Abstract

feelings often become material. Love becomes a glittering ring; gratitude

appears as a gift box tied with a ribbon; hatred takes the form of a torn

letter. In human society, emotions rarely remain in an immaterial state; they

convert into material forms that appear before our eyes. Intriguingly, emotions

are layered. Beneath love, gratitude, and hatred, there is always desire.

Inside the ring and the gift box, there lies the desire for a favorable reply;

inside hatred, the desire for the other’s misfortune lurks. Human society may,

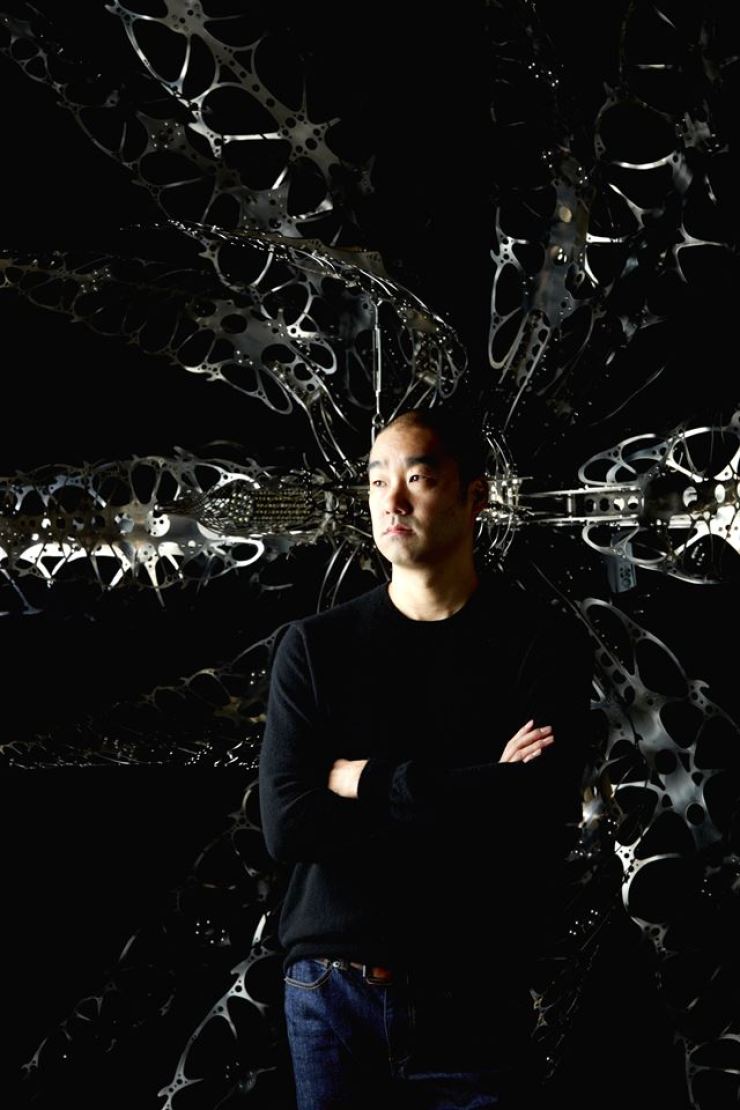

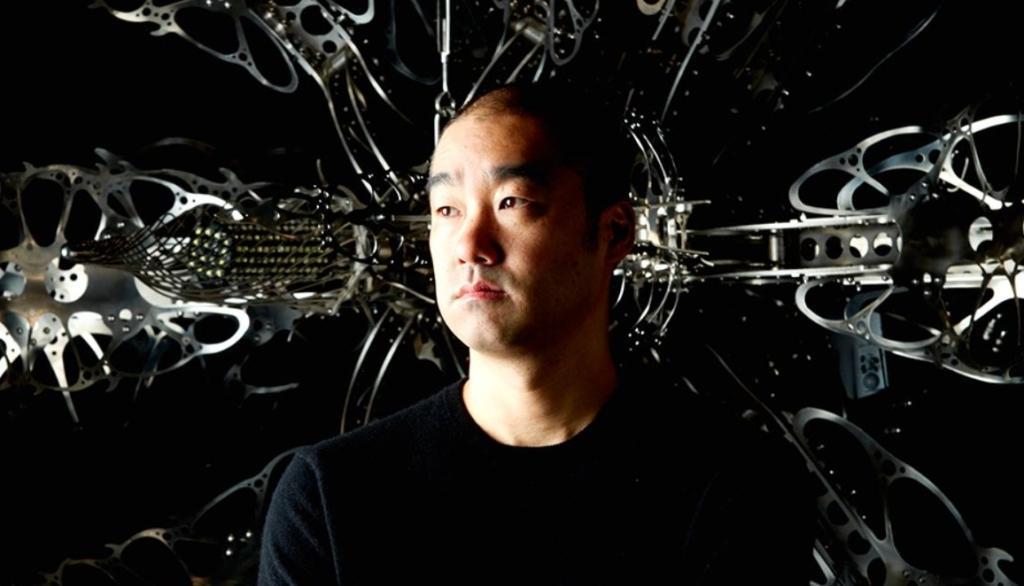

in fact, be a field in which desire constantly seethes—simply invisible. Choe

U-Ram, who creates mechanical life-forms, says his work tells “a story of

desire that, living in the interstices of human society, becomes independent

and turns into a life-form.”

Machines as the manifestation of human desire

The American philosopher of technology Lewis Mumford defined the phenomenon of

an entire society operating like a single machine according to the aims of

power and capital as the “megamachine.” This includes not only material and

technological systems but also the invisible structures created by humans. The

city is a representative example of a megamachine. Physically, urban

infrastructure and technology constitute a massive mechanical system; at the

same time, the invisible structures formed by human roles, relationships, and

organizations make the city function like a megamachine.

Born

and raised in the city, Choe discovered organic aspects in the transformations

cities undergo along with technological development. “I lived in Daechi-dong in

Seoul, and there was a new building going up outside my window. It felt like a

living thing growing taller. I realized we live in a ‘jungle of machines.’”²

“As an adult, watching cars speeding by one day, I felt as if a herd of wild

water buffalo were running. And when I lived in Gangnam during a development

boom, seeing a newly built structure rise higher with each passing day felt

like witnessing a growing organism. These experiences inspired me to combine

machine and life-form in my work.”³

Concentrated expressions of human social

traits, cities are volcanic vents of desire. Desire permeates everywhere,

turning into apartment towers, cars, and billboards that rise to touch the sky,

fill the roads, and blaze with ceaseless advertisements. In such scenes, Choe

sensed invisible life-forms. Perhaps this is why he constructs a new mechanical

ecosystem within the megamachine of the city and unfolds an imaginary world

where machines live like organisms. For example, Ultima Mudfox (2002)

is an imaginary life-form discovered at a subway construction site; Echo

