1. Testimony to Say ability

Minouk

Lim is interested in that which is invisible. However, this does not mean her

intention is to dismiss the visible and reinstate what is not. In other words,

she does not adopt anti-representationalism, but instead attempts to ‘testify’

on behalf of what is invisible. This method is of considerable interest, since

it appears as though what she intends to achieve is to pass beyond the

arrangement of images in order to materialize ‘sayability.’ Such an interest in

sayability is the thematic consciousness that runs through Lim’s entire oeuvre.

Therefore,

what is important to Lim is ‘speaking.’ Her artworks consist of spoken words.

They are sometimes stories, at other times incomprehensible mutterings, and at

yet further times they appear as ear-splitting noises. As such, spoken words to

Lim are invariable sounds. Sayability premises that some things are unsayable.

That which is unsayable does not exist. Lim strives to take such things that

are supposed to be nonexistent and makes them exist. How is this possible?

According

to Giorgio Agamben(1942-)’s definition, ‘sayability’ is ‘the thing itself.’

Agamben states the following:

“The

thing itself is not a thing—it is the very sayability, the very opening which

is in question in language, which is language, and which in language we

constantly presuppose and forget, perhaps because the thing itself is, in its

intimacy, nothing more than forgetfulness and self-abandonment.”1

What

is noteworthy in Agamben’s quote is that sayability is in apposition to

‘opening,’ as is ‘forgetfulness’ to ‘self-abandonment.’ At first, things are

what can be expressed through language, but the moment they are rendered into

words, they are excluded from language. For this reason, the thing itself is

forgotten and consequently abandoned. What Lim’s art illustrates is this

lingual exclusion itself. Speaking calls attention to the existence of the very

thing thusly excluded.

Sayability

is therefore the fundamental unit of existence. This is because if something is

sayable, testimony can be given to its existence even if it cannot be seen.

Collecting such testimonies composes the core of Lim’s work. As Walter

Benjamin(1892-1940) once said,

“The translation of the language of things into

that of man is not only a translation of the mute into the sonic; it is also a

translation of the nameless into name”2

As in the act of

translation to which Benjamin refers, restoring those things excluded by human

language back into the realm of language is exactly the underlying

philosophical motive that can be discovered in Lim’s work. Following the

precedent of Goethe(1749-1832), Benjamin defines works of art as ruins. To

Benjamin, a text is similar to a ruin that offers testimony to an Ur-text that

is no longer visible but had once surely existed. For this reason, the text of

ruins can in fact be referred to as a testimony.

A

thing itself is sayable because, without language, nothing can be communicated.

In the end, even miscommunication is possible only through the medium of

language. Therefore, misunderstandings arise regarding the things themselves.

There are inevitable misunderstandings that arise from expressing the unsayable

in words. In a way, this indicates that what has not been said is included in

what has been said. In this context, sayability stems from the fragile medium

of language, and this is what forms Lim’s perspective on communication.

2. Stories: Subjectification without the Subject

Doubting

communication is an important issue for Minouk Lim. Her insight into the

fragility of language is evidenced in Game of 20 Questions—‘The

Sound of a Monsoon Goblin Crossing a Shallow Stream’ (2008)

(henceforth Game of 20 Questions) and S.O.S.—Adoptive

Dissensus (2009) (henceforth S.O.S). These two works deal with

the idea of being able to freely express one’s thoughts and of being unable to

say ‘no’. In Game of 20 Questions, words are fragmented

into noise and devolve into a repetitive rhythm. The divided screen depicts the

same space, but the words being sounded are of varying dimensions.

Here,

the signifiers of multiple cultures acquire specific personalities. The

characters are the signifiers. These signifiers are spoken entities, but also

include what is not verbalized. This is why Game of 20 Questions seeks

to uncover something to say, as if in a game. In Wrong Questions (2006),

a work that deals with an agent excluded from language, a taxi driver who

launches into an extended monologue has nothing at all to do with what he is

saying. His words have been predetermined for him. Even the content is not

about him, but about Korea. Here, what is being testified in this work is how

words from a nation ultimately excludes and isolates the taxi driver.

