The

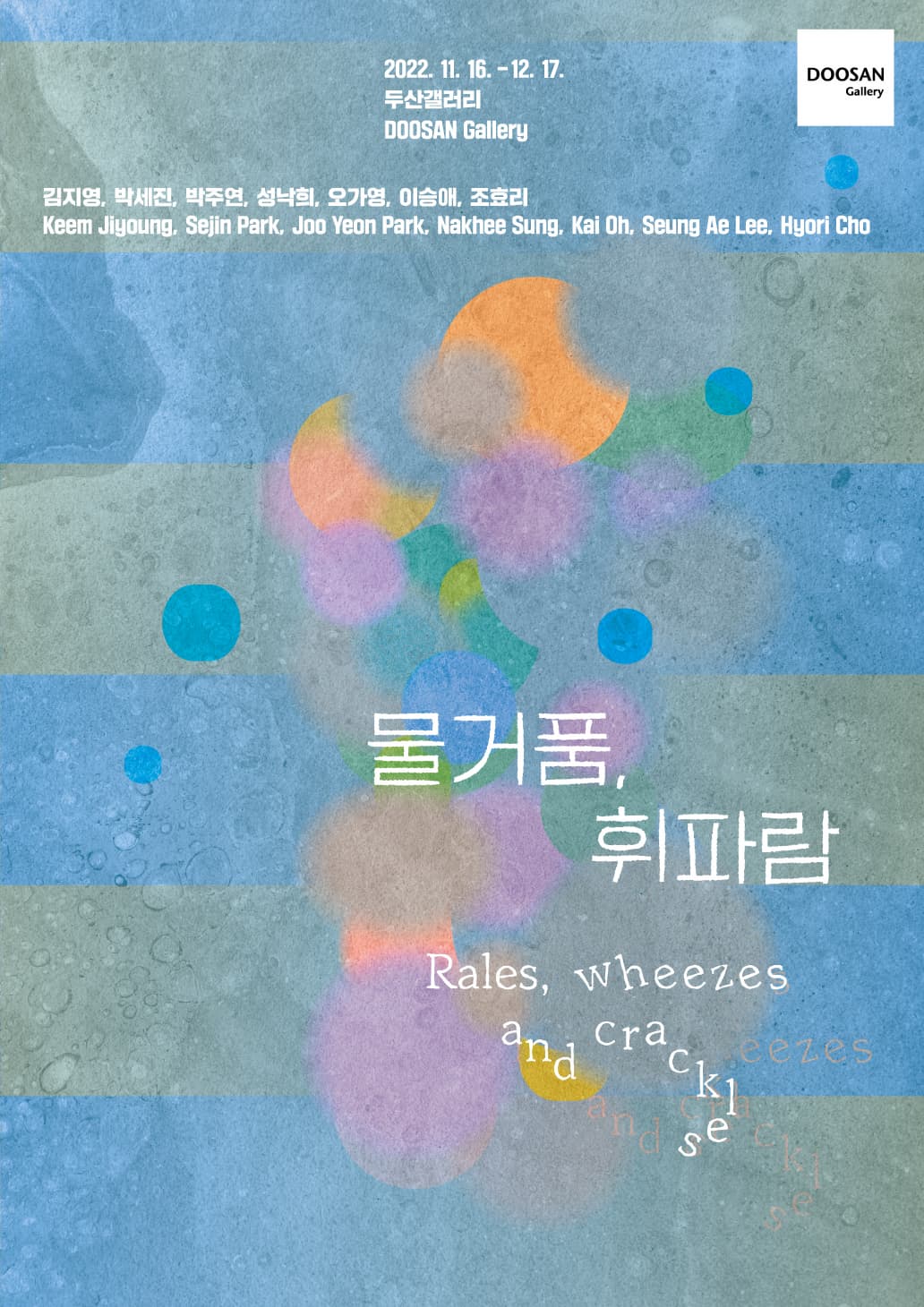

paintings of Nakhee Sung (b. 1971) are renowned for their exploration of an

infinitely proliferating world of abstract forms. In each work, masses of color

that transform into dots, lines, and planes emerge, dividing and occupying the

canvas. Each elemental unit seems governed by an internal genetic protocol.

Her

paintings can be appreciated much like pop music. To use an analogy: the first

encounter calls for attention to the overall impression rather than analytical

thought; the second follows the melody of the vocals; the third focuses on the

guitar track; the fourth isolates the keyboard; the fifth attends to the bass

line; and the sixth to percussion. Finally, one begins to discern when and how

each channel attaches and detaches from the structure, and an understanding of

the overall formal composition of the sound gradually takes shape.

The

new works unveiled in her 7th solo exhibition 《Translation》 bear a peculiar quality. Titled

Entrance, Leap, Settlement, Condensation, Outflow, Whirl, Resonance,

Reverberation, and Tone, they serve as diagrams

illustrating the contrapuntal foundation of Sung’s abstract painting practice—a

microcosm of her painterly world that now explains itself through painting once

again.

The

artist sought to create “viewer-centered paintings.” Hence the title 《Translation》: to make her works more easily

legible and interpretable, she presented them frontally, facing the viewer. “In

the end, the paintings became remarkably flat,” she says.

This

new phase of painting, begun in 2002, seems now to reach the close of its first

act. The color-shapes—resembling primitive organisms—once born on paper,

expanded restlessly across gallery walls and canvases alike. Now, they have

evolved to the stage of self-reflection and self-explanation.

One

key viewing point is gravity—both literal and pictorial. There is the real

force of gravity, and then there is the gravitational (or magnetic) pull that

operates virtually within the picture plane. Beyond the traces of paint that

flow downward under real gravity, we can speculate about the multiple

gravitational forces that acted on the work during its making. Through this,

one experiences the painting as if it were rotating, lying flat on the ground,

and then rising again on the wall to face “me”—a mysterious and intimate

encounter between viewer and work.