In Rho Jae Oon’s work, we

encounter a linkage of history to the visual, one that involves a disruption of

the ways in which history has been associated with perspectival depth, as

receding into the past, moving into the present, projecting itself into the

future. Instead, the historical emerges as a set of mediated surfaces, each

co-existing with the other. In the Aegibong Project, for example, Rho

dismantles a totalizing progression or even dialectic, invoking not a movement

from the narrative of faithful mistress (remaining in the name “Aegibong”

territorializing this space) and foreign invasion (the Ching incursion of 1636)

toward the ravages of the Korean War (1950-53) and national division and into a

developmentalist future (the images of factory construction we encounter), but

a memory of surfaces. The Aegibong Project unpacks the ways in which history

itself is bound up with the visual order, particularly via its summoning of a

perspectival subject that is to stand before it and watch it recede, proceed,

project in time and space. It is not a visual history, then, that we encounter

in the Aegibong Project or in Rho’s other works, but a display of the ways in

which history, and the violence that accompanies it, proceeds via the relation

between history and visuality.

If Rho’s works, then, turn to bricolage to interrupt a naturalized way of

seeing, this redistribution of images (which includes videos, film stills,

satellite photos, graphics, video, object, photography, paintings, posters,

installations) does not move to a celebration of the aleatory as such; instead,

contingency emerges as that which simultaneously enables both violence/war and

the subversive, open-ended gesture that would oppose it. As we see in Bite the

Bullet!, the close relation Paul Virilio and others have demonstrated between

the scopic regime of the cinema and the technics of mobility and targeting that

inform modern warfare (and its accompanying disciplining structures) exists

precisely to eradicate the contingent by way of an all-seeing gaze. If, under

this visual regime, “to see is to destroy” we can add an object to the phrase:

“to see is to destroy the contingent.” Rho’s Bite the Bullet! allows us to

begin to understand the ways in which the anxiety of the contingent sets the scopic

regime of war and cinema into motion in the first place.

Bite the Bullet! has no interest in erasing the history of U.S. filmic

imaginings of the “Korean War.” Nor does it seek to reverse the

targeter/targeted relation that underpins the U.S. combat film, although it

does, on one level, produce this effect, showing us how the image of the

targeter—the combat pilot, or scopic regime that objectifies “Korea”—always

contains, at the moment of its production/projection, the possibility that the

gaze can turn back on itself, that the perspectival subject, the subject of

history who operates from a distance, the releaser of bombs, is, himself,

always already the object of a gaze. If this was the case in U.S. movie

theaters in the 1950s when films like The Bridges of Toko-ri were made, at

stake is an interruption of the ways in which an audience identifies with the

filmic image of the bomber-subject, sees as he sees rather than sees how he

sees. But to reverse the order, to target the targeter does little to dismantle

the history informing this scopic regime of violence, the identification of a

film spectatorship with a totalizing way of seeing, one rehearsed in George

Lucas’s Star Wars, frequently invoked by Rho, where the bombing runs leading to

the destruction of the Death Star draw considerably from the famous bombing

sequences in The Bridges of Toko-ri, Star Wars becoming an extension of the

virtuality that, for a U.S. spectatorship, was the Korean War.

Rho’s Bite the Bullet! shows us how the image of the bomber and the bomber’s

gaze upon his target is unstable, anxious from the beginning. To be sure, to

identify with this gaze is to sanction its violence; in the same way, to

reverse the gaze, to hold it in one’s sites as object is to acquiescence to its

code. Rho’s bricolage refuses the separation of subject from object, locating

the political, violence, and history, in the structural instability of the gaze

itself. We cannot separate ourselves out from the act of destruction, distance

ourselves from the target or the prosthetics of the machinery that enables

violence while attempting to lessen the trauma of inflicting it. The viewer of

Rho’s work must do something more that “see” as if a pure, disembodied seeing

can be had from on high (in a plane or in front of a screen). Instead, we

encounter a tactile vision, a reintroduction of the body as a relation of one

surface to another (thus Rho’s concern with skins in his recent work): we come

into contact with the ways in which seeing is material, touching that which the

scopic regime of violence would separate out as other: we “bite the bullet.”