Wandering

about in search of a place to park, or to stay, is a citizen who longs to claim

his or her own space. That is calling this citizen is the ideology that is

being ‘testified’ through the taxi driver’s vocalization. However, there is no

specific place for this citizen to reside. The taxi moves, and its location

expands into the abstract space of a nation. Wrong Questions is

an intriguing work that demonstrates how ideology speaks.

Lim

appears to believe that what is important is less the elimination of ideology

than making known the fact that an ideology is present. That is why, rather

than arguing in favor of a post-ideological era, she opts to describe a story

within an ideology. What she deems important is the storyteller. One might

wonder why stories and storyteller are important. Why stories and the

storyteller? Lim seems to regard stories from a similar perspective of

Benjamin, who stated the following:

“The

storytelling that thrives for a long time in the milieu of work—rural,

maritime, and then urban—is itself an artisanal form of communication, as it

were. It does not aim to convey the pure “in itself” or gist of a thing, like

information or a report. It submerges the thing into the life of the

storyteller, in order to bring it out of him again. Thus, traces of the

storyteller cling to a story the way the handprints of the potter cling to a

clay vessel.”3

Lim

pursues the traces of a storyteller, which are like the handprints of a potter

clinging to a clay vessel. What Lim offers in order to overcome reality

in Wrong Questions is FireCliff

2_Seoul (2011), a performance in which a storyteller relates his

experience of torture in the form of a story. The staging of an experience is

perhaps the fundamental principle behind stories. FireCliff

2_Seoul does not simply accuse, nor merely report the facts of

torture. By inviting the victim of torture on to the stage, Lim converts him

into a storyteller. Of course, this characteristic is also evident in FireCliff

1_Madred (2010), through which the experience of working at a

factory in Madrid is delivered through the alternative forms of stories and

songs, completing an ‘artistic form of communication.’

This

method is put to the greatest effect in International Calling

Frequency (2011). As discussed above, Lim completely excludes

the traditional form of language itself in this work. Of course, such exclusion

does not indicate the elimination of language. However, by refusing to

designate any one particular language, Lim attempts to unravel the individual

held captive by her own identity. Those humming the tune are indeed distinct

individuals, but they also constitute a network converted into a single

international calling frequency. In this work, Lim’s story reaches the level of

poetry. Of course, the resulting poem does not share the sensitivities of

conventional lyrical verse. The poem is instead more approximate to what Alain

Badiou (1937-) calls the ‘matheme of the event.’

Poetry

offers testimony to the production of truth and secures that truth through

being put into text. The poetic agent born through this process is the very

agent of the truth that constitutes ontology. To Badiou, truth is an expression

of the abyss. This abyss of existence is nothing but nothingness. Nothingness

is a nonexistent cause, and in the end it is the traces of this absent cause

that constitutes poetry. Therefore, poetry is invariably an example

demonstrating the preceding absent causes. In other words, the poetic text is

an expression of an event that occurs prior to the subject’s becoming. An

absent cause does not exist, thus constitutes the paradox of an event. Badiou

asserts the following:

“The

paradox of an eventual-site is that it can only be recognized on the basis of

what it does not present in the situation in which it is presented. Indeed, it

is only due to it forming-one from multiples which are inexistent in the

situation that a multiple is singular, thus subtracted from the state.”4

What

makes this paradox of an event possible is the core of reality and truth. Like

Jacques Lacan (1901-1981)’s notion of fantasy, the paradox of an event is a

seduction in the direction of truth but simultaneously the cause of maintaining

a certain distance from the truth. To Badiou, the relationship between truth

and subject is composed by the axiom of infinity. As such, at the core of

reality is emptiness. Badiou’s method is to name this empty core the void. Then

what is void? According to Badiou, void is that which is excluded from an event

that has settled as a situation. In plain language, events can be categorized

into situations and states, where a state is a permanent rendition of a

situation. That is, situation minus void equals state. In this context, an

event never has any choice but to remain a ruin.

