The

subject matter of Rho Jae Oonis the fundamental system of human perception and

cognition. We gather and organize information through ‘what we see’ in form of

image or text to construct knowledge, on which we make a value system and its

corresponding ‘view’ of value. The artist is anxious about our system (and

ways) of thinking that could be easily cooked up by all the visual images.

His critical consciousness is rooted in the understanding that ‘what we see’

inculcates us with a certain way ‘how to see.’ If you do not follow the ‘common

way of seeing,’ you are not able to share the ‘common sense’ and understand

common knowledge, falling behind and even alienated from your communities.

Whether you are on/off line, in public/private spheres, or in rural/urban

areas, you are always under the same constraint. Especially in Korea, which is

densely populated and changing fast under the socio-politically complicated

situation, the power of the visual that an individual feels is far more

substantial, ungraspable, and omnipresent. Our eyes are enclosed with various

mediated knowledge, such as the endless parade of TV drama from morning till

evening, the deluge of news articles updated real time on the Internet portal

sites, the visually clamorous personal blogs, and the SMS messages loaded with

unexpected information, all of which dominate the common sense and penetrate

our thoughts. Even to the masses having little thoughts, the ‘eyes’ are an

intense battlefield between the individual and the uniform, common sense.

In the solo show Skin of South Korea in 2004, Roh already addressed the problem

that images transferred and even determined the information and knowledge that

we shared. He selected highly influential images in taking shape of the common

view of value, from numerous image data in the Internet, and transformed them

into a series of signs to create a ‘skin’ of Korea. However, 1) the medium and

method of the skin were too avant-garde to the serious art people in Korea; 2)

The icons of the skin were visually too attractive; and 3) The contents of the

skin were too appropriate to the alternative politics demanded in the stiff

socio-political atmosphere in Korean art. So the exhibition happened to make

several ‘filters’ through which Roh’s works could not be fully understood in

art scene.

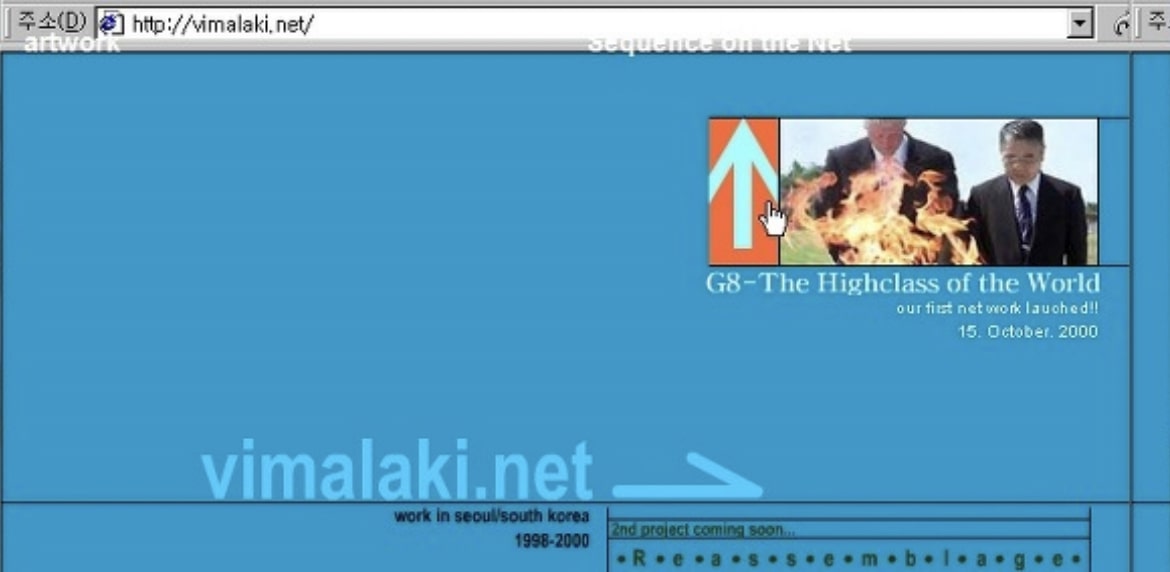

First, we have a filter that amplifies the importance of the technique. Roh

usually collects, processes (with ‘Photoshop’ or ‘Premier’), and redistributes

various still and moving images on the Internet. As electronic medium is no

more a necessary and sufficient condition of media art, his works do not have

the prestige of ‘digital art.’ However, digital medium is still addressed in

political, economic, and institutional contexts as a subversive,

anti-capitalist, and open form against the myth of originality and authorship

and the art system (PARK Chan-kyong, “Analogue aesthetics of digital art”). This

sort of discussion on format is definitely reasonable, but gives the wrong

impression that his works are meaningful only in terms of its medium and

technique (or the artist is a medium-specific otaku[オタク]). In reality, he makes use of various mediums including 2d

graphics, video, object, photography, painting, text, poster, installation, and

even out-door sculpture. He does not merely proliferate the skin works between

the Internet and the computer, but also experiments and expands the concept of

skin and its results by photographing, writing, making a spatial structure with

skin patterns, flying an object, etc. Trained as painter, he has skillful hands

and even an experience of making a quite wild video. The World Wide Web is for him

