A New Genre : Robot Art

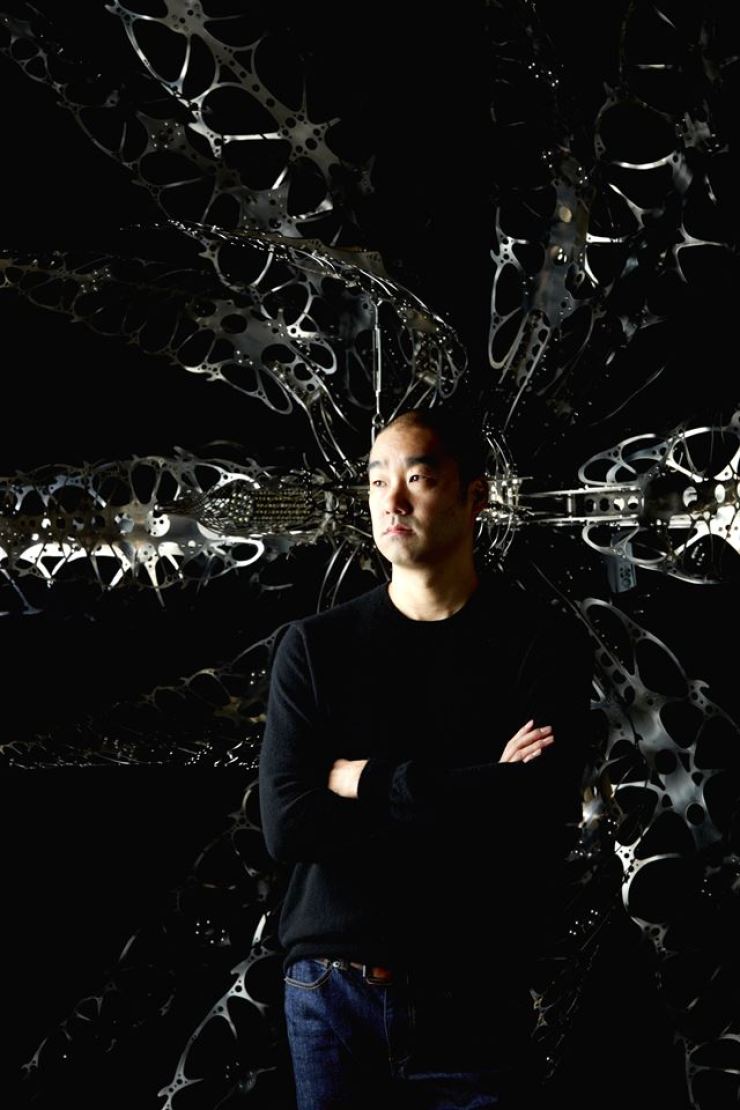

Choe's

work is a kind of progressive kinetic art, the perfect melding of artistic

imagination with technique. Advancements in technology and science has always

been a major force in taking art to the next level. The discovery of

perspective, the camera obscura, the development of new materials through

advancements in chemistry, Einstein's relativity theory, Nam June Paik's video

art, recent strides in media art -- these examples show how art has moved in

tandem with cutting-edge technology not only as in the domain of the

psychological and philosophical but also in physical terms, as material and

subject matter. Computer technology in particular has afforded artists

seemingly infinite freedom. Most of those who use it are software-oriented, but

Choe's work stakes out a new genre, one that might well be called "robot

art."It is a kind of advanced kinetic art.