3. The Flâneur at the Ruin

The

ruins that appear in the works of Minouk Lim are traces of events. What Lim

works to show is a situation in which an event has been reduced to state. The

sentiment of anger emanating from New Town Ghost (2005)

later appears to have acquired a further dimension in Portable

Keeper (2009). The man toting the ‘keeper’ all over a

construction site looks like a parody of the flâneur, or stroller, who wanders

about in the city making roundabout tours. Labeling a painter named Constantine

Guys as a flâneur, Charles Baudelaire claimed that Guys was an artist who

embodies a certain quality that can only be referred to as modernity.

Baudelaire’s image of ‘flâneur’ overlaps to a certain degree with that of the

man in Portable Keeper. Regarding the flâneur, Baudelaire made the following

statement:

“The

crowd is his element, as the air is that of birds and water of fishes. His

passion and his profession are to become one flesh with the crowd. For the

perfect flâneur, for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up

house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the

midst of the fugitive and the infinite.”5

Baudelaire

is indicating that taking leisurely strolls in the city streets is a

characteristic of modern art, or of modern poet. Of course, this sort of stroll

is without a point of destination and is different from what is commonly called

a ‘walk’, which is taken deliberately as exercise. The stroll represents the 19th century

Parisian culture which considered turtle-like sauntering to be elegant. To

Baudelaire’s flâneur, taking a stroll is a condition for his existence, and is

closely related to the crowd. The flâneur is a person who collects plants in a

field of asphalt.

What caused the flâneur, as Baudelaire detailed, to appear in 19th century

Paris? Benjamin points to the passage, or the arcade, as what induces the

leisurely footsteps of the flâneur. The arcade was a most suitable place for

leisure strolls. It was Baudelaire who elevated the status of the flâneur from

a wandering idler looking around the arcade to that of a poet.

Baudelaire defined the flâneur as the modern poet, or in other words, as a manner

of existence for modern artists. From this definition, what is the truth that

can be read? The flâneur can indeed be considered someone who demonstrates the

evolution of artists’ mode of existence in the face of modernity. In this

respect, the flâneur is closer to a collector than to a poet for Benjamin, and

this point is what distinguishes Benjamin from Baudelaire. Benjamin viewed a

street as a place of residence for the collector. In such a site, the flâneur

of Benjamin, unlike that of Baudelaire, does not compose a poem but instead

collects something and then produces knowledge:

“That

anamnestic intoxication in which the flâneur goes about the city not only feeds

on the sensory data taking shape before his eyes but often possess itself of

abstract knowledge—indeed, of dead facts—as something experienced and lived

through. This felt knowledge travels from one person to another, especially by

word of mouth.”6

As

it is understood here, the flâneur is a producer of new knowledge as a modern

poet. However, the flâneur does not belong to the system of division of labor

evinced under Capitalism. The flâneur is more an artist than a laborer. The

flâneur endeavors to escape from the Capitalist system even though he is a

producer. Therefore, such producer is a dreaming idler who has fled this

system. If so, what knowledge does a flâneur produce? Knowledge ‘comes only in

lightning flashes’ and ‘the text is the long roll of thunder that follows.’ The

power that generates this type of knowledge is neither logical reasoning nor

rational statement, but rather shock and the Erlebnis, or experience, of a

catastrophe. In a nutshell, knowledge is a process which the fragile form of

language is exposed. The thunder that weaves the roll of text is itself the

poetic event.

However,

there is no event in Portable Keeper. The event has

already occurred, or alternatively has yet to happen. What the piece

fundamentally exhibits is a man strolling around a construction site. This man

appears to ramble at leisure, but unlike the flâneur he has no arcade to view.

Already, the building has vanished and this solitary man is simply wandering

about. In this respect, Portable Keeper becomes a

parody of Baudelaire’s flâneur. Once a beneficiary of modernity, the flâneur is

now destined to stroll around the ruins that have resulted from redevelopment

projects undertaken under the banner of modernity.