merely a powerful occupant of the ‘eyes’ in everyday and a working field easy

and economical to intervene. It is a realistic and cool choice of the X

generation, not of a naïve amateur. In this context, he gathers and edits the

raw materials found in thousands of sites and hundreds of films, processing

numerous pixels with the traditional craftsmanship. In consequence, the recent

work 〈Bite the Bullet!〉(2008)

is not a fragmentary skin but a ‘web publishing,’ which consists of 12

‘chapters’ and 10 scenes of edited moving images. Here the artist pays

attention to the occupation of the ‘ears’ as well as of the ‘eyes,’ juxtaposing

various sound effects, movie quotes, and recordings with his characteristic

visual composition. The relation between sound and image also varies: the

soundtrack supplementing the visual (ch.5: The Dog Fight); the ambient sound

leading the visual (ch.9: In a Shattered Mirror); the para-textual sound

contrasting with the visual (ch.10: Blind Game, #2: You can’t handle the

truth); and the sound without the visual (ch.4: General). This work suggests

that the artist would expand his exploration from the visible to the audible.

Second, we have two filters that emphasize the iconic images Roh creates, one

for their meanings and the other for their operational strategy in which the

artist’s attitude is revealed. These frameworks, each corresponding to 2) and

3), produce two opposite prejudices against him. Based on 2), it is said that

‘the artists like Roh are a fold-maker who scans and visualizes the symptomatic

surface of contemporary society in form of decoration’(KIM Jang-un, “Baroque

Scenario”). Based on 3), on the other hand, it is said that Roh mainly edits

and translates the images of ‘political catastrophe’ found in hyper-narratives

on the Internet to ‘visualize his own opinion and establish a peculiar order

and meanings’(MOON Young-min, “Jae OonRoh: artistic intervention in

hyper-narratives”). The perspective of 2), expressed in a review on the

artist’s first solo show in 2004, is no more persuasive in considering his

later works. But it is still fossilized in the filter through which his works

is seen as similar to the prototype design of the Russian Avant-garde. Against

this stereotyping, the other perspective appears that his works are basically

‘caricaturing at a critical distance’ but shows ‘a productive possibility of

mutual contamination between the aesthetic and the political’ through careful

selecting and subjective editing of political symptoms. In this perspective,

given that the artistic intervention is always subjective in principle, the

essential merit of Roh is his rather new form and stance to deal with political

matters. While this filter discloses that he is not merely an internet kid in

virtual reality but a socio-politically engaged artist with sharp sensitivity

to symptomatic phenomena in the un-realistic reality of Korea, it is not enough

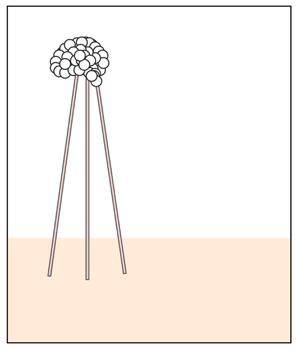

to explain the 〈Magenta Ball〉

floated in the sky of Anyang in 2008, or the narration that ‘I saw a dead man

won victory in a fight beyond the sky island far away’ in the interface

installation 〈Chamber 31〉.

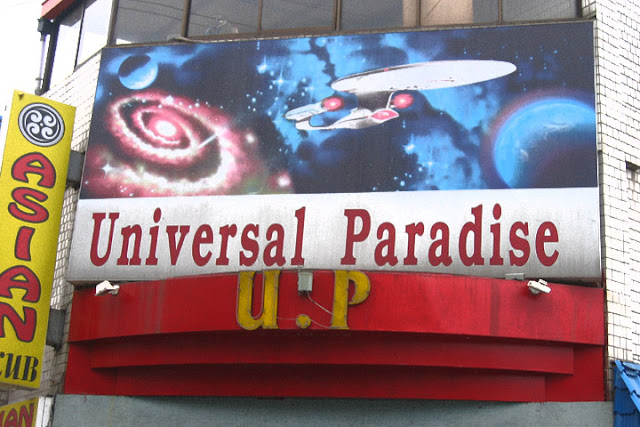

Against the danger of excessive politicization, Roh clearly demonstrates his

critical consciousness in recent works such as the Magenta project and 〈Bite the Bullet!〉 filmed in Dongdoochun. He

sees our ontological situation and perception/cognition framework is not merely

‘political’ but rather ‘cinematic.’ His ‘taste’ is not the only reason why he

kept the skin works amplifying the cinematic reality and its virtuality based

on science-fictional imagination for the future against the stiff and simple

frameworks of politics in Korea. However, the implosive skin toward another

virtuality is no more valid in such a place like Dongdoochun, where frameworks

and its implosive alternatives already coexist for more than a half-century. In

fact, the implosive and alternative frameworks are invented and realized by

colossal capital, military institutions, and space techno-science, invading our

imagination, perception, and cognition toward the future. So he does not

comment on the influential icons through the skin works any more, but

reconstructs the structure of narrative that forces us a certain way of seeing.

His new strategy of ‘universal cinema’ is to analyze the narrative structure by

pixels, to edit and translate them into a ‘universal’ archetype of narrative.

This method, first attempted in 〈Bite the Bullet!〉, is another effort of the artist to barricade our perception and

cognition to save the imagination for the future(KIM Hee-jin, “A conversation

with Rho Jae Oonand the artist’s note”).