days

inevitably emphasizes the sense of community and cooperation rather than an

individual’s vision, as well as involves the elements of life marked by its

accidents and events. Ultimately, by advocating life art and popular aesthetics

and attempting to unify the irreconcilable discordances such as art and life,

or art and the public, the artist proposes another Möbius loop in another

level.

As

was shown in the two above-mentioned works, rainwater and river water are the

symbolic subjects and motifs to embody the artist’s fluid/tactile style.

Furthermore, water has also an important meaning as an artistic material. This

liquid medium to dissolve heterogeneous substances into one inspired her to

find a new mixing technique of ‘marbling,’ i.e. a formal hybrid of unexpected

patterns and textures created by arbitrary blending of water and pigments. As a

visual expression of the liquid non-fixedness and as a product of the momentary

contact which brings disharmony into harmony, marbling serves as a key

technique in her unique style.

On

a rainy day, Lim had an extreme marbling performance in which she poured paints

on the car roof and then drove speedily so that they could melt in rainwater.

Or she built an imaginary miniature New Hometown by sticking

bundles of useless pens and pencils into a marbling canvas which she had made

by dissolving paints in water in a pool. The driving performance on a rainy day

and the site-specific installation in a pool were open to public as the formats

of documentary photography and ink-jet prints as part of To No Longer

Tell the End of the Rainy Season (2008). Here, she bitterly denounces

superfluity and excess, unlimited desire for growth, and the ideology of rapid

development, all of which are suggested by the rainy season or a flood on the

one hand, and on the other, earnestly prays for the communication, connection,

and harmonization between the self and others through the marbling technique of

mixing heterogeneities.

Considering

the fact that marbling allows the joining between art and external

nature/natural phenomena, latex, Lim’s another favored medium, can be used to

the same purpose. She pours liquid latex onto the roof of buildings or the

ground and exposed it to sunlight, wind, snow and rain for several months,

until it is hardened. This too is a fluid/tactile work to produce specific

textures by solidifying liquid. So both marbling and latex work are the

indexical trace of natural phenomena as a product of physical contacts. In

index art forms such as photography and video in which the image is identical

with its subject, physical marks are presented instead of imitative

representations. Therefore, Lim’s narrative/poetic documentary films which

recorded redevelopment districts, the “already-too-late” spaces requiring

memory, their trails of destruction and the process of reconstruction with her

unique fluid/tactile sensibility rather than with her eyes, are an extension of

her marbling and latex works based on the same sentiment and imagination.

—

5 Minouk Lim, S.O.S – Adoptive Dissensus — Bartleby in Myself (2009),

exhibition catalog of Hermès Foundation Missulsang 2009, p. 154.

4

Portable Keeper (2009) and New Town Ghost

(2005) are documentary videos of the performances given in the redevelopment

district in Yeongdeungpo, Seoul. In Portable Keeper, a

young man carrying on the shoulder a bar-like strange object made of tying

together useless writing utensils, bird’s feathers, faux fur, and fan wings

strays aimlessly through the market site and urban areas which became ruined or

changed to construction fields under the influence of The New Town project. The

thing on his shoulder reminds you of a weapon or an incantatory object but he

just looks enervated and exhausted, far from being a warrior or a shaman. The

object with which you can do nothing and which is useless and functionless and

its keeper seem to represent the sigh of grief over and the resignation to the

irrecoverably “too-late space.”

In

New Town Ghost, a street band composed of a rapper and a

drummer sing the resistance against and surrender to developmentalism in the

back of an open truck, their moving stage, traveling around the bustling

Yeongdeungpo Market. The female rapper in short cut hair recites aloud the

artist’s sarcastic texts about construction, prosperity, and the progress

ideology, announcing the advent of the sheer ghost of uncompassionate

developmentalism. The performance which is suggestive of an MV of an indie band

or a boisterous election campaign was done, moving around the neighboring area

of the artist’s home and office. In contrast to the ruined scenery which will

be selected as the setting for Portable Keeper after four

years, the area is still shown as the space of everyday life, crowded with

signs, stores and passersby.

Through

these two site-specific videos which include the recollections of her own and

her neighbors, the artist deals with the process of redevelopment of

Yeongdeungpo changing from the city’s old center of manufacturing to the

present new town and the complex feelings of its inhabitants’ hopes, regrets,

resistance and accommodations. If the clamorous rapper anticipates the specter

of development, the silent portable keeper intends to hand down the lost memory

as the last witness of the old town.

As

is illustrated by the way in which both of the two films closely interweave the

history of Korean redevelopment with the artist’s own story, Lim’s works

largely start from her personal and everyday experiences. Similarly, Game

of 20 Questions: the Sound of Monsoon Goblin Crossing a Shallow Stream,

a documentary of “The 4th Migrants’ Arirang 2008” shoot and edited by her, does

not avoid autobiographical reference. As if to confirm the feminist slogan “the

personal is political,” the artist investigates the truth and falseness of the

discourse on multiculturalism, in particular, the racial problems inherent in

the designation “Kosian” from the viewpoint of the minority family with a

French-Korean daughter, turning an altruistic eye toward and facing up to the

emergence of multicultural family as a new social phenomenon and a new

community in Korea today in the global age.