The landscape of ruins imposes a nihilist attitude upon the flâneur. However,

the ‘keeper’ grasped by this man loitering about the construction site serves

as a device to counteract modern nihilism. The keeper, as the word literally

indicates, is intended to be held in the hands with the aim of protecting

something. What on earth is this man trying to protect? At this point, Lim projects

an entirely different attitude toward what has disappeared. She is less intent

on recording what has disappeared than on preserving what is currently in the

midst of disappearing.

Each and every scene captured in her pieces is something

she aspires to safeguard. In other words, they are things that are made to

return to language. This is evident in Rolling Stock (2003).

The rapid change of scenes precisely corresponds to the rhythm of the music, as

the scenes grasp for the disappearing images. This type of repetition will

continue until an event occurs, and so will the music. In this context, the

rhythm and melody of the music serve as a temporary residence.

4. Things that Become Possible only through Impossibility

The

ruining of event is the element that renders the event’s entire formation

impossible. It seems to indicate the relationship between the symbolic and the

real as identified in the theory of Lacan. The real establishes an indivisible

relationship with the symbolic, but is never embraced as a proper member of the

symbolic. The real belongs to the realm of the unconscious, which in Laconic

terms constitutes the whole of images and language the self borrows from others

in order to complement the ‘place of privileged trauma’ known as sexuality.7 The

unconscious constitutes an individual’s uniqueness. The self signifies the

location of these peculiarities.