Navigo (2004) is a being that feeds on the radio waves of voices

from mobile phones; and the Urbanus series (2006)

are life-forms that subsist by absorbing energy atop tall urban buildings. The

city is the ground from which the notion of organic machines springs for the

artist.

From

early on, Choe stated, “Machines exist in nature as a type of life-form.

Machines take human desire as their fundamental energy and have continued to

evolve to this day.”⁴ Seeing machines not as inanimate objects but as living

organisms, he combined them with the primal, abstract emotion of desire and

constructed a narrative of relations between machines and life. He named these

“anima machines.” The artist does not agree with labeling his work “kinetic

art,” because what matters is not merely the movement of machines but the

relationship between humans and machines and the ontology of machines.

Originally devised as tools to overcome human biological deficiencies and

limits, machines in turn drive the desire for progress and improvement,

altering human conditions and life. Machines are merely tools humans have made,

yet they also control humans and stir an even greater desire for advancement.

Machines are the manifestation of human desire. Choe’s anima machines can be

seen as living entities in which human desire infused into machines has

materialized.

A chronicle of desire–machine–life-form

From the moment Choe began presenting anima machines that combine machine and

life-form in 1998, his work drew art-world attention. It was singular at the

time and hailed as a new artistic experiment in both form and method. His solo

show 《City Energy》 at the Mori

Art Museum in Tokyo in 2006 and participation in the Liverpool Biennial in 2008

cemented his international reputation. Then 《MMCA

Hyundai Motor Series 2022: Choe U-Ram – Little Ark》 at

MMCA Seoul (2022–2023) solidified his standing in the Korean art scene.

The

three intertwined elements of “desire–machine–life-form” have run consistently

through his practice from the beginning to the present, though their relative

emphasis has shifted over time, generating varied formal iterations. His

practice can be broadly divided into four phases: an “early experimental

period” (1998–2001); a “leap of anima machines” (2002–2011); a “period of

expanded materials and forms” (2012–2021); and, from 2022 onward, a “period of

assemblies of machine-lives.”

From

1998 to 2001, during the early experimental period—including the first solo

show 《Civilization Host》

(1998) and the second 《170 Box Robots》 (2001)—a techno-dystopian aspect stands out, seemingly arising from

an intent to consciously manifest human desire in mechanical form.