Wrong

Question (2006), the 2 channel video work, presents the familiar

urban images like construction fields, demonstrations, and expressways,

accompanied by the ‘voice-over’ narration of a taxi driver who is emphatically

praising the rapid economic development occurred under the Park Jung-hee

regime. These scenes are interrupted frequently by scenes showing the artist’s

daughter –who appeared also in Game of 20 Questions – asking

questions in Korean to her grandfather. By using voice-over technique to create

the incongruity between image and sound, Lim tells you that the right answer to

a wrong question lies “not in the correspondence between image and sound but in

what is left behind in their distance.” — 6 In other words, the solution can be

given only by the attitude of mutual benefit which acknowledges difference, not

by binary oppositions such as left/right, new/old, east/west, which eventually

come down to agreement and identification. This is the very role of imagination

which is different from ideology and simultaneously, the power of art which

varies from politics.

—

6 Works, www.minouklim.com

5

In her Hermès Foundation Missulsang exhibition in 2007, 《Too Early or Too Late Atelier》, Lim aims to

show how imagination and art overcome ideology and politics and accept

diversity and difference. If a series of installation works including a latex

carpet made by casting the ground, a quilted car cover hanging from the

ceiling, and a transformed refrigerator are personal responses to the modern

urban life and everyday experiences, the video work titled The First

Impression of the Second Edition underscores the potentiality of the

present progressive tense which can be a new start at any time through a

bookbinder working in Choongmuro who concludes everything by saying “my name is

~ing.” The meaning of ‘too early or too late atelier’ might lie in opening

“polymorphous and complicated worlds in the distorted relation with the past

and to find another possibility of practice in them.” — 7

Original

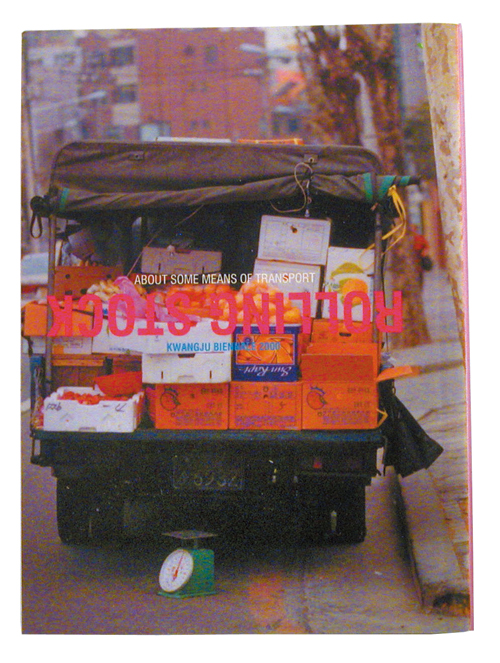

Live Club – Women’s Only Space presented in 2006 Gwangju Biennale

brings up a self-regulating alternative to globalism as a paternal structure

and the institutionalized biennale. At the entrance of this women’s only space

are screened the female images circulated in male entertainment establishments

and in the inside where both economic and porn magazines are supplied, female

audience are encouraged to take copies of their body parts as a participatory

activity. In the process in which the secret stories about what is going inside

are conveyed to male audience only through female participants’ explanation,

the female sex is mystified and information is distorted or omitted. By

creating a gender-specific space, Lim subverts the hierarchy of the traditional

art institution, exhibition culture, audience’s attitude, and the order of

communication. If this piece is conceived to “find another possibility of

practice” for the “distorted” biennale, it might be appropriate to rename it

“too late or too early Gwangju Biennale.”

The

exhibition 《Jump Cut》 held in Artsonje Center, 2008, shows not the tragedy of time

difference, which is ‘too early or too late,’ but another kind of movement

found in improvisation, accidental encounters and temporary relations.— 8 Here,

the movement relates to marbling using water, rain, flow, and natural

phenomena, that is, the casual action caused by momentary contacts between or

among heterogeneous elements. The artist moved the old-type Hyundai Grandeur,

the car she drove herself in a rainy day for her marbling performance, into the

exhibition space and converted it to a fountain called The Miracle of the Han

River. By liquefying and nullifying the miracle and a Grandeur, the Korean

symbol of prosperity, authority, riches and honors, into the monument of water,

she satirizes the distorted too-early-or-too-late Han River Renaissance.