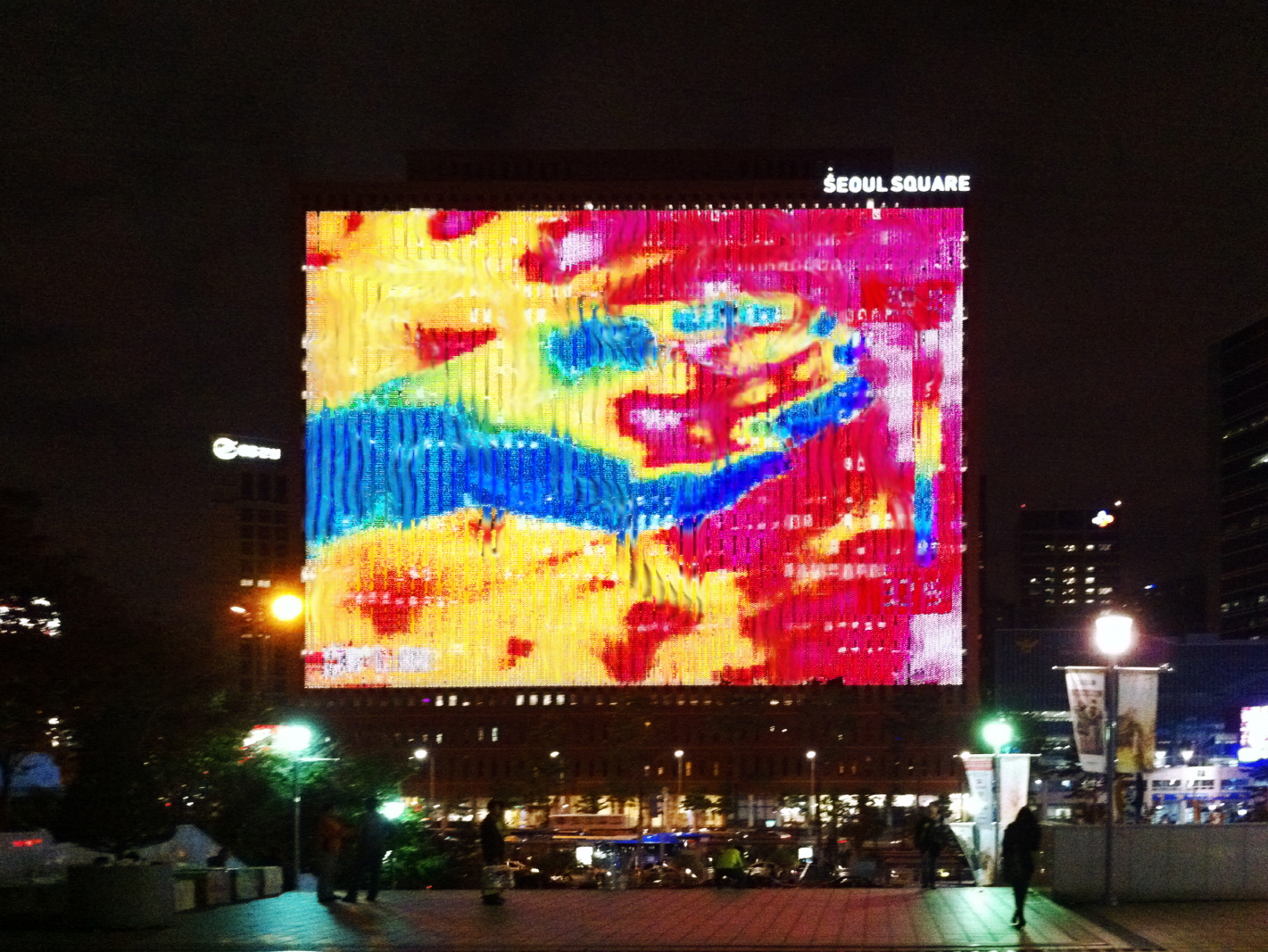

International

Calling Frequency is an important project attempting at

collectivizing this uniqueness of the agent. What is required in this task is

the agent’s devotion, calling for the agent’s desire to lend him or herself to

the international calling frequency. Badiou extracted his category of agent’s

devotion as he analyzed Stephane Mallarmé(1842-1898)’s poem Un

coup de dès jamais n’abolira le hasard. Badiou wrote, “On the basis

that ‘a cast of dice never will abolish chance,’ one must not conclude in

nihilism, in the uselessness of action8.” Here, nihilism occurs

because one clings to a ‘cult of reality’ and fails to accept ‘its swarm of

fictive relationships’ as they are. To put it another way, nihilism refers to

the despair that results from a situation in which an agent intent on pursuing

a subject does not acknowledge the fact that it is impossible to apprehend the

subject. The obsession to represent the real eventually leads to nihilism, and,

in contrast, the refusal to face it leads to one being swallowed by

quasi-imaginative images that cast shadows deep down into the abyss of

existence.

While

Badiou captures behaviors other than nihilism through Mallarmé’s poem, Lim

organizes a sequence of imaginative actions that characterizes the process of

generating truths, known as poetry or art, through her work International

Calling Frequency. Art

reorganizes the world based on a foundation that precedes the traces of the

real. This reorganization inevitably entails criticism regarding the existing

world. Therefore, art does not halt at the simple level of techne, as art

that settles for such level easily succumbs to nihilism. By reorganizing

normative conditions, however, it is possible for art to conquer nihilism. In

Jacques Ranciére(1940-)’s terms, this is to rearrange the distribution of the

sensible. Badiou’s poetic virtue of Mallarmé is to set free the sensible —

which has been divided by the community into a hierarchical order — on an

aesthetic level and then to share it in a novel manner.

What

is significant at this point is the act of reorganization. The process faces no

choice but to go through the three stages of disintegration, abolition and then

affirmation. Therefore, the act of art, which does not conclude in nihilism

according to Badiou, does not denote an anti-aesthetic performance that remains

at the phase of disintegrating the distribution of the sensible, but rather the

production of the new that arises from the aesthetic premise. What indeed is

the production of the new? It is an aesthetic dimension that incapacitates the

sharing of all senses, as well as a precedent foundation that creates traces of

an event—that is to say, a situation. Art is what fixes into text the debris of

the event that has been left into ruins after the situation has expired.

