My

grandmother taught piano. As a child I’d go to her house after school with

neighborhood friends and take turns at the piano for thirty minutes each. I was

eager to play difficult, impressive pieces, but I couldn’t bear repeating the

same études over and over. I’d play three times instead of five, twice instead

of three, and spend the remaining practice time squirming. I often ran away

from practice, so my grandmother would send my older brother to fetch me. I

grew increasingly afraid of playing the piano and lost interest in handling

instruments.

In high school, I thought playing guitar was cool. But I lacked

the resolve or passion to develop technique and was more drawn to writing than

musical expression—the endless choices and arrangements, especially of style,

seduced me. Had I known then that music was not so different, I might have had

more fun with it. As it stands, I can’t really read music beyond a basic level,

let alone play an instrument. Music became one of the things I know least and

do worst—in other words, it was long, for me, an overly professionalized

domain.

Studying

art in college and following friends to improvised-music gigs in Seoul, I felt

a kind of liberation. More precisely, it excised my inferiority complex about

music. Having experienced new criteria by which sound becomes music; music as a

method of assembling alternative systems; an aesthetic stance oriented toward

phenomenological experience—music turned from something to avoid into a matter

of choice following subjective reconceptualization, a matter of enjoyment, a

question of how far to push. Contemporary art, across domains, constantly

reconceptualizes and redefines itself in motion; one role of criticism is to

track how an artist, a work, or the systems they inhabit conceptualize and

enact art itself.

Recently,

with colleagues in band music and noise improvisation, I began a project called

“sonic fiction.” We adopted the concept of music to point toward a ghostly,

invisible world and to think through how to arrange musical elements so that

pointing succeeds. Put another way, we aim—via re-arranging elements and

reinventing the concept of music—to point to that ghostly, invisible world. At

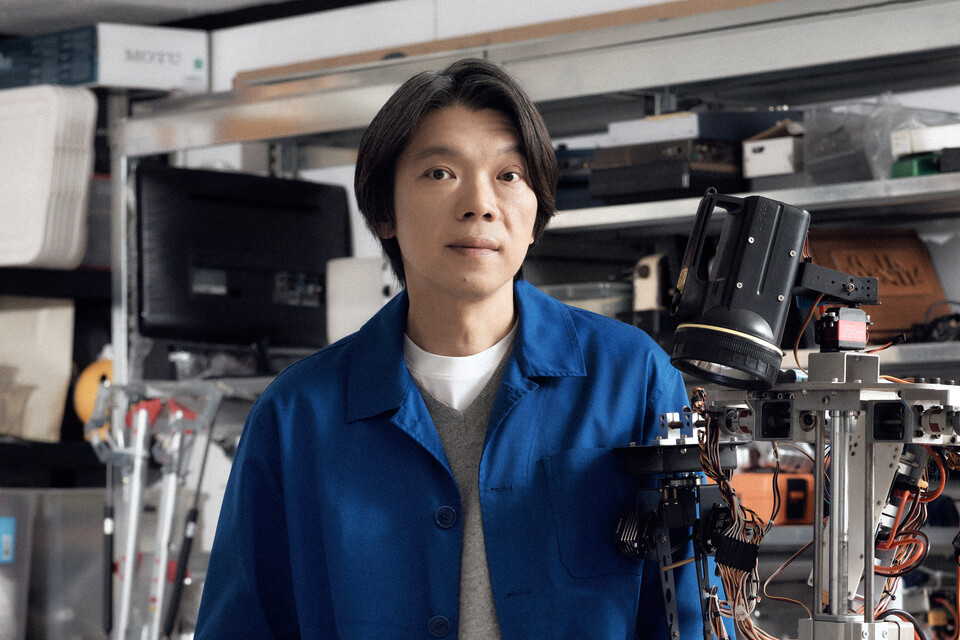

the project’s outset we invited artist Byungjun Kwon to speak about his musical

practice over the years. We wanted to know concretely what filled his artistic

practice—ever searching for new sounds, expanding the concept of music from a

starting point in band work—and what its meaning might be. Of particular

interest was his ongoing invention of new instruments.

When

we visited Kwon’s studio for a preliminary meeting, he was struggling with a

run-of-the-mill pair of consumer headphones. Those headphones were one of his

instruments-in-progress: a kind of interactive instrument that responded to

other headphones. In a large space, multiple participants wear the headphones

and move around; when they encounter others, the sounds from their respective

devices mix to create a new sound—up to three people can be mixed, he said, and

he spoke of the technical difficulties in making the instrument function

properly.

These headphones speak volumes about the nature of his instruments

and the grain of his musical practice. If you look closely at the instruments

he makes, an interesting fact emerges: he uses objects we all know and can

handle easily—like headphones. His instruments do not assume wholly new forms

or use entirely novel materials. He leverages the conventional interface

inherent to a given object (everyone knows headphones go on the head) and,

through electronic components he adds, grants that object a new interface. Thus

the listener/experiencer encounters new sonorities and a new process of

listening through a familiar object, guided by that interface.