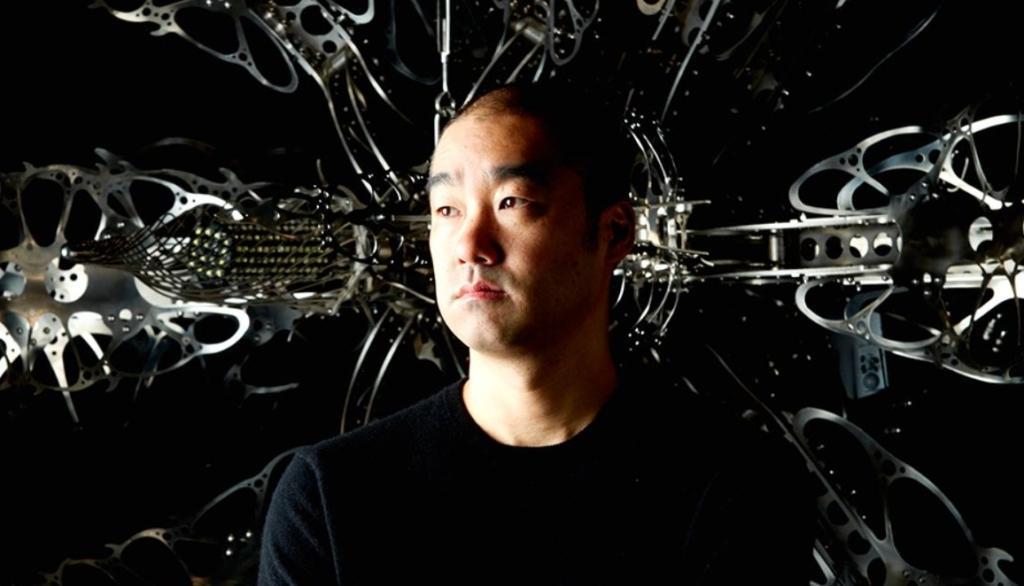

His

works sacrifice nothing of the grandeur or independence of classical sculpture.

They are free-standing "things" with fully developed storylines and

sci fi origins. To begin with, they are characterized by morphological

sophistication and beauty. Even the most simple-seeming of them is made up of

two thousand different parts, all crafted in the most meticulous detail to

embody a beautiful mechanical aesthetic. Fantasies from inside the mind become

things with a full-bodied presence, concrete sculptural objects of aesthetic

appreciation -- in short, they become another reality. In their slow, flexible

movements, they are comparable to the work of Rebecca Horn. Her mechanical

sculptures are hand-crafted machines whose operation is really very simple. The

artistry in those works, which are operated through simple mechanical control

units, and in the more advanced works of Choe U-Ram comes from the way that

lyricism thoroughly governs and mirrors technical skill. Artistic robot

sculptures come about when lyricism and technique meet in a golden ratio.

"The

mechanical organisms first arose from the boundless swelling of human

greed," Choe says. "I wanted the work to contain my own critique of

civilization, of human beings' insatiable desire." The course of

scientific development overlaps precisely with the flow of capital. No

technological advancement exists that does not generate gains. But the

technology Choe U-Ram develops is intended not to turn a profit, but to embody

an artistic idea. The slow pace of Choe's art runs counter to the fast pace of

the competition spurred on by capitalism. He is not a developer of technology,

but an artist presenting us with new ideas. Choe describes the sculpture as

"someone who expresses his feelings through shapes that do not exist in

people's heads." Today, he enjoys the status of the century's most exalted

artist and creator -- and of creator of an ecosystem.

Taming Science Through Art

Choe

U-Ram's mechanical creatures are slow and flexible in their movements. Their

motion is ill-suited to survival; any animal moving at that pace is certain to

be snapped up by a predator. Certainly, it hurts one's chances of surviving in

the jungle of capitalism, where the principles of survival of the fittest and

the strong dominating the weak operate explicitly. But no predators, no

conflict, are to be found in the ecosystem that Choe has constructed. Many

works of science fiction show a kind of proxy warfare, echoing real-world

conflicts in jaw-dropping displays of carnage and destruction. There is no war

in Choe's world.

But the creatures in it, by reflecting our world, are faithful

to the mission of art: using metaphor and imagery to express what cannot

readily be understood. Opertus Lunula Umbra, which was shown

at the 2008 Liverpool Biennial, is a behemoth of a piece, weighing in at 750

kilograms and stretching to fully 5.70 meters in length. Shaped like the

crescent of a new moon, it swam through the venue with leisurely movements of

its oarlike ribs. "On brightly moonlit nights, I would sit up watching the

sea on the docks of Liverpool and it was as though some organism was rising up

over the surface of the water," Choe says. "With this work, I was

recreating those sunken boats and machines in the waters off Liverpool."

The name of the piece means "hidden moon shadow." By giving

classical, lyrical names to his cold, mechanical beings, Choe is trying to build

a new myth where myth has been lost to civilization.

His

recent works are based in a new narrative. Arbor Deus (Tree of God)

has a mythic structure, explaining the world we live in with a critique of our

fanaticism and greed for mechanical civilization. But this mythic world is

forever in danger of being marred by human apathy and overheated desire.

Indeed, the story of the endangered Custos Cavum is fraught with tragedy. This

creature's job is to make sure the two worlds, linked by small holes, do not

become completely closed to each other. The reason they are in danger is

because memories of another world are gradually disappearing from people's

minds. And the one who brings a light of hope in this crisis is none other than

the artist: Choe U-Ram himself. "Last night," he writes, "some

Unicuses began growing out of the last remaining Custos Cavum bone in my little

yard." As long as we have artists, and as long as artists can imagine a

deeper reality within reality, the world will correct its way out of crisis.