Sejin Park

is an artist who closely links the material properties of her media to the

content of her painting. Employing oil, acrylic, fabric, paper, glue, and even

natural substances such as cherry or rose juice, her practice can be read as an

experiment that revives the vitality of color and texture. Run

and Run Again! infuses paper with pigment made by mixing cherry

juice and glue, transforming the organic hues of nature into the breathing

rhythm of a landscape.

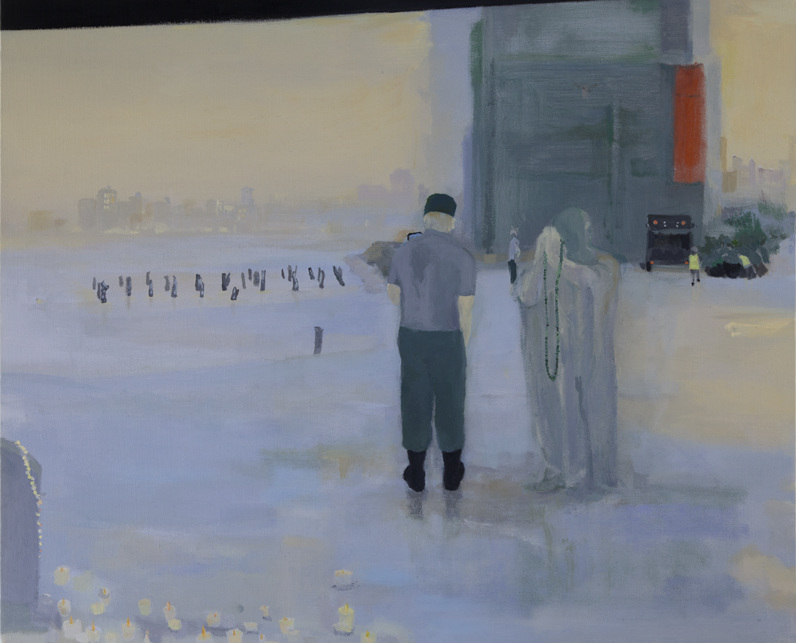

In her

compositions, the continuity between the foreground and the background forms an

essential structure. In works such as Old Morning(2007)

and Crying Soldier(2007), the precisely rendered

foreground and the faint, dissolving background reflect one another, erasing

boundaries. This “painting of overlap” is an attempt to layer traces of time

upon the material surface, visualizing what the artist calls “the traces left

by the absence of time.”