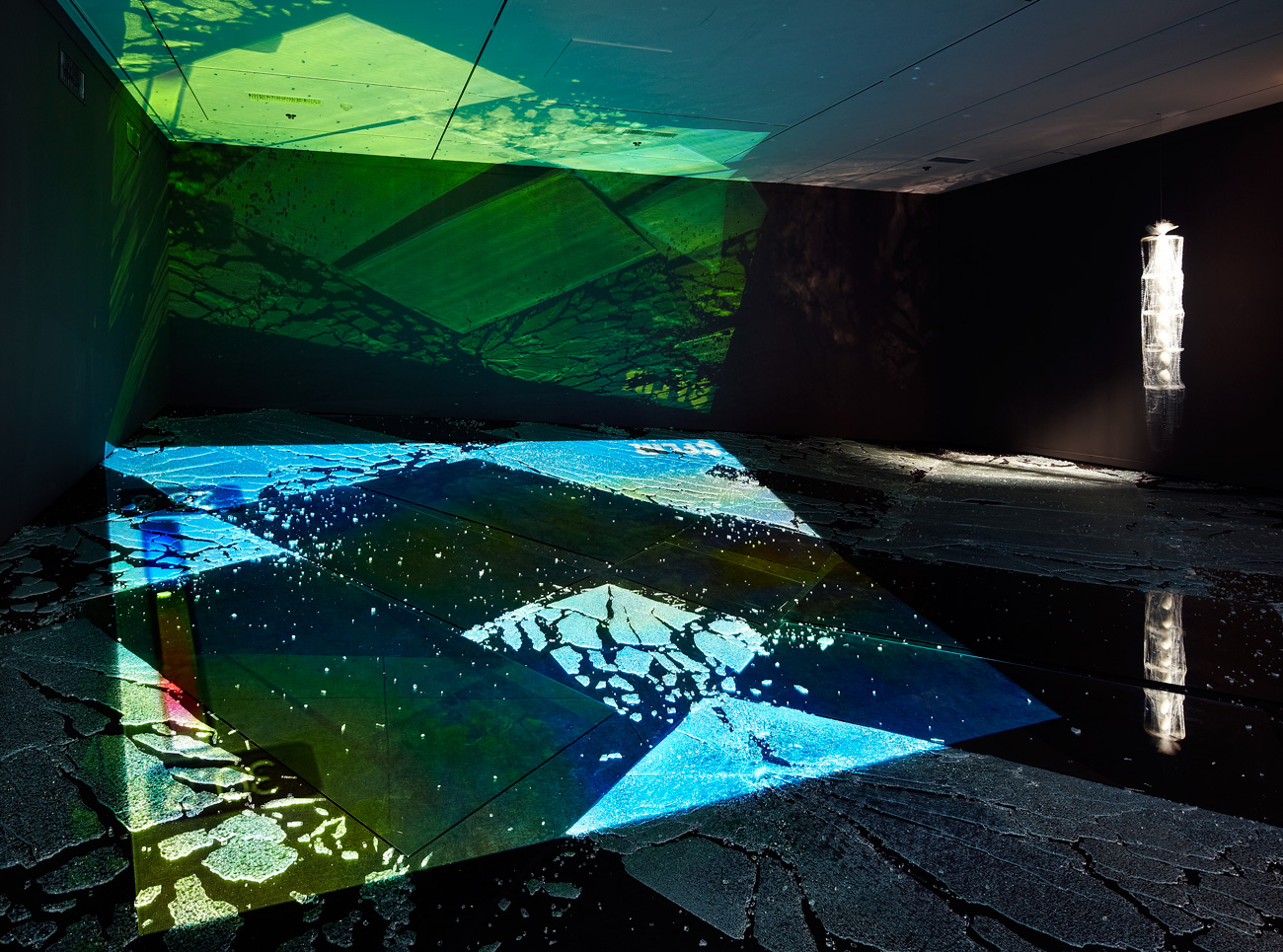

Lim’s

art intends to discover this situation within reality. It is her virtue to

summon the situation that has disappeared, leaving nothing but the ruins. This

is what the artist attempts to express in The Weight of Hands (2010).

In varying degrees of temperature through an infrared camera, the work depicts

hands which are both a product of evolution and a primary means of labor. What

the colors convey can be seen as literally the weight of hands. Viewed from the

outside, their invisible mass turns visible through temperature, demonstrating

a conversion into sensorial realm.

What

is necessary here is a transition from the negative to the positive. Lim

implies that the action against the plunging into nihilism makes this

transition possible. This action represents the devotion of the agent toward

the truth of the event. This relentless pursuit of truth, which enables an

event to have traces, is actually what Badiou refers to as the poetic spirit.