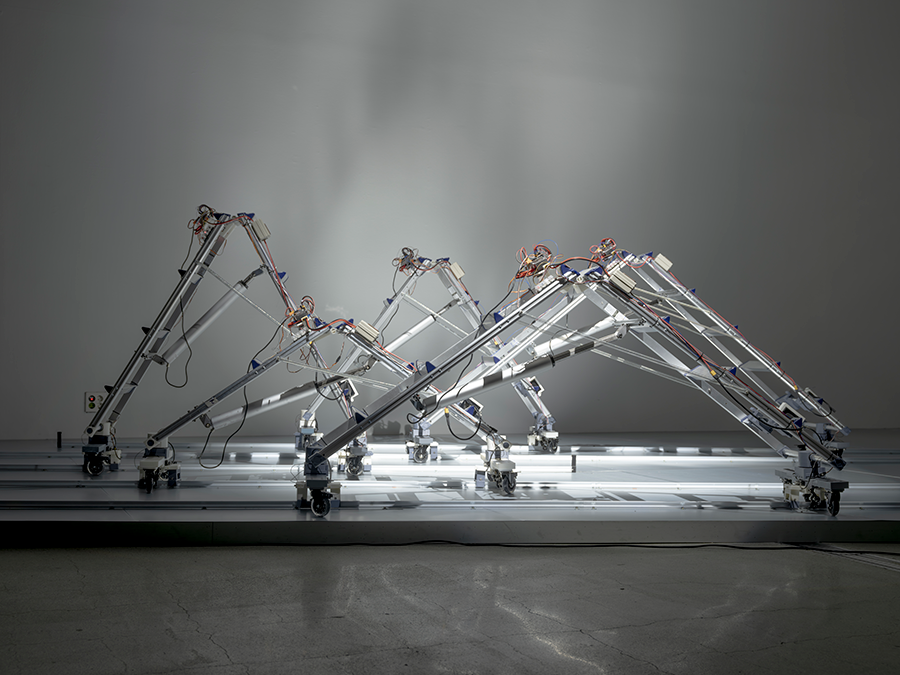

The

“hybrid piano” he recently invented and presented in several performances looks

like a piano but sounds like a string instrument. This hybrid piano retraces

the gaps in the instrument’s historical legacy—from classical performance

through Nam June Paik’s famed

smashing of pianos—revealing how the instrument has been handled in diverse

ways. In this sense, his new instruments enter a dialectical relation with

existing objects and systems.

They do not dream of a completely new,

emancipated state; rather, they take the given senses as a base and

progressively expand the concept of music—steps taken slowly. In that regard,

his music is not a materialist improvisation that, while grounded in a device’s

or object’s basic hardware, leaves all possibilities open; nor is it an

anarchic music that seeks the same hierarchy for performer and listener.

Instead, it offers performers a new interface for music—proposes, in a sense, a

program. If materialist improvisation tends toward de-ideologization, Kwon’s

instruments constitute an alternative ideology. The former tries to endlessly

reduce aesthetic experience itself; the latter mediates aesthetic experience.

A

new interface creates sounds that did not exist and reconfigures the concept of

music, while simultaneously imagining new gestures for that interface. New

gestures given to objects and machines inversely reveal the conventions long

embedded in them, emancipating performers from those conventions. Crucially,

Kwon’s instruments demand only the lightest of gestures—actions anyone can

perform, easily. This is, to some extent, his path toward a utopian

universalism of music. Thus in his work the performer’s present, embodied

gesture carries more weight than the listener’s. This is not to say he neglects

the listener. For Kwon, the listener is an element that constitutes the music

itself. His music both emancipates the performer and lays out, for the

listener, a new field: the world of sound. If image is today’s most powerful

language of meaning and the dominant sense, Kwon’s long engagement with music

is likely because, through the alternative language and sense of sound and

listening, he wishes to re-perceive and recompose the world.

Kwon

once wrote a brief essay titled “Weapons and Instruments.” It recounts his time

at STEIM, the Dutch research center for electronic instrument development,

interweaving reflections on how technologies developed for military killing

become entertainment and art with memories of large and small violences he has

seen and experienced. Weapons and instruments. Whether one is making an

instrument or a weapon; whether one should make an instrument or a weapon;

whether what he makes is an instrument or a weapon. After reading it, you

realize that making instruments is not a romantic matter for him. Rather,

instruments are an urgent, pressing demand—a way to respond to fundamentally

absurd force. The essay ends thus: “If I had the capacity, I would want to make

the most powerful thing that could erase all of this.”