In “Identification of Woman” and “Baudrillard in Seoul,” Rho introduces the

pixel to what, in different ways, Martin Heidegger, Mary Anne Doane, and Susan

Stewart, have noted defines the visual modern: the simultaneous desire for an

overwhelming visual presence and a graspable miniaturization, something akin to

the relation between close-up and extreme long shot. In Rho’s work, we move

ever closer, zooming in from medium shot to close-up, with the image

disintegrating to pixels. Here, we have an interruption of a gendered gaze and

what Laura Mulvey has called visual pleasure. The move beyond the close-up to

the pixel, to the “closest up,” disallows a look upon by the subject and a

resistive “look back” by the object. The concern here is elsewhere: the move is

to the virtual building blocks of the digital image, the pixel, precisely to

encounter its virtuality as a form of materiality, the material that

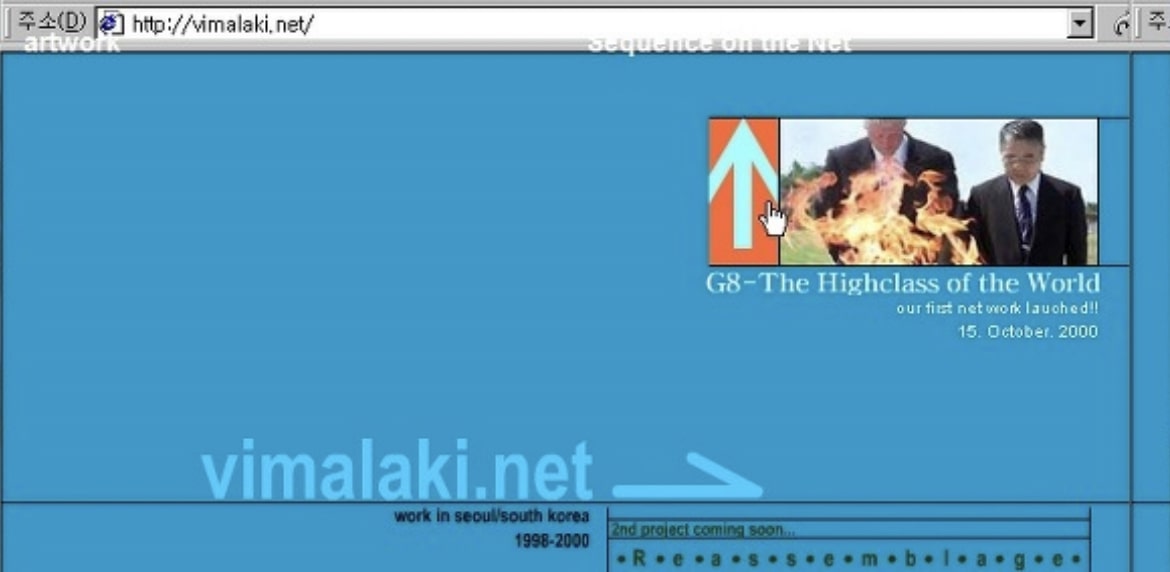

constitutes the images circulated globally via the World Wide Web and all of

the changing formats/technologies that constitute its reach. Like science

fiction (frequently alluded to in Rho’s work), the World Wide Web is real.

That the pixels, uniform in size and progressively blurring as we move closer,

constitute images associated with notions of desirability as we move away

allows us to see how hierarchy is created visually, how clarity and focus are

embedded in a history of value inextricably linked to a way of seeing via

naturalized codes. Rho’s deploying of a “universal cinema” emerges here neither

as the elimination of the particular nor as the privileging of the universal in

relation to the particular, a gesture, as Etienne Balibar has shown, that

reveals how the notion of the universal depends on the particular as its other.

In my view, Rho is using the notion of the universal in a very different way,

much more in terms of a web of interrelated singularities that can constitute

open-ended, non-hierarchical relations only by remembering how these

singularities can be erased (like the pixels that disappear as an image forms).

Rho’s interventions allow us to see how “Korea” is one site among many,

embedded in a global circulation of images which allows for the production of

multiple histories, as well as oppositions (for example, the north/south

division of the Korean peninsula’s geospace, one which informs much of Rho’s

work). At the same time, Rho offers us a history of this circulation, one that

implicates the 1950s in a scopic regime that continues the Korean War globally

in different forms, fully capable of producing violence. Here, I think, lies

the signal importance of Rho’s project to dismantle this regime via a

“universal cinema,” one that includes Korea but moves, in ways that expose the

anxiety marking global militarization and its accompanying ways of seeing, well

beyond the notion of “national borders.”