From

2002 to 2011, the “leap of anima machines,” both the artist and his anima

machines became known domestically and internationally. Shedding the

techno-dystopian tint, machines appear as humanity’s companions. This phase

focuses on “machine-life,” lending realism to the works by presenting diverse

biological information as if these entities truly exist in the contemporary

world. Anima machines begin to appear as discrete forms evocative of flora and

fauna: for example, Ultima Mudfox (2002) recalls a

fish; Nox Pennatus (2005), a bird; Jet

Hiatus (2004), a shark; Una Lumino (2008),

a flower; and Ixenta Lamp (2013), a fly. Besides

feeding on human-generated radio waves or energy to survive, some exhibit

characteristics of reproduction, as in the Urbanus series.

These are traits distinct from those of inanimate machines. Choe endows his

anima machines with biological settings and, through sophisticated mechanical

design composed of motors, gears, and drive units, achieves natural motion that

breathes reality into these imaginary entities. Such settings and movements

prompt contemplation of machinic vitality. Particularly telling is that many of

his anima machines “breathe.” Breath and life are intimately linked; the very

term “anima” in anima machines comes from the

Latin for breath. (Choe often uses Latin; he assigns each anima machine a

fictional scientific name in Latin.) For instance, Opertus Lunula

Umbra (2008) begins by heaving as if exhaling a great breath

with a structure reminiscent of ribs or a crustacean shell. The

sea-lion-like Custos Cavum (2011) rapidly swells

on inhalation and then slowly subsides on exhalation, exhibiting a natural

movement akin to real breathing. This expression of respiration is a core

device that leads us to believe the machines are living beings.

Beginning

in 2012, during the “period of expanded materials and forms,” when Choe served

as a professor at the Korea National University of Arts, a major shift occurs:

from a traditional emphasis on materiality and craftsmanship to a broader focus

on thought and concept. He no longer fabricated fictional origin myths or

biological information. Previously he primarily used metal and plastic for

permanence; in this phase, he adopted varied materials and unveiled works in

new formats. He fashioned an angel out of electrical cables (Scarecrow),

or placed a plastic bag amid architectural forms (Pavilion).

The materials changed, and so did the forms—expanding from animal- and

plant-like anima machines to angels, architectural structures, a carousel,

robots, and lamps. Notably, the symbolic dimension grew stronger. Works such as

the angelic Scarecrow (2012), the contrast between

golden opulence and an everyday black plastic bag in Pavilion (2012),

the serpent eating its tail in Ouroboros (2012),

and the vortex-like spiral bloom of Una Numino (2012)

all suggest social power and human desire through their forms. Although he has

continued to present animal- and plant-like anima machines, the post-2012 works

clearly pivot toward heightened symbolism.

From

2022 onward—beginning with 《MMCA Hyundai

Motor Series 2022: Choe U-Ram – Little Ark》—we enter a

“period of assemblies of machine-lives.” This continues the prior conceptual

trajectory but with much amplified symbolism. The crucial difference is this:

whereas earlier anima machines were placed in galleries as discrete entities,

here every machine is both an autonomous unit and, at the same time, part of an

assembly that constitutes a megamachine. Round Table (2022),

in which eighteen headless strawmen support a circular top 4.5 meters in

diameter, visualizes desire for ownership. On the tabletop, strawmen strain

toward a head amid competition, while three Black Birds (2022)

glide overhead, gazing down at Round Table as if

waiting for those who fall behind. Each piece is singular, yet together they

assemble to amplify meaning.

The same is true of Little Ark (2022).

Within the twelve-meter-long ark—its black iron frame patched with

white-painted discarded paper boxes and lined with thirty-five pairs of

oars—are Lighthouse, acting as a panopticon; Two

Captains pointing in opposite directions; and the space

telescope James Webb. An Anchor—whether

connected to or broken from the ark is unclear—juts from the wall beside it,

while a drooping Angel, a ship’s figurehead, hangs from

the ceiling. At one prow lies Infinite Space, showing

endlessly amplifying space; at the other, the video work Exit in

which doors open without end (Little Ark makes it

impossible to tell which side is the prow). The ark, its internal components,

and the surrounding works each possess meaning as singular entities; as an

assembly, they cohere into a single megamachine. This method of assembling

makes even more explicit that “the ark is ultimately a lump of empty desire

that cannot carry anything.”

Through

Choe U-Ram, desire bores through the society we inhabit and appears before us

as mechanical life-forms.

The

desire he reveals is a golden architectural structure,

a serpent devouring its own tail,

strawmen ceaselessly striving to seize a head,

black

birds lying in wait for stragglers,

an ark with no front or back,

two captains pointing different ways, and James Webb.

Desire

constructs infinitely amplifying spaces

and exits from which there is no escape.

Desire

is by no means invisible.