Such truths are the absent causes that generate events. The task of poetry is,

Badiou believes, to identify such truths. A complete text cannot be established

from this perspective, because what poems ultimately intend to reproduce is the

void of a situation that has already been subtracted.

A void cannot be

reproduced in text. As such, the text the artist exhibits by means of an infrared

camera is actually the irreproducible. In this manner, Lim intends to explore

ruins and present the points of truth using topology. As in the case of the

symbolic, her works enter into existence as an artwork through such

impossibility of establishment. If something like a map covered in signs and

symbols is what Badiou regards as poetry, then Lim’s art is like a map in which

colors and sound embodied in topological terms draw the contour lines.

From

such perspective, Lim’s works appear to prompt subjectivism. They might leave

an impression that the subject’s action comes before what the subject is

attempting to capture. Such doubts can be raised since the subject does not

reproduce the objective world, but rather demonstrates the accumulated

subjective projections that relate to it. This is also the case with

International Calling Frequency. One may think that this manner of performance,

which denies any organization or medium, further promotes nihilism.

The subject

in each of Lim’s work, however, is always interlocked with objective, physical

conditions that exist ‘over there.’ No matter how much the subject seeks out

its object and argues the truth, there must be preconditions that make such actions

understandable. Lim’s works constantly presuppose such conditions, which may

explain the frequent appearance of reconstruction sites or sit-in strikes in

her works.

Lim’s

works always have a sense of concrete placeness. Of course, this placeness is

not fixed, but has the tendency to be fluid. Lim’s interest lies on the fluid

placeness, or the space of mobility. In order for the subject to establish a

relationship with things, a cognitive framework should be in order. This is

what Badiou regarded as the law of techne. The function in Techne is quite

empirical. For example, techne signifies the method of matching images with

their physical objects, through which normative universality in art is created.

Lim’s

art combines the law of techne with the subject’s devotion. Even so, it does

not indicate that Lim is trying to do so in order to strictly abide by this

law. Rather, in the persistent manner of swaying the law of techne, she strives

to incorporate the traces of truth into the text. Through this process, a new

law of techne is created and the agent becomes ‘existent’ as both the one and

the multiple. This very process is demonstrated in International Calling

Frequency.

The

moment one participates by tuning into the International Calling Frequency, the

resulting existence can no longer be the same subject that was previously

present. Participation itself becomes a performance. This performance imitates

an event — an event that shakes the conditions of existence and thereby creates

a new agent. Lim’s work becomes art only when it is able to birth a new agent.

However, I must say that, ironically, this potential is always conditional on

the impossibility of art. Reality demolishes the possibility of art. Lim is an

artist who does not struggle against this condition, but accepts it as it is.

Herein

lies the paradox that art is impossible, but for that very reason the pursuit

of art becomes possible. Thus, sayability is a perpetual state of openness

toward the thing itself. This state itself cannot be improved upon. The only

thing one can do is pursue something within this state. In this respect, Minouk

Lim’s art is the longstanding pursuit for possibility regarding what is

impossible, performed in order to return things into language.

1.

Agamben, Giorgio, “The Thing Itself,” Substance 53 (1987), p. 25

2.

Benjamin, Walter, Reflections, Peter Demetz (trans.), (New York: Schocken,

1986), p. 325

3.

Benjamin, Walter, “The Storyteller,” Selected Writings Volume 3:

1935-1938, Edmund Jephcott, Howard Eiland, et. al. (trans.), (Cambridge MA:

Harvard UP, 2002), p. 149

4.

Badiou, Alain, Being and Event, Oliver Feltham, (trans.), (London:

Continuum, 2007), p. 192

5.

Baudelaire, Charles, The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays, Jonathan

Mayne, (trans.), (London: Phaidon, 1995), p. 9

6.

Benjamin, Walter, The Arcades Project, Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin,

(trans.), (London: Belknap, 1999), p. 417

7.

Jeong hyun, Maeng, Libidology, (Seoul: Moonji Publishing, 2009), p. 7

8.

Badiou, Alain, Being and Event, p. 198