The

eponymous work of the exhibition was Andrei Tarkovsky

‘Offret-Sacrificatio’―Jump Cut (2008), a film which attracted much

attention from the audience. Instead of taking the documentary format, this

eight-minute-long single channel video is a concise edition, or to use a

technical term, a jump-cut version of the feature film, The Sacrifice

by Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky. Because of its rapid scene changes, the

original storyline was impaired but the viewers were made to use their association

and imagination freely and actively. The artist gave back the edited, cut, or

omitted parts, which had been sacrificed in the process of making the new

version, as the audience’s share. However, this mode of interactive

appreciation which requires the recipients’ participation is also what she

demands from her own work created in a non-visible and non-systemic language

like jump-cut, that is, the rhetoric of omission and leap. By sacrificing the

film by the master director of the century using the jump-cut technique, she

attempts to recall the victims of the growing pains of the too-early-or-to-late

modernization to the audience and make them think over the true meaning of the

sacrifice for the salvation of the world and the development of the human race.

— 7 Works, www.minouklim.com

— 8 Works, www.minouklim.com

6

Her jump-cut version made the original film, which is well-known for being

difficult to understand, much more difficult. Perhaps it might be that the

artist intentionally chose the jump-cut technique to make it speak for her

difficult art and its validity. Lim’s videos marked by ambivalent aesthetics, a

fluid/tactile style, and a non-systemic/non-visual language have much in common

with the films by cine-artist Tarkovsky who denied realism, popular tastes, and

commercialism in pursuit of art cinema, but nevertheless, still persisted in

intertextual film-making for the audience. Besides, Lim’s critical concerns

about politics, society, culture, gender and ethics and practical activism are

also in line with the thoughts of the cine-artist who opposed authority from

critical and democratic viewpoints and talked about the future hope which would

be made possible by the memories of the past, nostalgia, and sacrifice with

constant self-examination and enduring humanity.

Lim’s

critical attitude and activism were evident in her early career. After

graduating from École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris, in 1995, she

worked as a member of a radical artists’ group “general genius” which she

organized with seven artists including Frédéric Michon in 1997, and then, had a

lot of exhibitions from 1998 when she returned home to 2001 when went back to

Paris. In defiance of the museum culture or exhibition conventions, most of her

works in this period were enterprising and alternative projects which replaced

object-oriented exhibition with process-oriented field work, making exhibitions

themselves the works of art. Social Meat (1999) presented in

the group exhibition “Tendencies of the New Generation” at ARKO Art Center

caused a great sensation and earned her ‘enfant terrible,’ for it realized the

provocative idea of opening the museum store as an exhibition room or changing

the exhibition hall to a rabbit warren.

After

coming back to Seoul again in 2004, Lim formed Pidgin Collective as a

descendant of Pidgin Girok (or Pidgin Record), an artists’ group in which she

had worked with Frédéric Michon since 2000, pursuing alternative activism in a

more earnest way. As she articulated the goal of Pidgin Collective as “not to

be limited to the single domain of the art world, but to create new situations

to disturb situations inside society,”— 9 or as term ‘pidgin’ suggests, the

collective prefers cooperation and community, having executed a lot of

non-systemic, temporary, process-centered and open-end projects. This is why

the group has paid more attention to everydayness and subculture than artistic

purity and attempted to draw out communicative, participatory, and interactive

creativity from them. The series of Scrap Project, performed in cooperation

with the Haja Center, a Korean alternative school, from 2004 to 2006, provided

an active archive with which to create a new art movement group involving in

the political and social reality and to develop a new model for youth culture.

The

art world of Lim who criticizes about the political and social contradictions

in contemporary Korean society in broad terms and more narrowly, new town

development, and sometimes the art institution, trying to present recuperative

alternatives to them, takes root in the aesthetic foundation which is made by

tempering and refining her keenly critical mind toward political issues and

interventional activism with artistic creativity, humanistic reflection and

literary sensibility. Standing at the frontier zone between politics and

aesthetics, armed with intelligent suspicion, ethical hesitation and the

sensibility of jump-cut-like omission, the artist constantly withholds any form

of political creed and assertive utterance which is all too subject to be declarative

and educative.

As if being the double of Bartleby, the eponymous main character

in Bartleby, the Scrivener by Herman Melville, like a

Bartleby here and now who tries to “read the invisible from what they see and

see something from the invisible,” Lim belongs to “those who hesitate and keep

looking back questioning themselves rather than giving a confident answer of

yes or no” and converts her resistance and negation to the rhetoric of

“momentary tremors, hesitations, empty talks and murmurs.”— 10 And this is

exactly where both the portrait of Lim, the artist living on border, and her

art found on ambivalent, borderless aesthetic are now placed.

—

9 Youngwook Lee, “Fine art, Too Late or Too Early,” Jump Cut, exhibition

catalog, Artsonje Center, 2008. p, 89.

— 10 Minouk Lim, “S.O.S. – Adoptive Dissensus―Bartleby in Myself.”