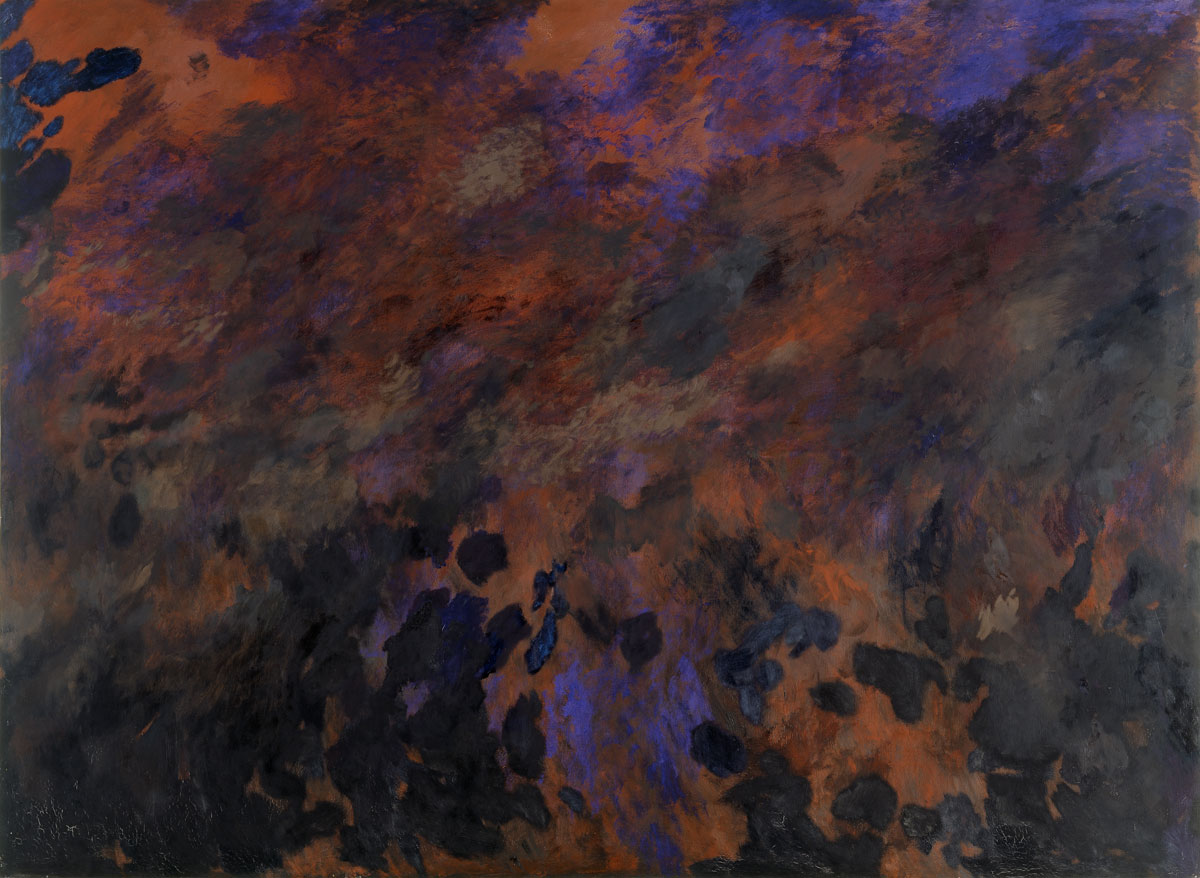

In works

such as Night, the most notable feature is the

materiality of the brushstroke and impasto. Outlines disappear, the texture of

brush marks becomes prominent, and the surface changes color according to light

conditions—devices that visually articulate the uncertainty of perception

within darkness. Conversely, in later works such

as Wall, stains, mold, and marks of rainwater on

concrete surfaces are reinterpreted as painterly expressions of nature itself.

Since the

2000s, her work has been marked by a persistent observation of the colors and

textures of local Korean nature—its skies, stones, and mountains. From the

2010s onward, the resonance between memory, consciousness, and emotion became

stronger, signaling a shift from “visible landscapes” to “invisible relations.”

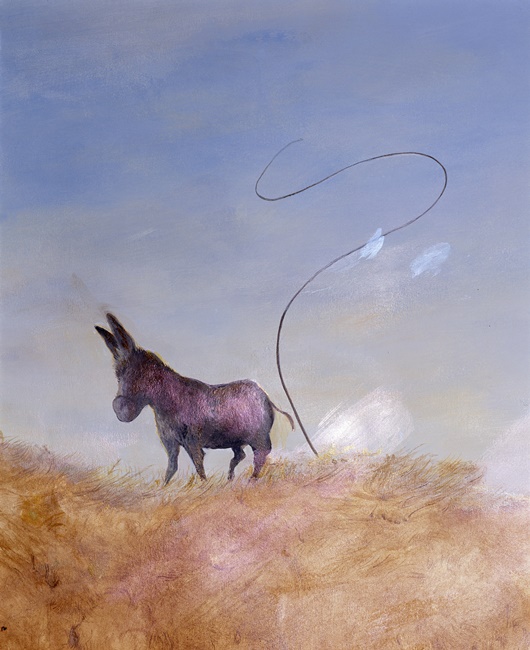

While the memory of Panmunjom in Landscape

1993-2002 invited an imagination of the unreachable other, the

recent hillside series depicts landscapes where the lives of self and other are

reflected and connected. Ultimately, Park’s landscapes are not records of the

external world but projections of inner perception—painting as the geography of

emotion.